Western Swing in Austin, Part I: 1940-1950

Austin’s live music scene in 1946 sounded quite different than it had before the start of the Second World War. During the previous few years, new music spots had popped up on its primitive highways all around the city. These new venues, most of them Honky Tonks, featured bands playing a relatively recent regional style: Western Swing. This was a big change for the area's night clubs. The Windmill and the Barn hired small electrified Country and Western bands, not the big dance and swing orchestras that had been so in demand in the city during the 1930s. Attracting different audiences than the older clubs, their dancers favored music and bands that weren't previously hired by places like the Avalon or the Tower.

Western Swing—one of the most lasting and unique cultural products of Depression-era Texas—did not find an early home in Austin. At first glance, this may be surprising. The capital city has not only been considered the musical nerve center of the state for decades, but it has also been closely identified with Western Swing since the style’s high profile local revival by Asleep at the Wheel and Alvin Crow during the 1970s. Despite this later connection, modernist hillbilly bands and rural rhythm groups did not gain much traction in Austin during their earliest period of innovation.

This began to change during World War Two and its aftermath. Over the course of the 1940s, Western Swing (and Honky Tonk Country) rose to an unprecedented prominence in Austin. As local music historian Michael Corcoran has pointed out, Austin was “dominated by Western Swing bands like Jesse James and All the Boys , Jimmy Heap and the Melody Masters , Doug and the Falstaff Swing Boys, Buck Roberts and the Rhythmairs, and Dolores and the Blue Bonnet Boys” between 1945 and the rise of Rock and Roll in the mid-1950s.1

This shift had begun at the beginning of the 1940s. Western bands began to get a new foothold on the northern and southern outskirts of the city, as dance halls sprang up on the Dallas and San Antonio highways over the course of the decade.2 The new sound represented a new population of patrons in Austin: working class whites and G.I.s from the area’s new military installations.

Austin as Outlier

As these early Western Swing scenes quickly got off the ground, Austin was and largely remained a big band and “sweet” music town. This does not mean that Western bands and “Hillbilly” music was totally absent. Dessau Hall was the music’s first center in the area and probably the city’s earliest Western Swing group, Uncle Walt and his Rural Rhythm , played on local radio in the late 1930s. Despite this early presence, Uncle Walt and other similar groups remained marginal compared to the dance, jazz, and swing orchestras that catered to the university crowd(s).

Western Swing Finds a Home, 1940-1945

Beginning in 1941, modern Hillbilly and Rural Rhythm bands began to gain a foothold in the Texas capital. It was “The Barn” and “The Sunset Tavern ” that seem to have set in motion the slow but steady growth of the Western Swing presence around Austin. “The Barn,” opened in 1940, was 16 miles north on the Georgetown/Dallas Highway (now North Lamar). It was a re-christening of the “Cocklebur Barn ,” a venue that had hosted probable Western Swing groups like Lee Fariss and his Dixieland Band (with Uncle Walt on steel guitar) in 1938 and 1939.4 The Barn, and its predecessor, built on the regular dances at Dessau Hall by Uncle Walt's Rural Rhythm and the Radio Ranglers during the second half of the 1930s. Dessau was the true progenitor of the local Western Swing scene, but the addition of the Barn ultimately brought in both new acts and multiplied the weekly performances.

In mid-1941, however, the dance hall switched to almost exclusively Western groups, bringing in the Lonesome Cowboy and his Cowhands , Allen Thomas and his Blue Jackets , Boots and his Texas Melody Boys , and Adolph Hofner (from San Antonio) over the next few years. They also hired new editions of the pioneering bandleaders of the 1930s, providing a new home for Steve Lightsey and his Rhythm Kings and Uncle Walt and his Melody Boys. Although this change in booking preceded the U.S.’s entrance into the war in December 1941, the Barn was well positioned to take advantage of the huge new G.I. populations that began to arrive the following year.

The Sunset Tavern opened the same year as the Barn, but records of performances for it are fairly sparse during its early years. “Kittie and Her Kittens,” who played regularly at Dessau Hall and were probably a female-led Hillbilly group, also did Tuesday night gigs there in June 1940. There wasn’t another ad, however, until 1942, when “Grouchy and the Texas Pioneers ” played with Bob Dunn, the most important early innovator on the steel guitar.5

The Big Expansion, 1945-1950

The Western Swing scene in Austin blossomed vibrantly after the end of World War Two. Between 1946 and 1947, Honky Tonks began to line the highways in all directions, especially those going North and South from the city. On the Dallas Highway, East Ave., and around Round Rock, there was the Barn, the Skyline Club, Dessau Hall, the Owl Club , and the Star Club . Northwest of town and on the Burnet Highway (now Burnet Rd.), there was the Copenhagen Inn , the Hilltop Inn , and the Sunset Tavern. The San Antonio Highway (now South Congress Avenue) down South had its own long row of venues that hired Western Swing bands: the Cinderella Club , the Village , the Windmill, the Trocadero Dinner Club /El Morocco , and Club 81 . West and Southwest, the Elm Grove Lodge was on Bee Cave Road while the Moose Head Tavern and the Blue Goose opened up on the Fredericksburg Road. Tellingly, East of Austin was the exception, with no white Honky Tonks appearing on the outskirts of the black and Mexican American side of the city.

Thompson, Heap, Choates, and Capitol Records

Austin remained largely a working musician town during these years. Since there were only a couple of small labels sporadically active in the city, just a few local bands made a handful of recordings. There were three musicians who lived and worked in Austin’s orbit during these years that consistently entered the studio and had a presence beyond the region, however: Hank Thompson, Jimmy Heap, and Harry Choates . Thompson, who would become a massive star in the Country world in the 1950s, was only in the area for his first few years of recording before he made Oklahoma City his home base in 1952 (with spells in Nashville and Dallas in between). Originally from Waco, he had a number of regional and national hits with “Humpty Dumpty Heart,” “Green Light,” and “What are we going to do with all the Moonlight” in 1948. Lefty Nason, whose unique steel playing supplied Thompson a large part of his signature sound, was in Austin with Jesse James before Hank snatched him up for his band.6

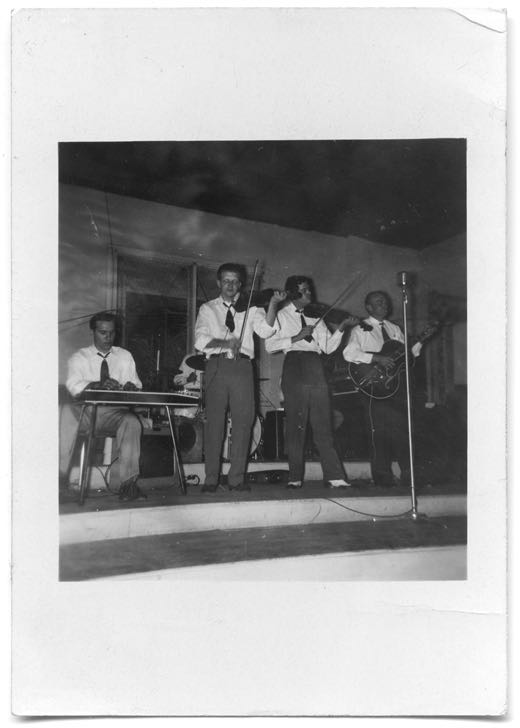

Hank Thompson and Jesse James at Dessau Hall, date unknown.

[Photograph of Hank Thompson and Jesse James], photograph, Date Unknown; accessed December 18, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Museum of the Gulf Coast.

Thompson’s breakthrough came in 1952 with “Wild Side of Life,” a tune composed and first recorded by another Austin area band, Jimmy Heap and the Melody Masters. Heap’s original 1952 version on Imperial brought them attention and sales in Texas, but it was minor compared to the splash made with by Thompson and the Brazos Valley Boys. The Melody Masters were perhaps the quintessential representatives around Austin of Honky Tonk Country, a native style related to Western Swing but rawer and more focused on emotional lyrics about heartache, sexuality, betrayal, and violence. Honky Tonk Country evolved, as its name implies, in the Skull orchards and roadhouses around Dallas, Houston, and the Texas Hill Country in the late 1930s, as musicians like Ernest Tubb, Floyd Tillman, and Al Dexter adapted Hillbilly music to these new environments. The style placed less emphasis on the dance-driving four-four beat of Western Swing and centered itself more on the singer. As a band that made their living playing the Central Texas dance halls and road houses, the Melody Masters were versatile. Heap “possessed a big repertory of Bob Wills-style songs, but they also featured beer-drinking tunes, then becoming paramount in Country Music.”7

Thompson and Heap were both on Capitol Records, based in Los Angeles. Paralleling much of the westward migration that had occurred in 1930s and early 1940s, there seemed to have been a Central Texas-Capitol connection. The label had, in fact, started its Country roster with Tex Ritter, a UT graduate who was inspired to go into Cowboy music by his study of folklore in Austin with J. Frank Dobie. Ritter had recommended Hank Thompson to the label after hearing him in Waco on tour in 1946. If Capitol was “the great postwar catalyst for southwestern and particularly West Coast country,” as author Rich Kienzle has argued, the Austin area scene, through Thompson and Heap, played a key role in it.0

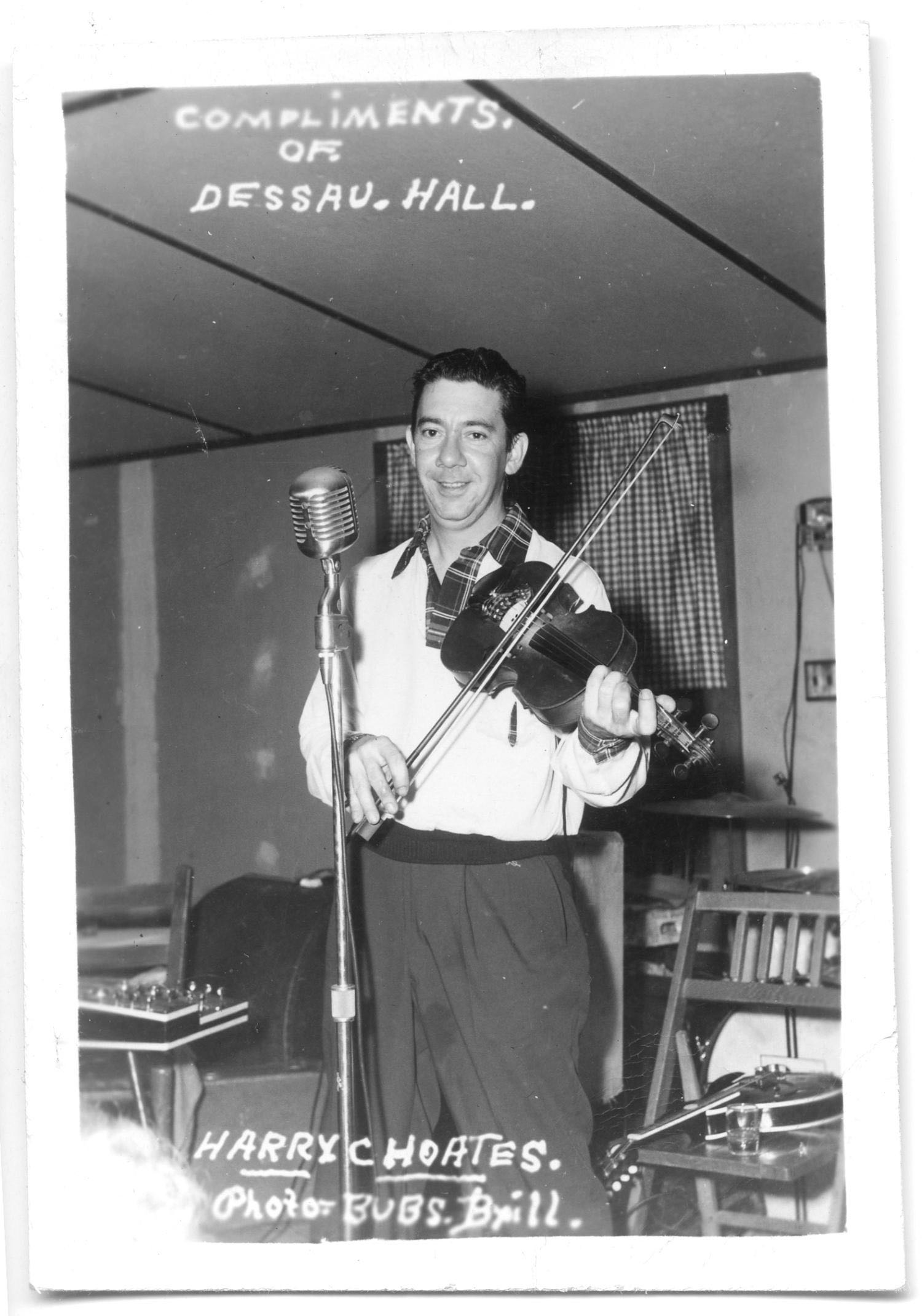

Austin also became the home and tragic end point of Harry Choates, perhaps the most original musician in its postwar Honky Tonk scene. Choates, born in South-Central Louisiana, blended the developing sounds of cajun music with Texas Western Swing in Port Arthur, where his family moved during the Depression. A representative of the musical borderlands of East Texas-Western Louisiana, he recorded “Jole Blon” at the famed Gold Star studios in Houston in 1946, the recording that would ultimately make it one of the most iconic tunes in cajun music’s repertoire.

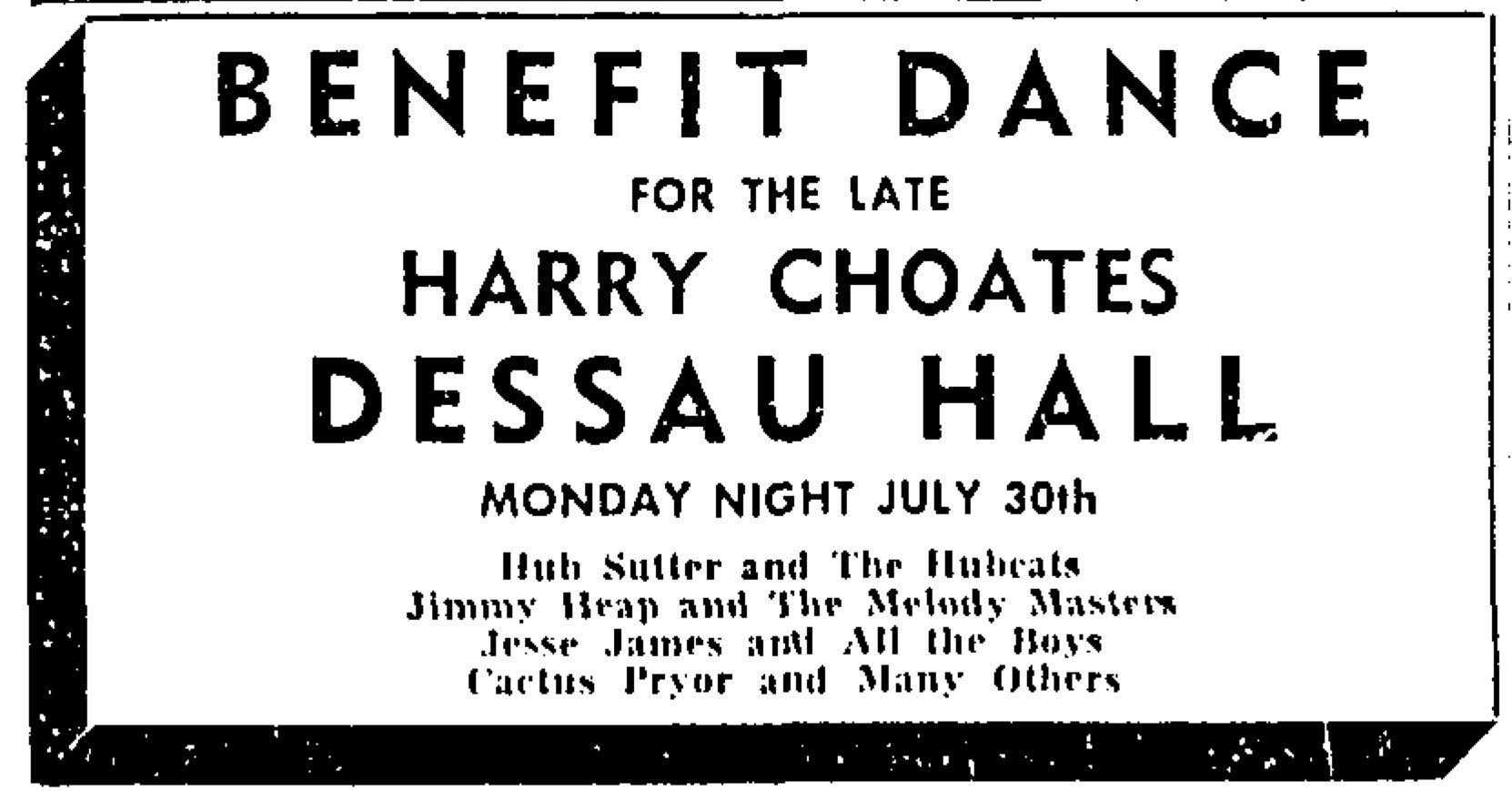

Harry Choates at Dessau Hall, 1947-1951.

Brill, Bubs. [Photograph of Harry Choates], photograph, Date Unknown; accessed December 18, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Museum of the Gulf Coast.

Choates began playing Austin in 1947 and his “Original Jole Blon Band” was a staple at the Barn, The Windmill, and Dessau Hall for the next year. After a two year absence, he re-located to Austin in 1950, where he became the star fiddler in Jesse James’s band. Choates was a magnificent and inspiring performer, but unruly and unreliable. By the time he returned to Austin, he had been overwhelmed by substance abuse for years and, within a short time, had split with his wife. On July 7, 1951, he died in a Travis County jail cell after being arrested for outstanding child support payments. Rumors of a police beating have circulated for decades, but, according to his bandmate Jimmy Grabowske, he was in deep and dangerous alcohol withdrawal the day he died, making it quite possible that he died from complications from the DTs (Delirium Tremens). Choates’s last session in June 1951 contained the song “Austin Special,” the singer’s own depiction or tribute to his recently adopted city.8

Harry Choates, “Austin Special” (Allied, 1951). The title on this YouTube video is mislabeled “Saturday Night Waltz.”

The Austin-Nashville-Shreveport Nexus

If Capitol Records in LA created a Western music connection between California and Central Texas, Dessau Hall and the Skyline Club created direct lines from Austin to Shreveport and Nashville, the homes of the immensely popular Louisiana Hayride and Grand Ole Opry radio shows. This didn’t happen with any regularity before the early 1950s, however. During the 1940s, the Central Texas Honky Tonk scene was a very regional affair. Dances around Austin were played almost exclusively by area bands like Jesse James or Boots and his Texas Melody Boys, with occasional performances from groups from Dallas and San Antonio.

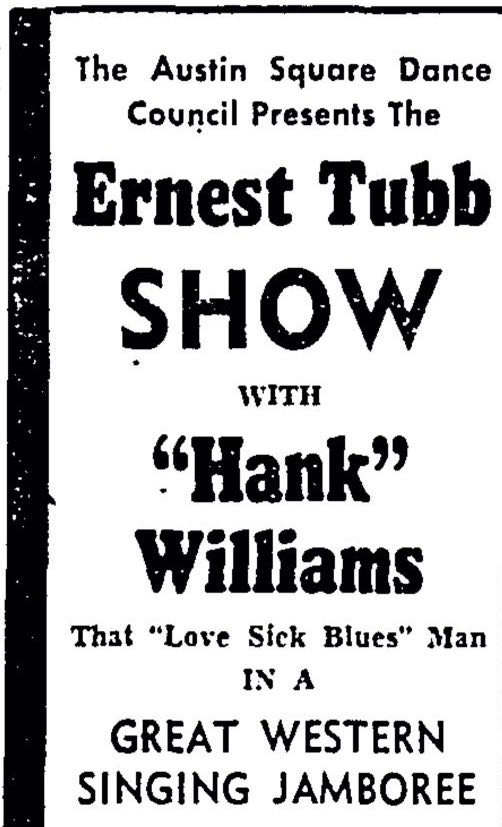

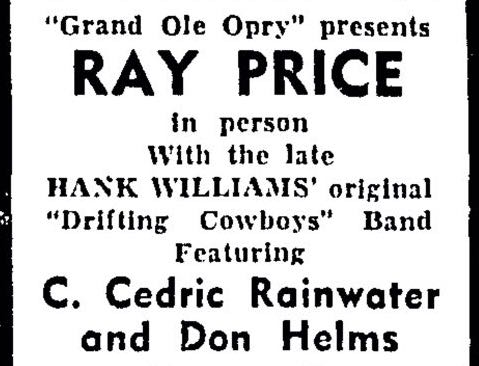

Realizing that Austin had a large and devoted enough fan base to support touring acts, local Honky Tonks began to establish connections with the expanding and centralizing Country and Western music industry of the early 1950s. In 1951 and 1952, the Skyline Club and Dessau Hall began to book musicians from the Louisiana Hayride and the Grand Ole Opry, including Webb Pierce, Okie Jones, Red Sovine, Carl Smith, Kitty Wells, the Tennessee Mountain Boys, and Ray Price. That they were considered something special was clear in the shows' advertising: they shelled out the money to print the artists' photographs and prominently identified them as radio stars.

The appearances of major Nashville and Shreveport performers in Austin increased remarkably in 1953. That year, the Skyline’s owner, Warren Stark, established the “Skyline Jamboree,” a weekly Thursday event. Determining that “the string-music field in Austin could stand a little special notice,” Stark decided to “[devote] every Thursday night at his club to bringing in outstanding stars of Western music.” To do so, he simply intensified what he and Dessau had already been doing: drawing in major acts from the two major Country radio programs in Nashville and Shreveport.9

It was in this context that the Skyline Club hosted the famous last performances of two stars, Hank Williams Sr. and Johnny Horton. Symbolically and not coincidentally, both tragic deaths involved cars and travel. The dance hall saw the last public show by Hank Williams before he had a heart attack on the way to a concert in Canton, Ohio on January 1, 1953. Seven years later, Johnny Horton played the Skyline just before he perished in a harrowing car wreck, as he quickly drove from Austin to Shreveport to make a Louisiana Hayride broadcast.

The popularity of Western Swing and Nashville stars at Austin Honky Tonks also spurred the scene to briefly try to branch out into other kinds of music. During roughly the same period that the Skyline started its jamboree, Dessau Hall expanded its programming in a different direction. Trying to expand its audience beyond its “Hillbilly” fans, the old German community center began to book orchestras and Swing bands. In November 1952, its proprietor, D.R. Price, “decided to experiment by using popular music organizations in addition to the regular western groups that frequent the hall.” After their first show with the Tex Beneke big band sold out, Dessau committed to a “new name-band policy” that brought “top quality dance bands once a month [to] the Western music stronghold.” For a few years, Swing and easy listening orchestras, including the famous groups of Artie Shaw and Stan Kenton, co-existed on Dessau's yearly program with Faron Young, Carolyn Bradshaw, Goldie Hill, and Webb Pierce. By the mid-1950s, this experiment with multiple styles and audiences came to a halt and Dessau reverted to being an almost exclusvely Country venue.10

Notes

- Michael Corcoran, “Ramblin’ Ray Remembers: Austin Music in the 1950s,” (April 1, 2012); Michael Corcoran, “Secret History of Austin Music, part 3: Dolores and the Blue Bonnet Boys,” Austin American Statesman (October 21, 2016). ⏎

- The Dallas Highway is now North Lamar Blvd. and the San Antonio Highway is South Congress Ave. ⏎

- Malone, Country Music USA ⏎

- Although it’s not totally clear what this band played, some early Western Swing bands used the term “dixieland” for their groups, even though the term would later strongly denote a revivalist New Orleans-style jazz ensemble. Lee Fariss was the husband of Dolores Fariss, the singer for the 1940s Western Swing group “Dolores and her Bluebonnet Boys.” ⏎

- Austin Statesman (August 3, 1940); Austin Statesman (August 3, 1940); Austin Statesman (May 16, 1942). ⏎

- Rich Kienzle, Southwestern Shuffle: Pioneers of Honky-Tonk, Western Swing, and Country Jazz (New York: Routledge, 2003), 135. ⏎

- Bill C. Malone, Country Music U.S.A. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 266. ⏎

- Michael Corcoran, All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005), 6-9. ⏎

- “Western Music Jamboree Slated at Skyline Club” Austin American (August 30, 1953). ⏎

- Austin American (November 9, 1952); Austin American (December 14, 1952); Austin Statesman (February 11, 1953); Austin Statesman (March 16, 1953). ⏎