National Bands

During the 1930s and 1940s, a remarkable number of “name“ national bands played for UT, Samuel Huston, and Tillotson students. This was notable, since Austin was a small city on the edge of the arid and rural Texas Hill country, far from the metropolitan music industry centers in the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. Achieving success as a pop orchestra typically meant being away from such out-of-the-way locations. Despite being in a fairly remote place, young music fans at UT got to see, listen, and dance to some of the most well-known and acclaimed dance orchestras in the country at the time. The presence of the university was undoubtably a major reason why the top orchestras in the country came to Austin. But their concerts also show the increasing reach of the national music industry at the time: these bandleaders were not just stars where they lived and played, but to young Americans flung across the wide expanse of the continent.

At the time, all of these bands were at the pinnacle of pop music. Some of these performers are now remembered as essential to the history of jazz and American music: for example, Louis Armstrong , Duke Ellington , Benny Goodman , Jimmie Lunceford , Earl Hines , and the Dorsey Brothers. They played in Austin when they were transforming popular music. Other groups were equally significant at the time, but history and critics have been less kind to them. Many have receded into obscurity and/or been dismissed as inauthentic or musically bland, like Guy Lombardo , Vincent Lopez , and Kay Kyser .

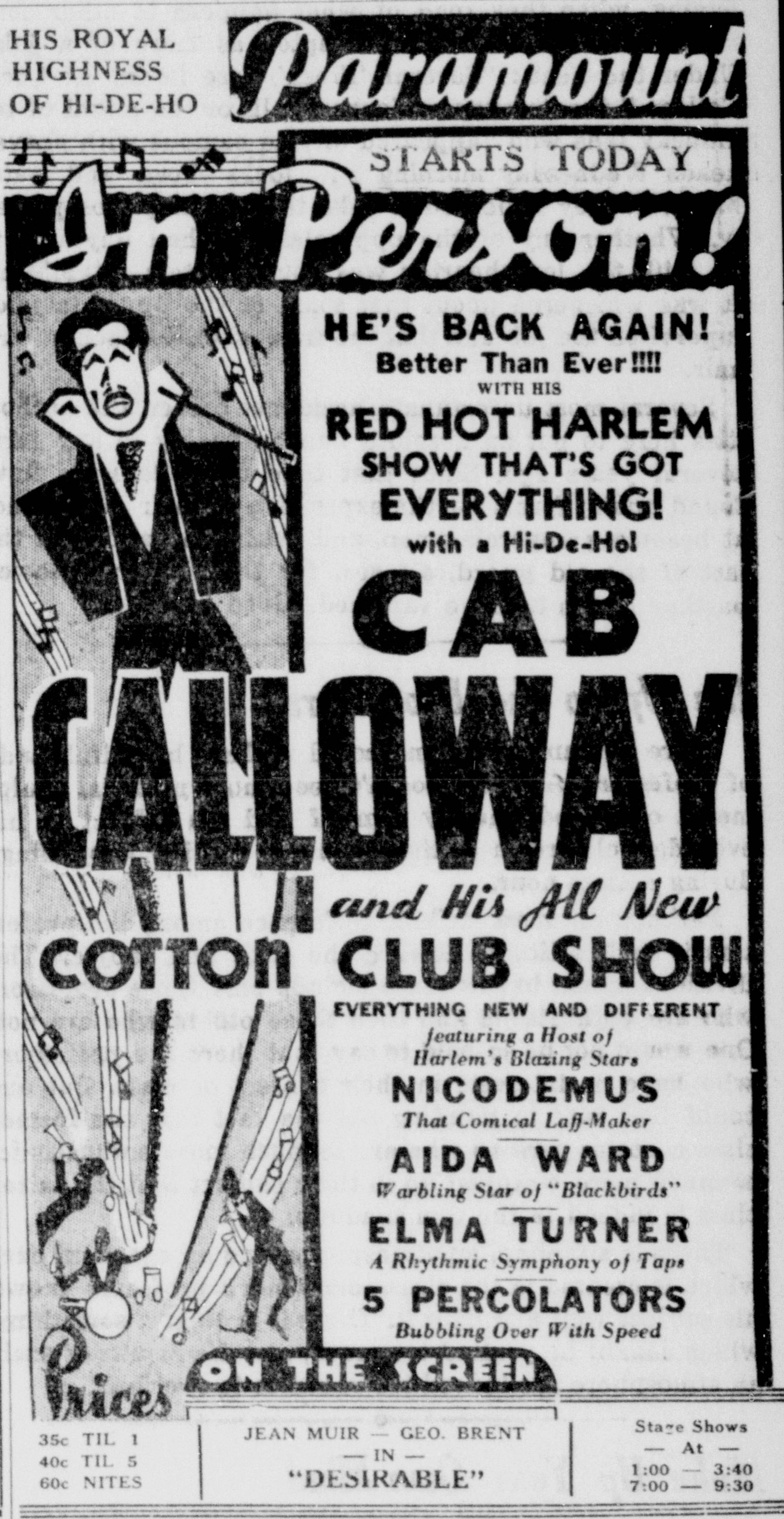

Most of these concerts happened as “All University Dances” in the Union or Gregory Gym on UT campus, since typically only a large institution like the university could marshall the money, people, and space to bring major bands to town. But this was not always the case. After the mid-1930s, fraternities, sororities, and clubs also managed to get ”name“ groups to play at venues around campus, like the Texas Federated Women’s Club and the Austin Country Club (now Hancock Golf Course). The Royal Auditorium and Cotton Club on 11th street also brought major bands to East Austin, although we only have records of (probably) a fraction of the performances.

A Selected List of National Bands that Played for UT-Related Events, 1930-1946

1931

- Louis ArmstrongGregory GymSeptember 26

1932

- King OliverAustin Country ClubNovember 26

1933

- Frankie MastersGregory GymApril 8

- Henry BusseTexas Union/Gregory GymSeptember 18-20

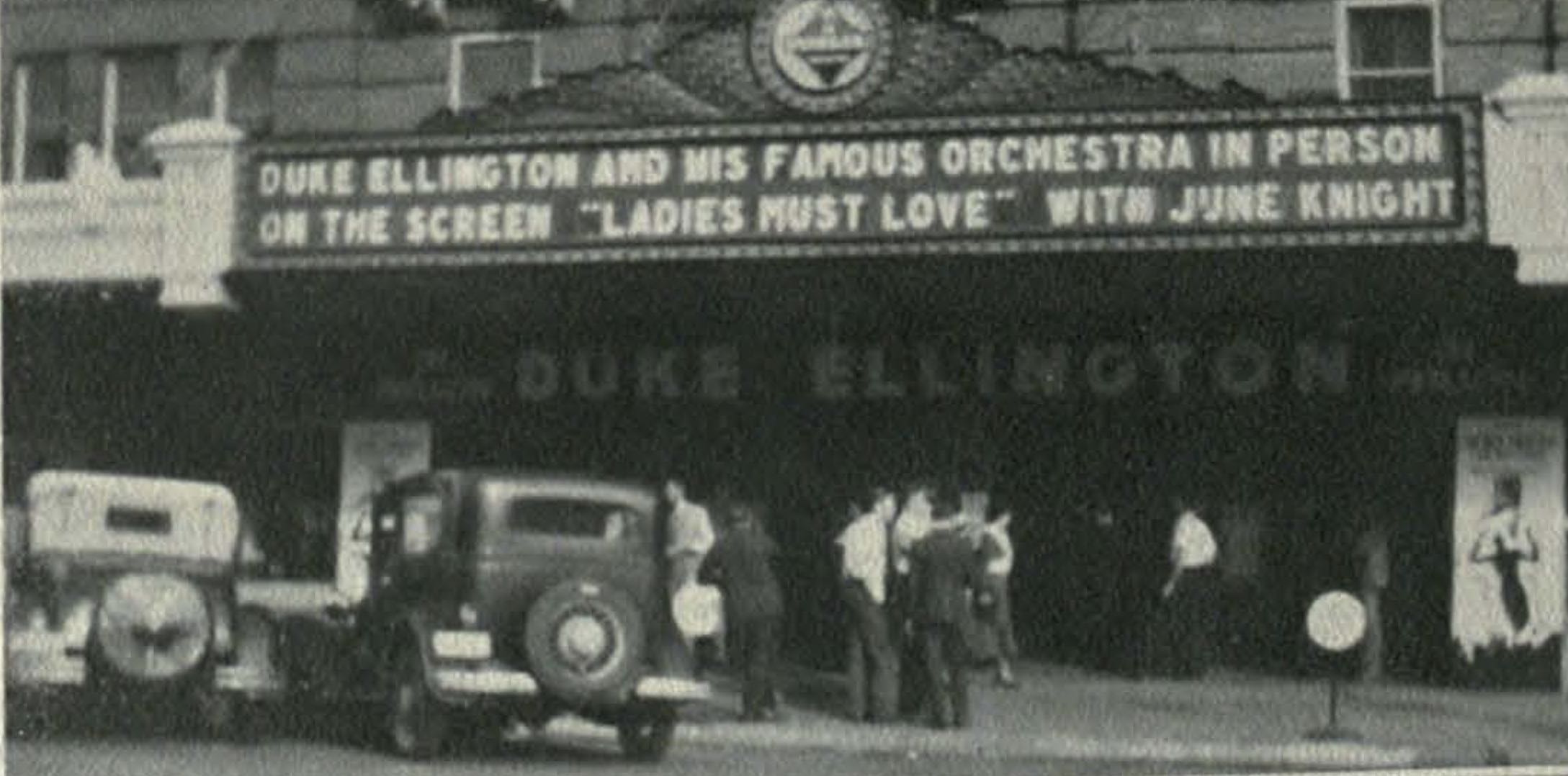

- Duke EllingtonGregory GymOctober 12

1934

- Vincent LopezGregory GymNovember 11

1935

- Guy LombardoTexas Union/Gregory GymFebruary 2

- Benny GoodmanTexas UnionNovember 2

1936

- Joe VenutiTexas Federated Women’s ClubFebruary 15

- Jimmie LuncefordGregory GymMarch 9

- Paul WhitemanHogg Memorial AuditoriumSeptember 9

- Duke EllingtonTexas UnionNovember 26

- Joe ReichmanAustin Country ClubDecember 11

- Ted Fio RitoGregory GymDecember 19

1937

- Herbie KayTexas Union/Gregory GymFebruary 19

- Carol LofnerTexas UnionMarch 6

- Joe VenutiGregory GymApril 16

- George OlsonGregory GymMay 15

- Jackie CooganGregory GymSeptember 30

- Jimmie LuncefordGregory GymOctober 7

- Shep FieldsGregory GymNovember 13

- Red NicholsGregory GymDecember 18

1938

- Jimmie LuncefordGregory GymFebruary 26

- Herbie KayTexas Federated Women’s ClubMarch 11

- Glen GrayGregory GymMarch 16

- Anson WeeksTexas UnionApril 2

- George HamiltonGregory GymApril 8

- Joe ReichmanTexas UnionApril 30

- Eddie FitzpatrickGregory GymSeptember 16-17

- Joe ReichmanGregory GymSeptember 24

- Gabe MartelTexas Federated Women’s ClubNovember 24

- Henry BusseTexas Federated Women’s ClubNovember 25

- George HamiltonTexas UnionDecember 10

1939

- Gabe MartelAustin Country ClubJanuary 6

- Eddie FitzpatrickTexas Federated Women’s ClubMarch 10

- George HamiltonAustin Country ClubApril 14

- Joe VenutiTexas Federated Women’s ClubMay 13

- Jan GarberTexas Union/Gregory GymSeptember 30

- Leonard KellerTexas UnionOctober 7

- Happy FeltonGregory GymOctober 21

- Vincent LopezTexas Union/Gregory GymOctober 28

- Erskine HawkinsTexas Women’s Federated ClubNovember 3

1940

- Vincent LopezTexas UnionMarch 1

- Del CourtneyGregory GymApril 5

- Jimmie LuncefordStephen F. Austin HotelApril 19

- Ozzie NelsonGregory GymSeptember 21

- Malcolm BeelbyGregory GymSeptember 28

- Hal KempGregory GymOctober 18

- Al DonahueGregory GymNovember 28

1941

- Jan GarberGregory GymFebruary 14

- Bernie CumminsTexas UnionFebruary 28

- Jimmie LuncefordTexas UnionMarch 7

- Count BasieGregory GymMarch 21

- Duke EllingtonTexas Federation of Women’s ClubApril 19

- Kay KyserGregory GymApril 25

- Eddie FitzpatrickTexas Union, May 9

- Dick SmithGregory GymOctober 3

- Red NicholsTexas Federation of Women’s ClubsNovember 22

1942

- Jimmie LuncefordGregory GymFebruary 20

- Wayne KingGregory Gym, March 6

- Tommy Dorsey with Frank SinatraGregory GymMarch 13

- Erskine HawkinsGregory GymSeptember 18

- Louis ArmstrongGregory GymDecember 11

1943

- Jack TeagardenGregory GymSeptember 17

- Fletcher HendersonGregory GymOctober 2

- Benny CarterGregory GymNovember 20

1944

- Tommy DorseyGregory GymJuly 9

1945

- Carol LofnerTexas Federation of Women’s ClubsJanuary 13

- Billy EckstineTexas UnionJanuary 27

- Stan KentonGregory GymApril 6

- Jimmie LuncefordGregory Gym, May 12

- Benny CarterGregory GymNovember 10

1946

- Henry BusseGregory GymJanuary 5

- Johnny “Scat” DavisGregory Gym, March 16

- Jimmie LuncefordTexas Federation of Women’s ClubMarch 22

- Duke EllingtonGregory GymApril 13

- Jan GarberGregory GymApril 27

- Van KirkpatrickGregory GymSeptember 21

- Glenn Miller with Tex BenekeGregory GymNovember 22

- Frankie MastersGregory GymNovember 27

- Xavier CugatGregory GymDecember 5

- Dizzy Gillespie with Ella FitzgeraldGregory GymDecember 14

How Star Orchestra Concerts Happened: Radio and Booking Agencies

We should remember that it wasn’t a given that UT students would care about big bands from out-of-state and be willing to pay more to see them perform. The consistent presence of star orchestras was a phenomenon of the 1930s; just a handful of dances by non-native groups happened during the whole of the decade before. Three things created the conditions for why national band All University Dances happened: radio, booking agencies, and touring.

Orchestras like Benny Goodman’s or Jimmie Lunceford’s became “name” bands through the radio. The Depression caused a virtual collapse of the record industry and, during the 1930s, most Americans got their pop music through radio and film. The dominance of radio in the 1930s and the appearance of national bands in Austin were interconnected. Radio’s ability to focus so much attention on a handful of ensembles made possible the existence of “name” bands and celebrity bandleaders. Without radio, UT students would likely have never heard of nor gone to see Ellington, Lunceford, Dorsey, and Lombardo.

The “name” band concerts at UT were also dependent on the presence of large corporate booking agencies, which became increasingly prominent in the first half of the 1930s. The booking agencies exerted incredible power over bands—often taking large chunks of their incomes—by controlling access to radio broadcasts, the best concert venues, and recording/film contracts. They also managed promotion, advertising, and booked tours. The tours that brought Tommy Dorsey and Xavier Cugat to Austin happened because of the existence of these expansive corporations. In fact, most of the bands that played at UT came from the largest and most powerful agency, the Music Corporation of America, which had a student representative (Jimmy Phillips) to the Dance Committee in the Texas Union.

The Dust, Sweat, and Danger of Touring

Getting to Austin was often a grueling task. Most of this period was before the national highway system and many roads were rough and slow-going. During the war, rationing of gasoline and rubber made touring even more difficult, if not impossible (much to the chagrin of UT students, both the 1943 and 1944 Spring semesters had no “name” bands). Large national bands often did dozens of consecutive one-nighters: playing a dance, packing up, travelling to another town, and performing the next night somewhere else. On these tours, groups would criss-cross the nation in the months surrounding their performance at UT.

Count Basie’s Tour, January 1941 - April 1941

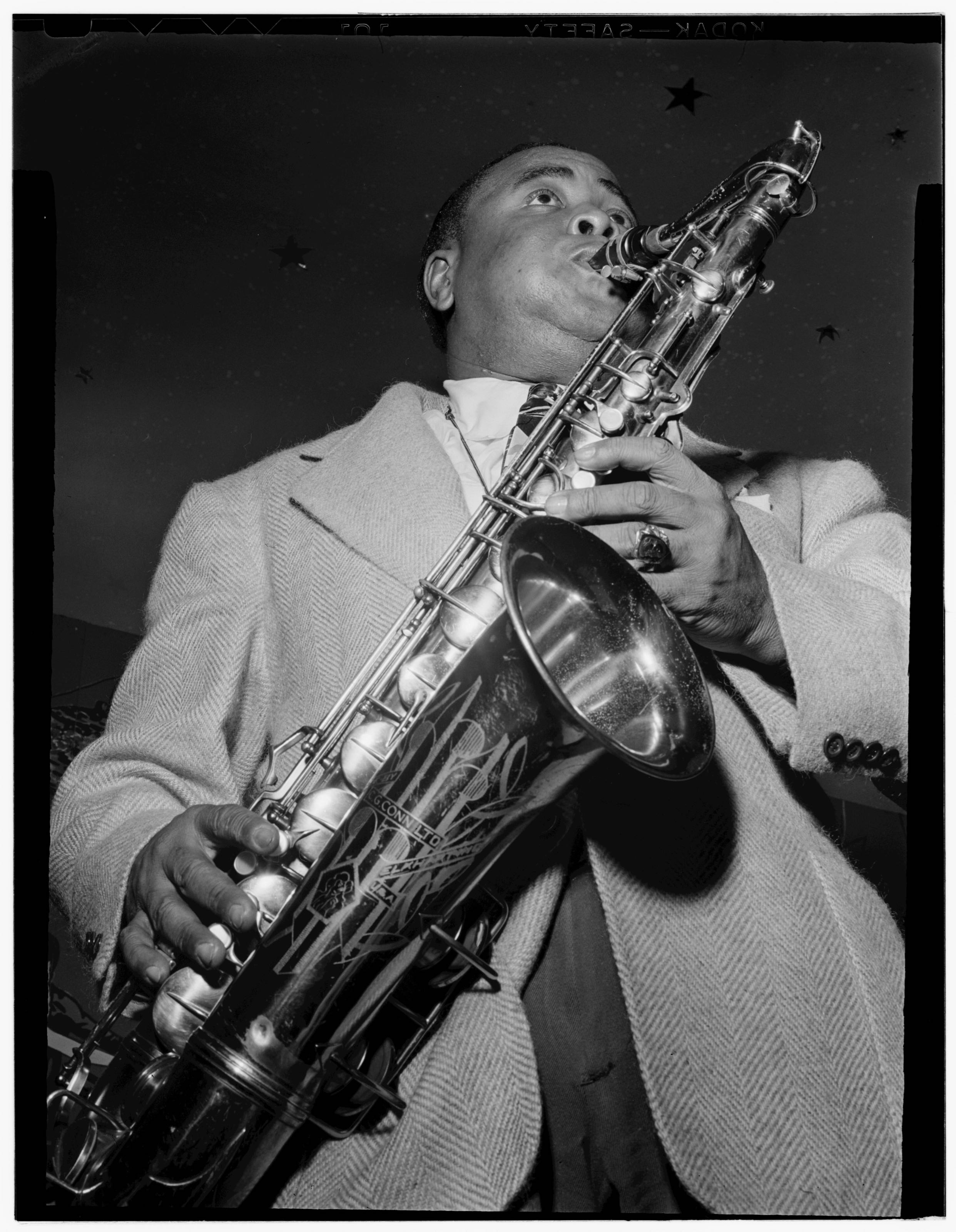

Gene Sedric, tenor saxophonist and clarinetist, played with Fletcher Henderson and Fats Waller during the 1930s.

Gene Sedric, 1946

William P. Gottlieb. Portrait of Gene Sedric, The Place, New York, N.Y., ca. July. United States, 1946. Monographic. Photograph.

If the band or musician was African American, the already difficult life on the road could also be dangerous and full of humiliating reminders of America’s inequality. Black musicians who travelled from large urban centers in the North to one-night stands in the Jim Crow South crossed into worlds that had new and unfamiliar social rules of white supremacy. Consequentially, they could face brutal racist violence for doing what seemed like basic, everyday things, like speaking to a white friend or eating at a white-owned restaurant.

The saxophonist Charlie Rouse, who grew up on the edge of the South in Washington D.C., recalled a violent experience he had on a Southern tour with Dizzy Gillespie in 1945 (a year before the band visited UT).

Charlie Rouse, saxophone (left), 1946 - 1948

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Charlie Rouse, Tadd Dameron, Fats Navarro, and Ernie Henry, New York, N.Y., Between 1946 and 1948. United States, 1946. Monographic. Photograph.

Evidence about how national bands experienced these gigs in Austin, how they perceived Texas, or what happened before and after while travelling through the South is scarce. Although relatively rare, some of these musicians did mention these tours in interviews and autobiographies. Below are some scattered memories and impressions surrounding these concerts at UT in the 1930s and 1940s:

Duke Ellington

Gregory Gym

October 12, 1933

Duke Ellington, 1938 - 1948

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Duke Ellington, Washington, D.C., Between 1938 and 1948. United States, 1938. , Monographic. Photograph.

Juan Tizol

Trombonist in the Duke Ellington Orchestra

Gregory Gym

October 12, 1933

Juan Tizol, 1946-1948

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Willie Smith and Juan Tizol, New York, N.Y., Between 1946 and 1948. United States, 1946. , Monographic. Photograph.

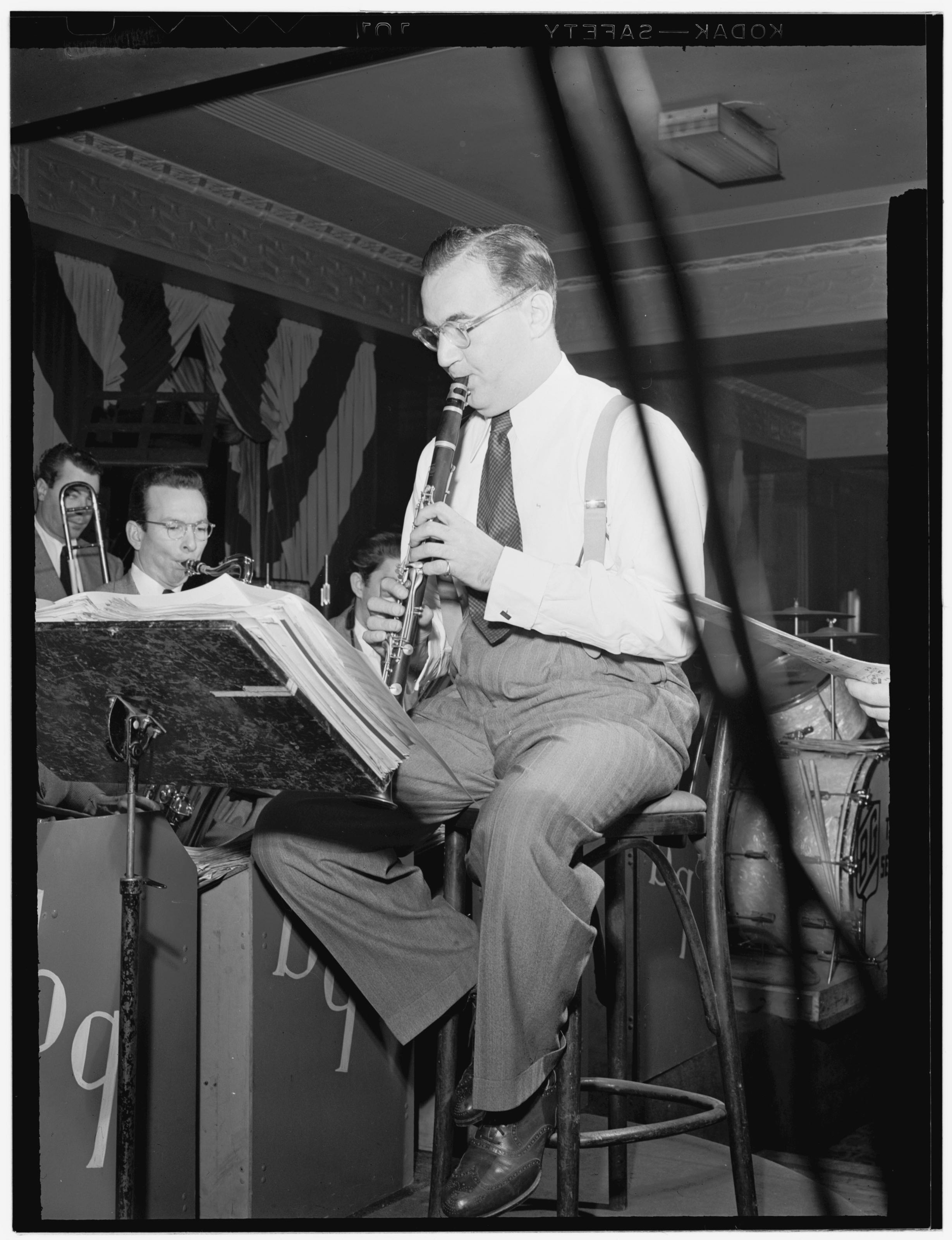

Benny Goodman

Gregory Gym

November 2, 1935

Benny Goodman, ca. July 1946

William P. Gottlieb. Portrait of Benny Goodman, 400 Restaurant, New York, N.Y., ca. July. United States, 1946. Monographic. Photograph.

Duke Ellington

Texas Union

November 26, 1936

Duke Ellington Orchestra, between 1938 and 1948

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Duke Ellington, Junior Raglin, Tricky Sam Nanton?, Juan Tizol, Barney Bigard, Ben Webster, Otto Toby Hardwicke, Harry Carney, Rex William Stewart, and Sonny Greer, Howard Theater?, Washington, D.C., Between 1938 and 1948. United States, 1938. Monographic. Photograph.

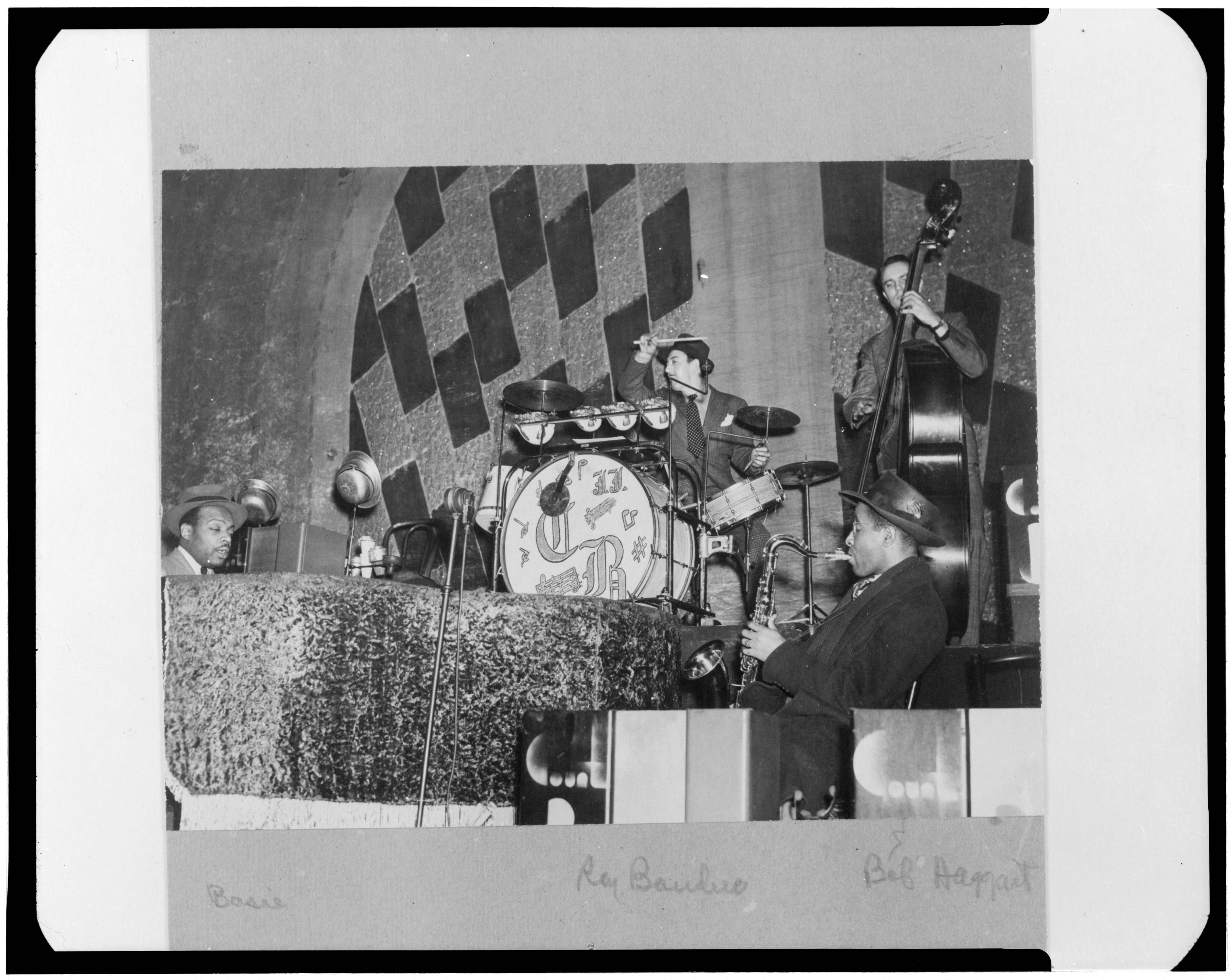

Count Basie

Gregory Gym

March 21, 1941

Count Basie, around 1941

William P. Gottlieb Portrait of Count Basie, Ray Bauduc, Herschel Evans, and Bob Haggart, Howard Theater, Washington, D.C. United States, 1941. Monographic. Photograph.

Fayard Nichols

Dancer with the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band

Tour in the South and Texas

1945

Dizzy Gillespie Big Band, 1946-1948

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Dizzy Gillespie, New York, N.Y., Between 1946 and 1948. United States, 1946. Monographic. Photograph.

James Moody

Saxophonist with the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band

Gregory Gym

December 14, 1946

James Moody (tenor saxophone), with Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet), 1947

William P. Gottlieb, Portrait of Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody, and Howard Johnson, Downbeat, New York, N.Y., ca. Aug. United States, 1947. Monographic. Photograph.

Notes

- Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff (eds.), Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya: The Story Of Jazz By The Men Who Made It (New York: Penguin Books, 1962), 316. ⏎

- Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya, 318-19. ⏎

- Ira Gitler, Swing to Bop (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 16. ⏎

- Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress (New York: Da Capo, 1976), 85-86. ⏎

- Stuart Nicholson, Reminiscing in Tempo: A Portrait of Duke Ellington (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000), 160. ⏎

- Reminiscing in Tempo, 160-162, 165. ⏎

- Benny Goodman and Irving Kolodin, The Kingdom of Swing (New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1939), 185-204. ⏎

- Music is My Mistress, 87. ⏎

- Count Basie and Albert Murray, Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie (New York: Da Capo, 1995), 244-247. ⏎

- Dizzy Gillespie and Al Frazer, To Be, or not … to Bop (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2009), 228-229. ⏎

- To Be, or not … to Bop, 269-270. ⏎