Gene Ramey: A Snapshot of Music in East Austin between 1910 and the early 1930s

In 1978, Gene Ramey sat down and spoke about his life with the writer Stanley Dance for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Project. This was his second interview for the Smithsonian; the first had occurred the year before with Nathan Pearson and Howard Litwak.1 By this point, Ramey was a legendary bassist, having played in the crucial territory Swing groups of Jay McShann and Count Basie as well as in the early groups of modern jazz pioneers Thelonious Monk, Horace Silver, Miles Davis, and Sonny Rollins. Dance’s interview would ultimately end up at the Rutgers Institute for Jazz Studies and Dance made extensive use of it in his book, The World of Count Basie.

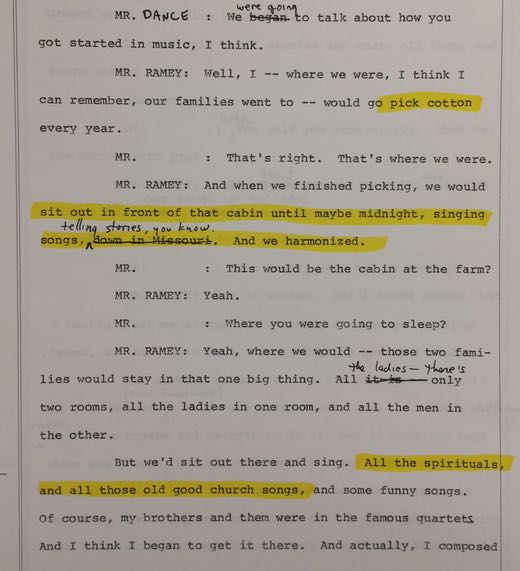

Here, Ramey discusses the presence of music in the home and its relationship to work. As a child, Ramey’s family, as he explains here, would pick cotton somewhere outside the city. The bassist was born in 1913, so this was probably in the mid-to-late teens, a period when African Americans were beginning to leave Austin for work in larger, more industrial cities. Many migrated to the growing oil metropolises of Texas, like Houston and Dallas, but significant numbers also moved North to Chicago or New York as part of the first Great Migration. Soon afterwards, African Americans would stop being the major source for labor for cotton in Central Texas, as new migrants from Mexico began to take their place in the 1920s and 1930s.

Interestingly, Ramey does not discuss song during work—as much literature about black vernacular music does—but after it. Music was a key part of post-labor leisure for his family. In a crowded cabin (two families in a two-room building), they would sit outside, singing songs well into the night. The families shared a repertoire of religious songs—spirituals and probably anthems—but they also amused themselves with comic tunes for fun.

As he notes, Ramey’s brothers were active within Jubilee quartets in Austin (his father and cousins were as well). Jubilee quartets were some of the most popular and most well-respected musical ensembles within black communities across the South during the late 19th and early twentieth centuries. The groups grew out of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a globally famous and influential choir at Fisk University in Nashville. The Fisk Jubilee Singers had pioneered a model of concert spirituals in the 1870s that merged this body of song with the idioms of Western art and choral music: they featured highly composed arrangements and a cappella pure tone singing. In the late 19th century, Jubilee Singers—and the smaller quartet versions—spread to black universities and churches across the U.S. and were often the preferred form of black music for white middle class audiences.

In Travis County, the two most well-known quartets were the Southern Jubilee Quartet and the Exclesior Quartets. Both were tied to black Baptist congregations. The Southern Jubilee Quartet came from Ebenezer Baptist Church and the Exclesior quartet was part of a Jubilee Singers ensemble tied to the St. John Association.

Ramey's brother Joseph sang with the Capitol City Quartet, but it isn’t clear which quartets his other relatives were in. We also know that Ramey’s aunt played piano at Ebenezer. Ebenezer and the St. John Association also had large choirs that were prominent throughout Austin. In 1903, Violet Carrington formed Ebenezer's main ensemble, a choir with 50 voices that became known locally for its highly-trained choral work. In the late 1930s, the group began weekly broadcasts on KNOW as the “Bright and Early Choir,” led by Virgie Carrington DeWitty, Violet Carrington’s daughter. The St. John Association—which was originally formed in the Wheatsville freedman community (now West Campus) after the Civil War--also organized the St. John Jubilee Singers, which played benefit concerts at UT and for the white community in order to collect money for their orphanage and school (now the area occupied by the Highland Austin Community College campus).

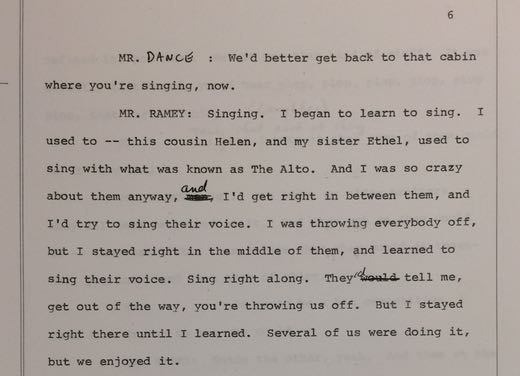

Ramey's family shows how the home could be a place to learn and practice playing with others. Singing a cappella (he does not mention instruments) like this in a group would require one to be able to harmonize with others by ear. In such a setting, one learned to adjust the sound of one’s voice to compliment others. Such situations trained Ramey to perform by hearing others and knowing which sounds fit.

Ramey’s interview gives us a sense that this sort of family-centered song was quite common in Austin’s black community. He remembers that, when they sang in the evenings, they were often surrounded by others doing the same in the distance.

Religious music was not the only thing played in the home. Ramey’s mother, although not trained, had learned, we assume, to play the organ and sing through listening to family or to other musicians in public. In addition to spirituals, hymns, and comedy songs, there were also old time English ballads, poems, and reels. His father and grandfather seemed to gravitate towards string music, playing fiddle and banjo.

This discussion gives us a sense of how far the sounds of religion permeated Ramey and his family’s musical life. It was reflected not just in the types of songs that his extended family sang, but also the way he approached interacting musically with his brothers. Spontaneity, ecstasy, and individual-group interaction were at the center of his church experience and its dynamics gave young Ramey a model of how to improvise against a composed background. As he describes here, his brothers would break into song around the house and Gene, the youngest son, would mimic a preacher, spontaneously commenting and riffing off the music they created.

For Ramey, these camp meetings resonated throughout his life and he heard it in the playing of musicians he met later on. He believed that the sounds and ethos of Holiness music carried on into the territory big band music of Kansas City during the 1930s and 1940s. For him, the music of Count Basie and Jay McShann, both of whose orchestras he played in, had a similar type of freedom and spontaneity. The bands did not perform a great deal of pre-composed and arranged music, but would play along spontaneously with short melodies made up by a band member.

This sort of freedom and feeling wasn’t exclusive to Kansas City bands, it seems. Ramey participated in a similar style of band performance in Central Texas before he departed in the early 1930s for Missouri. In another oral history in 1980, he describes the groups he played in in Austin—Sammy Holmes’s orchestra, George Corley’s Royal Aces —as similarly riff-based, improvisational groups.

We are used to thinking of the blues as a distinct and individual genre of music, but this type of conceptualization is something that came to be over the course of the twentieth century. It isn’t clear what exactly Ramey means by the blues here, however. The blues can be both a song form and a wider set of performance practices. The song form—a chord structure and lyric pattern--was first developed in black vaudeville across the South around the turn of the century. After its initial emergence in theaters and tent shows, composers and performers began to turn it into a consistent compositional structure during the 1910s and 1920s.

We can only speculate on what exactly Ramey meant, but it is reasonable to assume that he is pointing to how Sergeant Willis performed his songs, not the compositions. In this sense, the blues that he says were present all over East Austin were vernacular performance practices of the black community, handed down over decades. Music historians like Thomas Brothers have identified the blues in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a “set of gestures and a feeling of how to place them…shades of phrasing, precise effects of timing, meticulous bending of pitch at the right moment in the right way, judicious distribution of growls and distortions of timbre, all of it wrapped into linguistic dialect and pronunciation—these are the markers of skillful blues.”2

The blues of Sergeant Willis most likely represented musical practices that freed people had brought with them to Austin from Texas slave plantations. These African American styles were never isolated, but were an evolving dialogue between African-derived musical idioms with other forms of American, European, and Latin American music. This vernacular music background included rich vocal styles, ways of “ragging” or syncopating the rhythm of a song, and “blue notes.”

Ramey’s memory of his sisters' fascination with records is a case in point. His siblings are a good example of the way that records, along with community and family, provided models for performing. Recorded music didn’t just provide an awareness of the new voices of America, but offered a way to learn by imitating 78 rpm discs over and over again.

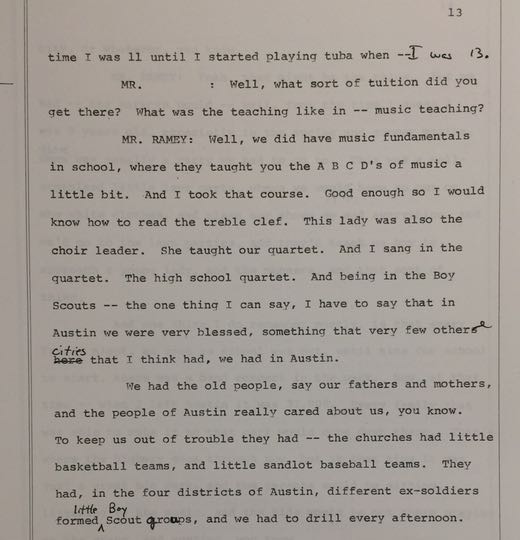

There wasn’t just the informal music of ukulele players in the streets and green spaces of black Austin. Ramey recalls that there was a brass band concert in East Avenue Park (now I-35) every Friday night during the summer. East Avenue, the dividing line between African/Mexican American and Anglo Austin, was itself segregated. Although parks ran up its entire length, the city restricted African Americans to a specific section of the larger park.

Brass and military wind bands were some of the most popular ensembles in America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For decades, they provided a great deal of the music that could be found in open-air public. John Phillip Sousa, who is still remembered as an icon of the American Victorian period, was the most famous bandleader in country during his day. One usually thinks of military marches in connection with these groups, but their popularity was linked to their versatility. The played a wide range of popular and light classical repertoire, from ragtime pieces and cakewalks to opera overtures.

East Austin’s brass band seemed to have been central to its public life, for its concerts were a centerpiece of summer weekends. The ensemble most likely drew formally trained local musicians who were not full-time professionals, as exemplified by the barber who gave Ramey his only formal lessons in Texas. All African American brass bands were common in the South and they played a key role in American pop music history. The scholar Thomas Brothers argues, for example, that the earliest jazz developed from black brass bands adopting vernacular blues practices to their instruments in New Orleans between 1890 and 1910.3

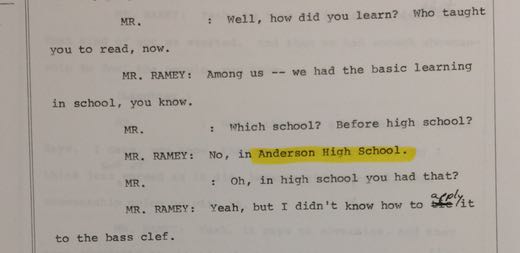

Anderson High School was another source of music education. As Ramey explains, the public school was a major places for formal training for African Americans. At Anderson, students learned how to read music and got the basics of theory. If the family and the streets were the place to learn the subtleties of vernacular practices, the teacher in their segregated high gave African Americans much of their basis in European harmony and melody.

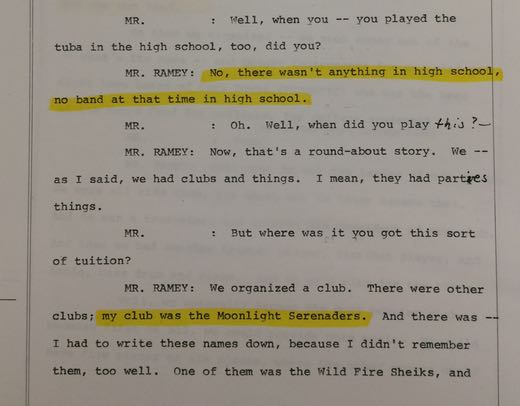

Because of Jim Crow segregation, African Americans were excluded from the vast majority of dance band concerts in Austin. Most orchestra from the 1920s through the 1940s performed for university students at the Stephen F. Austin Hotel , the Driskill Hotel , the Paramount Theatre , the Federated Women’s Clubs , and Gregory Gym , all of which banned African American dancers and listeners. In response, African American high school and college students turned to their own community and formed informal social clubs. These clubs—which adopted names like the Mystic Knights and the Entres Nous Social Club—would organize parties for other black youth at local venues, like the Paradise Inn , the Royal Auditorium (later the Cotton Club ). For these parties, they would hire a local dance band or, as Ramey’s group did, form one of their own.

This may have been how some of the local African American dance and jazz bands of the 1930s got their start. Karl Downs, who led Ramey’s Moonlight Serenaders between 1930 and 1933, took the group into the colleges around the time that Ramey left for Kansas City. Downs was a graduate of Sam Huston College (he became its president in 1943, in fact), but he formed bands associated with Tillotson College in 1933: Karl Downs’ Dragonians (the Dragons was the Tillotson mascot), Karl Downs’ Serenaders, and Karl Earle and his Tillotsonians.

Musicians from other parts of Texas, and possibly the South or Southwest, brought other regional or individual styles of playing into the Austin environment. Herschel Evans, who Ramey remembers playing in Austin in the early 1930s, was from Denton, Texas, but became famous as the tenor sax counter-voice to Lester Young in Count Basie’s classic orchestra. Evans was one of the major saxophone voices of late 1930s Swing and his hard-driving attack was a key part of the influential Basie sound. Likewise, Buddy Tate, who grew up near Dallas and replaced Evans in the Basie band in 1939, was around in Central Texas during this period. Tate and Evans are typically placed as major representatives of the “Texas Tenors,” a unique saxophone sound that developed in Texas in the 1920s and 1930s. Its characteristic squeals and high screeches, a staple of big band music in the 1940s, eventually became the model for Rhythm and Blues and Rock and Roll saxophonists in the 1950s.

Notes

- A transcription of the interviews are in box 2.325/C102 in the Gene Ramey Collection at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. ⏎

- Thomas Brothers, Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 62. ⏎

- Brothers, Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans. ⏎