Territory Music: Local Bands

In the last thirty years, historians have given an important place to “territory bands” in the development of jazz during the late 1920s and 1930s. “Territory bands” were regional pop music orchestras between the two World Wars. These groups, like Troy Floyd in Texas or the Blue Devils in Oklahoma and Missouri, performed far outside the major music industry centers, which were concentrated in the U.S.’s largest, most commercially developed cities: New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Gaining fame corresponded to living in one of these music centers and the most famous bands of this period—Duke Ellington , Benny Goodman , Cab Calloway , or Tommy Dorsey —based themselves in these locations.

But there were a vast number of musicians and musical groups who performed in places far from these metropolises—in Omaha, Dallas, Kansas City, and countless other small and medium size cities. These bands were in the “territories.” Because of their remoteness, territory bands remained largely peripheral to the national music industry during their lifetimes. Most had strictly local or regional audiences. Some recorded in mobile location studios in San Antonio or St. Louis, but many never recorded at all. Their music has only survived in stories and memories from decades later, often told by other musicians. The territory bands that did become stars, like Count Basie or Jimmie Lunceford , did so by leaving home and moving to New York.

Despite their relative obscurity, composer and historian Gunther Schuller has argued that territory bands were key to the history of jazz. As the music industry consolidated during the Depression, they represented unique variations of the jazz orchestra, offering a contrast to the highly-arranged and controlled styles of mainstream dance and Swing bands like Guy Lombardo and Glenn Miller. In addition to this, Schuller contends that

Territory bands were constantly on the move. They had a home base and, if lucky, would perform extended residencies at an elite hotel there. In Texas, the major hotels for dance bands were the Adolphus in Dallas, the Galvez in Galveston, the Rice in Houston, and the Gunter, Plaza, and Saint Anthony in San Antonio. From these cities, they would travel from town to town, performing in any place they could: dance halls, restaurants, taverns, gyms, or clubs. Traveling in Jim Crow America was difficult, not particularly lucrative, and, for African Americans, dangerous and burdensome.

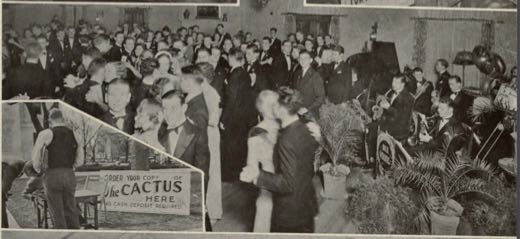

Dance and big band music in the 1930s was deeply tied to organizational life in Austin. The main venues in Austin for territory bands were ballrooms in the 1930s were dominated by students and clubs at the Universities: Gregory Gym , the Texas Union , the Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs , the Austin Country Club , the Driskill Hotel , the Stephen F. Austin Hotel , the Samuel Huston College Gym, or Beard Hall on the Tillotson campus. Other organizations, like the Ben Hur Shriners or the Travis County American Legion, also held dances for the members at the Driskill, the Shrine Temple building, or the Legion Hall. In the mid-1930s, the Junior Club of the Degree of Honor, a mutual aid society, held dances with the Kayo Cloud Orchestra at Dessau Hall on the outskirts of town.

There were other venues that had a wider clientele, however. Major touring acts like Cab Calloway or Don Redman’s orchestras also played in revues at the Paramount Theater on Congress Ave, close to the Texas Capital. The Royal Auditorium /Cotton Club on 11th Street often advertised and catered to UT and Samuel Huston students, but it served as the main dance hall for the wider black community. Starting in the late 1930, dinner clubs and venues like the Avalon and the Tower began to host dances and revue shows with big bands. For the first handful of years they focused on attracting the main clientele for sweet and swing music: white students. This changed in the 1940s, however, as upturn of the war economy gave more people expendable income. More and more clubs opened up by the mid-1940s and they hosted music—often Western Swing—that appealed to the taste of white working class audiences.

In the 1930s and early 1940s, Austin was not a major residence for the most significant territory orchestras in the state, although it did have bands that performed outside its city limits. Austin’s bands did have one unique characteristic that set it apart from most other Texas territory groups, however: its orchestras and audiences were deeply tied to the city’s universities. Consequently, its dance band musicians had very high degrees of formal Western music training. Most territory bands during the period, on the other hand, had informal educations and learned to play by ear.

Two Trajectories: The Gardner Brothers and Ben Young

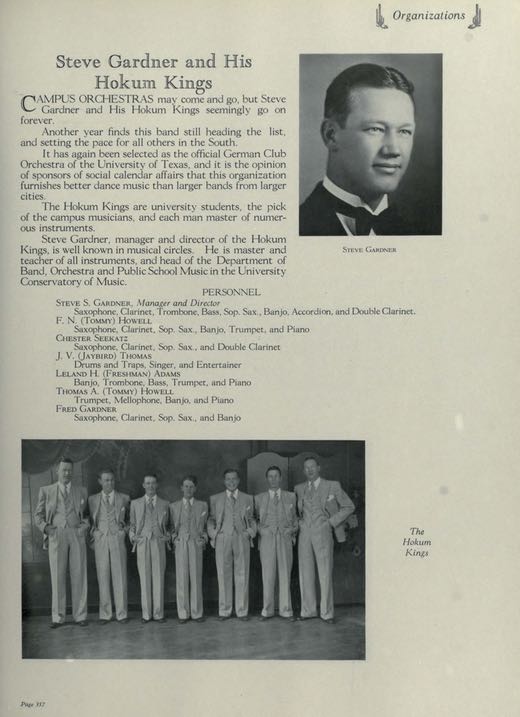

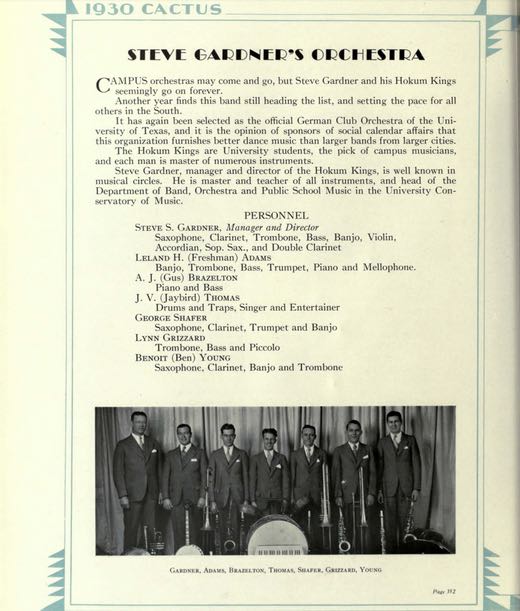

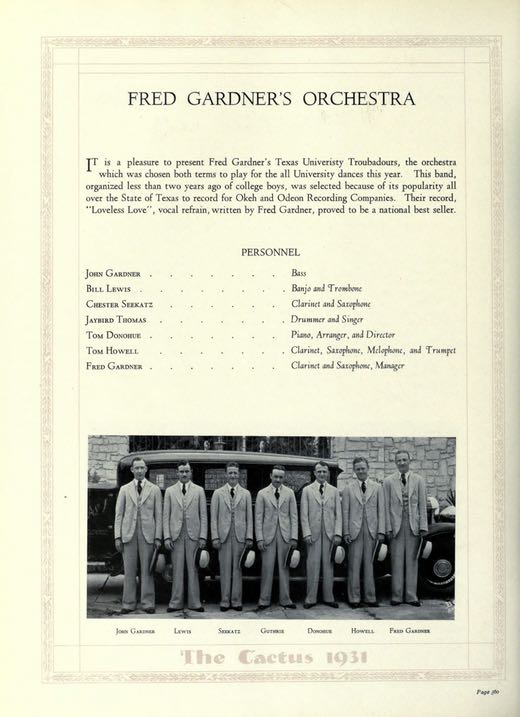

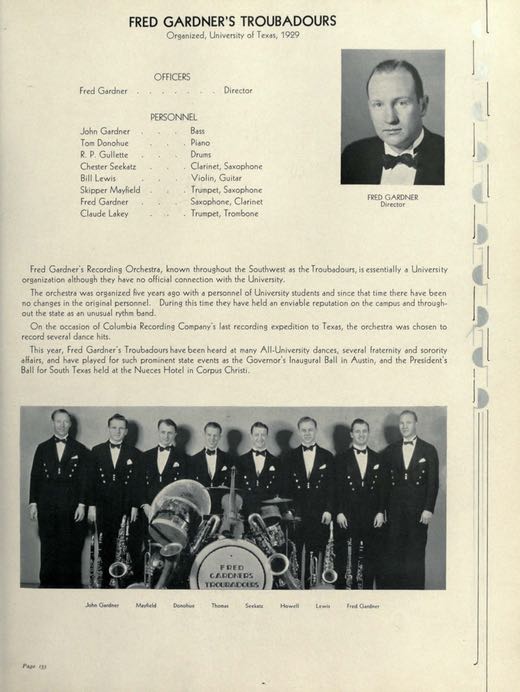

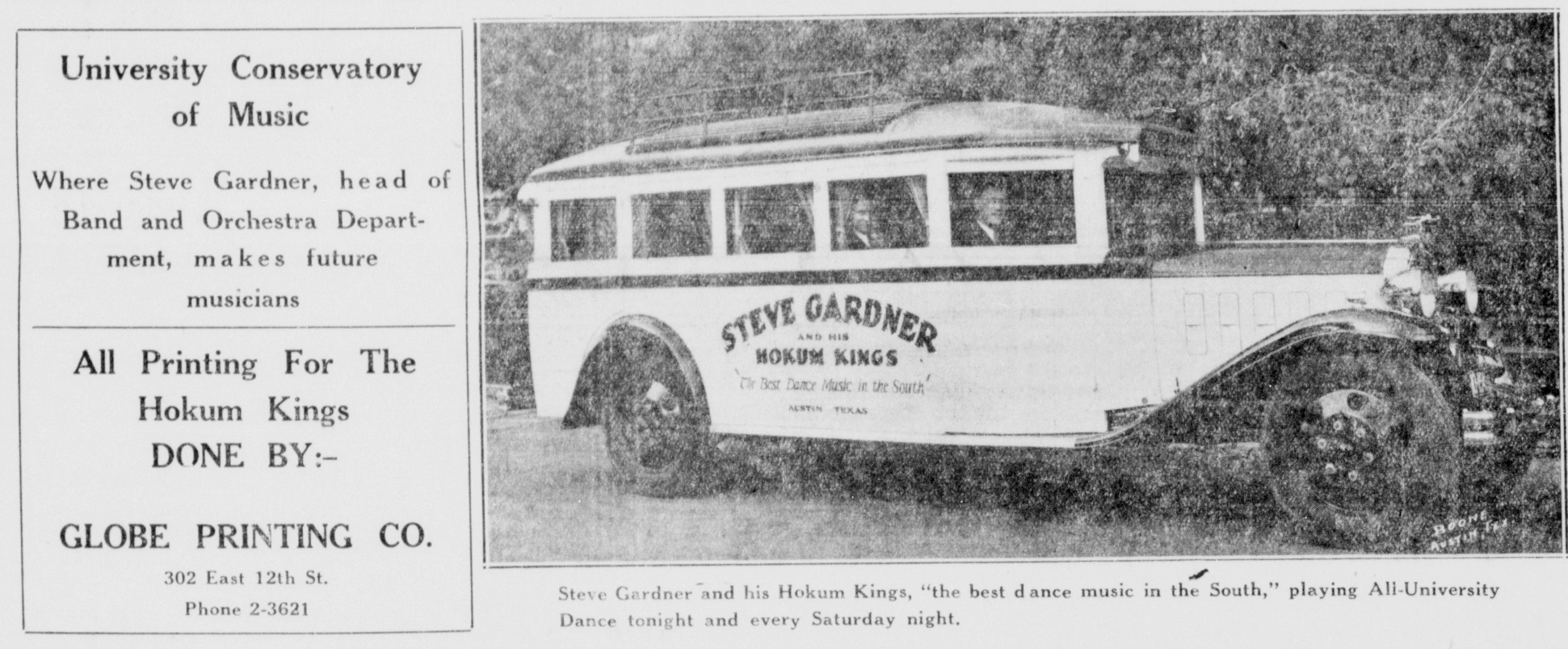

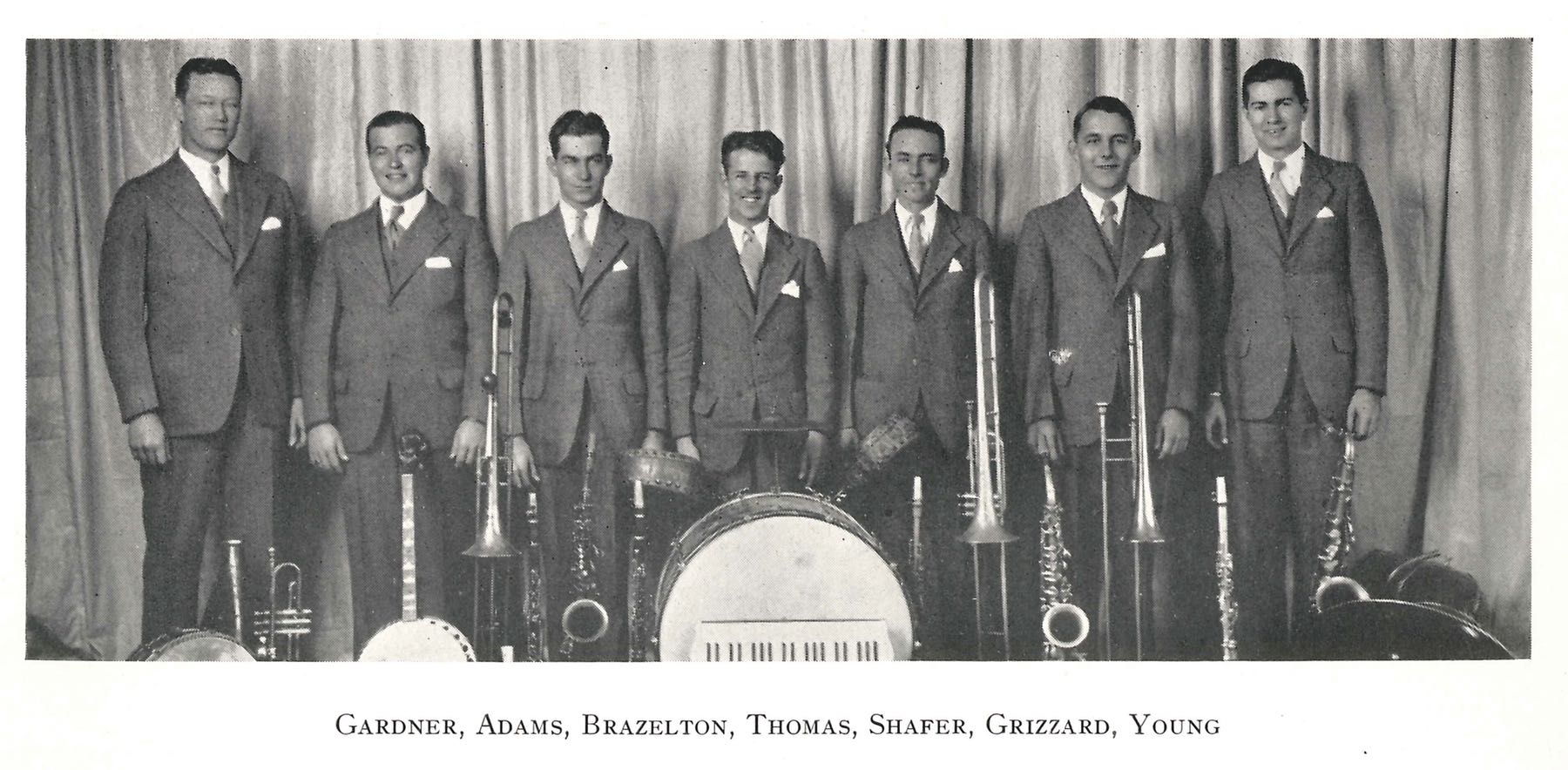

Although not one of the premier cities for orchestras, there was consistently a large number of orchestras in Austin. Most of the dance bands in Austin were formed in the 1930s and 1940s; Steve and Fred Gardner , however, had been key parts of the university jazz scene since 1920. For their first few years, they played in early jazz ensembles like the “Howell and Gardner Band-its” and “the Texans.” organized in 1924, originally included both brothers. The orchestra was born out of UT: selected as the “official German Club Orchestra of the University of Texas” more than once, the band was composed of all university students. Steve, its leader, was also a music teacher at UT and the head of the Department of Band, Orchestra and Public School Music at the university’s conservatory (before it had a College of Music).

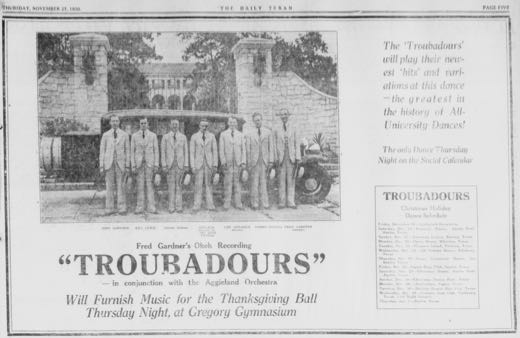

Fred, a saxophonist, left the group and started his own “Texas University Troubadours” band in 1929. It’s unclear if the split was congenial or part of an altercation. Whether friendly or not, UT students had a chance to compare the bands in the early 1930s, since the brothers’ orchestra played a number of “battle dance” competitions in Gregory gym. Fred’s Troubadours became the official orchestra for UT in 1931 and 1932. In 1935, as both their popularity waned and new orchestras in town rose, they often merged their groups and performed as a “combined orchestra.”

Steve Gardner and His Hokum Kings, regional touring, 1930

This interactive map feature requires JavaScript to function.

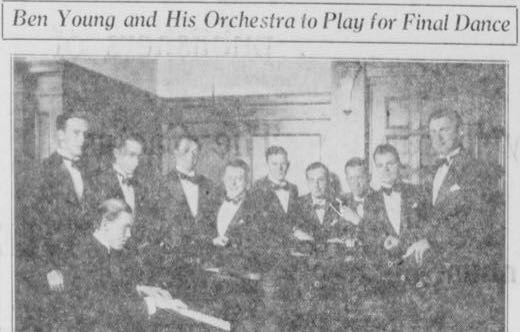

After a few years playing at the Union and Gregory, Young attempted to transform his group from a local band to a nationally-known ensemble. For ambitious bandleaders, this meant leaving Central Texas, since it was near impossible to rise in the music industry from Austin in the 1930s. So, in 1937, the Young band left their local base in Texas and became a roving territory band, performing all over the country. Young’s reputation seemed to be growing when his talent was ransacked by a more established competitor. While playing a month-long gig at a hotel in Detroit, the drummer Gene Krupa heard the orchestra and hired away two of Young’s best musicians.

The Gardners and Young were but two of the many UT-linked orchestras that played for student-related events in the 1930s and 1940s. Other bandleaders that orbited around the university scene included Dutch Scheel , Carnes Weaver , Red Camp , Clyde Mitchell , Joe Stanton , Jimmy Weiler , Gabe Martel , Jimmy Watson , Jimmy Ross , and a number of others.

Black Local Orchestras

All of the above bands were white. Black local orchestras did play for UT student dances on occasion, but the vast majority were given to white orchestras (especially to bands of current or former students). Information about black Austin orchestras is scarce, since their performances were often not covered by white Austin newspapers. When interviewed in the 1970s, the San Antonio swing bandleader Don Albert did not remember the Texas capital as a city with significant orchestras. There were “not too many name bands around Austin,” he remembered. The only white band he could recall was Herman Waldman’s . The only African American group that popped into his memory was that of the Corley brothers, George and Reginald.

Like many of the white Austin groups, the Corley brothers were students at a local college—Samuel Huston—and had a primarily local band. Scant evidence exists about them, unfortunately. After George, a trombonist, played with Troy Floyd ’s band in 1932, he led his own group in Austin, sometimes called the “Royal Aces” or “George Corley and his Swing Band.” Gene Ramey, who would later become a premier jazz bassist, played temple blocks in the band in the early 1930s. Ramey remembered that three Corley brothers were in it at the time: George, Reginald, and Wilfred.

From the few records of their performances available, we know they played at all sorts of venues between 1934 and 1939: at UT fraternity parties, for a baseball game in Riverside Park , at a tavern, at the Little Campus Gym , at the Avalon Dinner Club , and at one dance at Gregory in 1937. One ad for “Reginald Corley and his Royal Aces” appeared in 1933 for a battle dance at the Royal Auditorium. In addition to these gigs, there is one more article that shows that George Corley’s band played for a huge crowd during Juneteenth at the Doris Miller Auditorium in 1947. John Corley, possibly another brother, led an orchestra in Austin clubs in 1946-47.

Besides George Corley and his Royal Aces , Johnny Simmons’s Orchestra was probably the longest-lived black orchestras in town in the interwar and early post-World War Two era. Simmons kept a local group together from the late 1930s through the end of the 1940s and probably led the earliest jump blues/rhythm and blues band in Central Texas. One of his first bands, in 1938, was called the “Blue Devils,” possibly a tribute to Walter Page’s famous Kansas City band of the same name. He must have been a talented pianist, for he reportedly played with the Jimmie Lunceford orchestra, one of the most famous Swing outfits at the time. Lunceford often toured through Austin during this period and probably heard and hired him while in town.

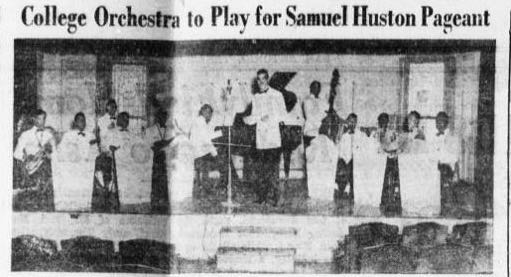

Brooks led the Sam Huston Rhythm Swingsters, which the largest black newspaper in Central and South Texas called “Austin and central Texas society’s most noteworthy exponent of Swing.”7 Drawn from students at Sam Huston, its members came from across Texas: Beaumont, Fort Worth, Seguin, and especially Dallas. Like other bands in town, the Sam Huston orchestra performed mainly for college audiences: lots of greek formals at UT, Sam Huston, and Tillotson college. They also performed for high schools and private clubs in San Antonio, Seguin, and other Texas cities.

The band often played a crucial role in community events in East Austin. It provided the music for a floral style show at Sam Huston college, which included appropriately themed music and dance to its “modernistic arrangements of flowers.”8 In 1939, Anderson High School held a historical pageant called “Three Centuries of Music and Dance.” The Sam Huston Swingsters performed during the section called “Music and dance in the age of Swing.”9 After Brooks left in 1940, George Corley took over the band;10 in the mid-1940s, Bert Adams , a composer and arranger, became its bandleader.

Karl Downs would become the president of Samuel Huston in the 1940s. Before he took over its leadership, however, he led the “Dragonians,” a “collegiate dance orchestra,” while studying there between 1932 and 1933. Downs’ band was well-regarded enough that it ranked in a best regional orchestras contest for the San Antonio Register.11

Regional Territory Orchestras

Austin was smack in the middle of two important Texas regional centers for jazz, swing, and dance orchestras: Dallas and San Antonio. Both had numerous upscale hotels, the most important and best-paying employers for orchestras in the territories during the period. They also had major clear channel radio stations, which provided the greatest opportunities for exposure and promotion through their broad range and expansive audiences. The Texas capital benefited by being in the overlapping periphery of these two cities. In addition to the national-level bands that appeared there on tour, Austin’s university audiences were also able to draw top Texas talent for dances from the North and the South.

Two very important regional black orchestras played in Austin during the 1930s: Alphonso Trent and Don Albert. When Alphonso Trent played at Gregory Gym in January 1932, he was approaching the end of his prime. Originally from Arkansas, Trent had led one of the most prominent dance bands in Texas in the second half of the 1920s. His group, made up of well-educated African American musicians with formal training, became nationally famous through their nightly WFAA radio broadcasts from the Adolphus Hotel between 1925 and 1926 (possibly the first broadcasts in the Southwest by a black orchestra). Before the onset of the Depression, the group had been quite successful, especially for an African American band. They played long engagements at elite white-only hotels in Dallas (the Adolphus), San Antonio (the Gunter and Plaza), Galveston (the Galvez), and Houston (the Rice). Hotel gigs were probably the most desirable form of employment available, since they were stable and well-paying. Part of the broader inequity of opportunity during the Jim Crow era, they were typically awarded to white bands, however.

Although not well known now, Trent’s band was deeply respected and influential in the 1920s and early 1930s. Buddy Tate, a Texan saxophonist who joined the seminal Count Basie orchestra of the late 1930s, remembered that Trent’s group “were outplaying Duke…If they would have kept going they would have been as big as Duke or any of them.”12 On a visit to Dallas, Paul Whiteman, the most famous bandleader in America during the period, brought his entire group to one of Trent’s performances at the Adolphus.13

The career of Don Albert was linked to Alphonso Trent. Like Trent, he was not originally from Texas, although he became the leader of one of its most well-known African American orchestras. Albert originally immigrated to Texas in 1926 in order to play with the Trent band. After playing a short stint with the group, he moved on to play with Troy Floyd’s band at San Antonio’s Shadowland.

Albert led his own bands between the 1929 and the 1950s (he later opened up one of the first integrated clubs in Texas, the Keystone Club). His group was the epitome of the regional territory band—using San Antonio as a home base, they toured extensively. Originally from New Orleans, Albert represented the crucial wave of migrants from the Crescent City and Louisiana into Texas during the first few decades of the twentieth century. Like the clarinetist Herb Hall, who played with Albert, the trumpet player brought with him the unique vernacular brass band traditions of New Orleans and represented the merging of early jazz culture with the regional dance culture of Texas.

Unlike many of the regional territory bands of the period, Albert’s band was on the cusp of national fame during the 1930s. Clark Terry, who played trumpet and flugelhorn with Duke Ellington in the 1950s and 1960s, remembered that Albert “was one of the most respected bandleaders and businessmen. Aside from Duke Ellington and Jimmie Lunceford, there wasn’t a more highly thought of black dude around. Good trumpet player, too. That band he had in the late thirties was a perfectionist’s band.”15

When Albert began to play in Austin, he led a well-known regional band in Texas, Louisiana, and possibly other parts of the Southwest. Right after his first performances in Gregory Gym and the Royal Auditorium, he attempted to enter the ranks of national “name” bands. Renaming his group “Don Albert’s Music: America’s Greatest Swing Band,” he began a series of tours across the United States. Between 1933 and 1940, the band travelled all over the South, Midwest, and Northeast, taking him from Texas to Florida to New York and Illinois. By the time, he played at UT and the Cotton Club again in the late 1930s, his band had a significantly different stature.

Notes

- Gunther Schuller, The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz, 1930-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 772. ⏎

- “Town Talk” Austin Statesman, October 31, 1933, 4. Bureau of Labor Statistics. ⏎

- Daily Texan June 17, 1937, 1. ⏎

- “Town Talk,” Austin Statesman (July 22, 1929). ⏎

- Dave Oliphant, Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2007), 17-18. ⏎

- Daily Texan (March 23, 1939). ⏎

- San Antonio Register (May 12, 1938) ⏎

- San Antonio Register December 3, 1937, 8. ⏎

- San Antonio Register May 12, 1939, 2. ⏎

- San Antonio Register April 19, 1940, 7. ⏎

- San Antonio Register December 9, 1932, 2; San Antonio Register January 13, 1933, 6. ⏎

- Frank Driggs, “Buddy Tate, My Story,” Jazz Review (December 1958), 6. ⏎

- Henry Q. Rinne, “A Short History of the Alphonso Trent Orchestra,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 45, No. 3 (1986), 236. ⏎

- “Trent’s Orchestra Will Appear Here,” Daily Texan, January 7, 1932. ⏎

- As quoted in Douglas K. Ramsey, Jazz Matters, Reflections on Music and Some of Its Makers (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1989), 32. ⏎

- Daily Texan (April 8, 1931). ⏎