Paul Whiteman and Duke Ellington, 1936

The final months of 1936 were a special early moment for jazz and dance band music in Austin. Within a period of about seventy days, two of the most celebrated and influential figures in contemporary popular music came to UT: Paul Whiteman and Duke Ellington . Unlike most of their contemporaries, these two bandleaders' significance has survived to the present day, although they tend to occupy opposite positions in most jazz histories. Whiteman, probably the most famous pop celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s, is now typically derided as a self-promoting middlebrow and cultural thief. Since the 1950s, historians and critics have often characterized him as an opportunist who claimed most of the financial benefits of the “jazz craze” while attempting to purge the music’s most obvious connections to African American music. Conversely, Ellington, who was also a leading figure during roughly the same period, has remained one of the most iconic symbols of jazz authenticity and brilliance.

When they played in Texas, both bandleaders were far from home—they were both eminent cultural citizens of New York, the home of the music industry. Their appearances in this other capital, considered a civilizational backwater by most of the country at the time, was not coincidental. They had both been contracted for a much larger and well-funded event, the Texas Centennial Exhibition in Dallas. A large-scale and highly planned celebration, the exhibition tried hard to define the Lone Star state to the rest of the nation as more than just cowboys, tumbleweeds, and oil derricks.

The Dallas exhibition’s ability to draw major acts provided opportunities to nearby University of Texas. Ellington played at the Centennial for three days in October, including during a segregated 'Negro Day,' while Whiteman played for months at the Casa Manana in Fort Worth's centennial festivities. Their proximity allowed UT to draw both down to the capital. Despite their similarities in stature, Ellington and Whiteman were treated very differently by powers that be in white Austin, however. Whiteman drew the maximum amount of prestige and respect; Ellington, on the other hand, was largely treated as just another black entertainer passing through the city.

Examined closely, these two concert reveal a great deal about music in Austin before World War II. Comparing the two concerts highlights many of the major contexts, ideas, debates, and inequalities that surrounded jazz and dance in the 1930s and 1940s. Ellington and Whiteman’s appearances at UT reveals many of the ways that Austin—and national—audiences thought about jazz and art. At the same time, it shows how racism shaped the way bandleaders were treated and the conditions under which they performed.

Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra

Hogg Auditorium, September 30, 1936

Whiteman’s late summer concert in Austin was something of a spontaneous, ad hoc affair. It was not meticulously planned, as one might expect for a university concert by one of biggest stars in American music. In fact, his appearace was a last minute favor and gesture of gratitude to the Texas govenor.

Whiteman's performance at UT was an act of noblesse oblige for the grandiose recognition and accolade that the state had just bestowed on him. The previous Saturday, Governor James Allred declared September 26 through October 3 “Paul Whiteman Week in Texas.” Occuring during the state's centennial year celebrations, it was an outsized honor for a man who was born in Denver, had made a name in San Francisco, and now resided in New York City. Most likely, the govenor wished to weld some of Whiteman's immense national celebrity to state's annivesary festivities. Allred announced the official Texas week in “recognition of the outstanding accomplishments in the field of music by America’s so-called ‘king of jazz.’”1

Whiteman waived his normal $2700 fee, but he refused to take on any of the expenses associated with his performance. He insisted that someone pay for his travel, a tab that was eagerly picked up by D.C. Reed, an Austin businessman. Reed, who declared that any leftover money from ticket sales become a donation to the Texas Memorial Museum fund (itself a Texas Centennial project), underwrote a special train from Fort Worth to Austin and back.

The concert brought together the major centers of power in Austin: it was a joint endeavor by the university, the state government, and the business community. Because of the short notice, tickets only went on sale the afternoon before Whiteman appeared. Even so, The Daily Texan expected there to be a shortage of seats. Only about 3/4 of the hall went on sale: 1000 tickets were available while the remaining 350 places were given to state officials.

At 1 am on the day of the concert, Whiteman and his band left Fort Worth, coming straight from a show that had begun the previous night. After many hours of red-eye travel, they pulled into Austin at around 8 am. From the start, the “King of Jazz” was treated like a visiting dignitary. When his train chugged into the station, a select group of Austin's political and financial elite were there to greet him: two Texas senators (Holbrook and Rawlings); two representatives (Colquitt and Kanetsch); D.C. Reed, who underwrote his trip; Dr. Goodall Wooten, the President of the Chamber of Commerce; Walter E. Long, the secretary of the Chamber of Commerce; and Dave Reed, the City Manager, stood in the chilly morning air to welcome him.

Whiteman, it seems, did not consider such a greeting worthy of much notice. He slept in his car and left the city's prominent personalities waiting for him on the platform. As the Austin Statesman put it, they “literally but good-naturedly cooled their heels in the fall breezes outside his pullman.” Reportedly, Senator T.J. Holbrook suggested that “somebody really out to tell him it's time to get up.” D.C. Reed agreed but, was worried about upsetting their guest and replied, “A good idea, but let somebody else set off the alarm clock.”2

Once he finally appeared, Whiteman was whisked around from celebration to celebration with a police motorcycle escort. First, he went to a breakfast at the Delta Chi fraternity house on Rio Grande St. in West Campus. Apparently, Whiteman was as famous for his size and appetite as he was for his music. Conversation around the table turned to his weight and he claimed that he hadn't gained any pounds in Texas, opening his coat to reveal his blue and tan belt. “See? You can tell by the notches that I’m holding my own,” he declared as he ate scrambled eggs, beaten biscuits, sausage cakes, and coffee.

At lunch, Whiteman spoke briefly and episodically to student reporters from the Daily Texan. Apparently “Mr. P.W.” was generally tight-lipped, but spoke avidly about Goodall Wooten’s gun collection. Impressed by the contrast between Wooten’s house and his antique weapons, he quipped, “they take you into a house that is modern and show you a gun that was made in 1375.” Otherwise, Whiteman talked about losing weight (“if you want to reduce, just get a good paint pony and ride out over all the prairie you can find”), the popularity of swing in the mid-1930s (“sweet swing, hot swing, low swing, high swing, everybody is swinging”); and collecting Texas melodies (“I have received a number of songs from Texas for my folklore collection”). At the end of the interview, the Daily Texan jokingly offered him a job as a reporter, to which he claimed, “it’s more than I deserve” and absurdly signed the number “30” to a piece of yellow copy paper.

Whiteman and his musicians then walked a very short distance from the the Texas Union luncheon to Hogg Auditorium . The concert began at noon, shortly after a class had been cleared from the building. The hall was close to, but not entirely, full: 1250 people came to hear the famous orchestra, leaving 100 seats empty. In addition to around 1000 students and hundreds of legislators, the audience included Governor Allred; UT President Benedict; W.L. McGill, head of the University Centennial; Goodall Wooten; and Louis Goldberg, Chamber of Commerce Vice President.

During their one hour concert, Whiteman’s orchestra played a wide variety of material: “symphonic arrangements, popular arrangements, some of the Texas songs, several of Whiteman’s own arrangements, and some typical American jazz hits.” One reporter described the concert program as “characteristic of the Jazz King’s style, unusual in arrangement and typical of the modern ‘swing’ tempos, modulated by the influence of Whiteman’s good taste in music.”3 Whiteman’s orchestra was not the only group of performers, however—he had brought with him a huge variety show, which also included a vocal quartet, “hillbilly” comedians, dancers, female vocalists, and a star trombone soloist from Texas, Jack Teagarden.

After their relatively brief performance, Whiteman and his troupe were gone. They packed up, left Hogg, and returned to the station, where his special promptly departed for Fort Worth. Once back in North Texas, the group did their second performance of the day, playing their regular gig at the Casa Mañana.

Despite their hasty departure, Whiteman had clearly made a close connection to the Governor during his trip. The Texas government clearly wished to connect themselves with this larger-than-life giant of popular culture. It did not take him long to return: he was back in Austin three and a half months later to perform at Allred’s Inauguration Ball. Allred’s gubernatorial celebration was split amongst three venues—Gregory gym , the Driskill hotel , and the Stephen F. Austin hotel —and three different bands, but pride of place was given to UT campus, the gym, and Whiteman.

Whiteman in his colonel uniform with Governor Allred, 7/17/1937

Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries

When he appeared again in Gregory, on a stage filled with green branches, large fake roses, and shining globes, he displayed a new honor. Allred had named him a special colonel to the Governor and the bandleader conducted his band in a wine colored uniform. The floor of the gym, which was filled to the brim, shouted in approval.4 At some point in the night, Whiteman returned all the university’s favors, allowing Jimmie Valentine, a UT student, to sing several songs with the world famous orchestra.

Duke Ellington and his Orchestra

The Texas Union, November 26, 1936

Duke Ellingon and his band also travelled to Austin in a special coach, but he had to book and pay for it himself. An individual train was arranged by others just to bring Whiteman from Fort Worth to Austin—for his convenience and comfort. In contrast, Ellington paid for a private Pullman car out of necessity, a strategy to head off some of the most egregious forms of racism and discrimination as he moved through the Jim Crow South.

Ellington also came from the Dallas-Fort Worth area, but unlike Whiteman, he was on a long and arduous tour. Before Dallas, he had been in St. Louis, Kansas City, Memphis, Charleston, Baltimore, and a host of other cities and towns. Ellington’s Dallas stay between November 10 and 16 was his second trip to the city in the last two months (he had played at the Texas Centennial in October). In November, he performed at the Chez Maurice, an elite nightclub. While there, he was treated like as a star by local bigwigs and musicians. Many of the top white territory bandleaders came to pay hommage--Bob Crosby, Joe Reichman, Gus Arnheim, and Horace Hight--and at least one local businessmann, the wealthy hotel owner Will Morrisey, stopped by to visit with the Duke.

After months on the road, he arrived in the Austin on November 21st, five days before his dance at UT. The university gig was his last date in the capital; he, in fact, played multiple concerts while in the Austin area. The first was at the Stephen F. Austin hotel on the 21st. This formal, put on by Kappa Sigma fraternity, was in the open air rooftop garden, overlooking Congress Ave. For most of this middle Fall evening, Ellington's music must have floated around passersby on the city's major business and political thoroughfare. Above these pedestrians, the band played in a simultaneously glitzy and verdant scene. The frat made themselves the focus of the party's decorations: most of the staged scene was drenched in scarlet, white, and green, the group's official colors. Perhaps emphasizing the primitivist “jungle music” trope that surrounded Ellington’s band during their famous tenure at Harlem’s Cotton Club in the late 1920s, the hotel’s roof was filled with shrubs and vines, “simulating a garden scene.”5 Behind the band were gold-wrapped pillars wrapped and gold drapery. Luckily for other Austinites, this concert was broadcast. The city’s only radio station at the time, KNOW , live broadcast their dance at 10 pm.

The orchestra’s other full time dances were all for students at The University of Texas and Texas A&M, the major white collegiate rivals of Central-East Texas. Ellington provided the music for the two competitors' major yearly ritual, the Thanksgiving football match. The orchestra first played for a Town Hall Program and regimental dance at A&M on the evening of 24th. Two days later, after the game (which some of the musicians watched), the group played at UT's Texas Union for a formal Turkey-Day ball. UT students were clearly immense fans of Ellington—2000 tuxedoed and gowned co-eds came out, 37% more than attended Whiteman’s concert a few months before. The size of the crowd prompted Charles Zivley, the manager of the Union, to open up a second ballroom, so that dancers could listen to the band on a PA system.

Ellington’s Union concert was a important Austin musical event: in its ballroom, he premiered his composition “Black Butterfly.” He also made an important gesture to the city’s black community by performing a composition by a local African American composer, “Lost Ecstasy” (Louis Mitchell). Furthermore, Ivie Anderson, the group’s vocalist, sang lyrics for “Black Butterfly” and “Lost Ecstasy” written by B.F. Carruthers, a professor at Tillotson College. Students filled the floor to dance, but many were clearly enthralled by Ellington and his band. They “cluster[ed] about the bandstand as Duke scored a tremendous hit.” Anderson’s singing also thrilled the audience and she “scored several times with her humerous and coquettish interpretations before the mike.”7

Atypically, the UT dance included a few African American members in the audience. Mitchell, the composer of “Lost Ecstasy” and a friend of Ellington’s, and his wife were allowed to attend, as were Mr. and Mrs. Howard Alexander (as guests of Ivie Anderson). Even with the presence of a few prominent members of the black community, the UT students seemed to have avoided any racist antagonism or misbehavior. Carruthers, who was also a correspondent for the Chicago Defender, reported that “several members of the band commented on the courtesy and excellent behavior of the white student body.”

The following day, the band raced to Houston aboard their Pullman to play for the Junior League in the City Auditorium. After that, they left for West Texas, where they played Pecos, before moving on to New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, and California.

Ellington and Whiteman, Entertainment and Art

The Whiteman and Ellington concerts occurred in the middle of a remarkable shift in the status of jazz and big band music. Historians have argued that audiences and critics began to hear these forms of popular music as something more than just entertainment during the 1930s and 1940s. This was a major change. Since the late 19th century, Americans had seen popular music as the opposite of art music. Pop was considered crass and commercial, created for the market and thus held little aesthetic value. It was also seen as quintessentially American, while classical music was decidedly European. How audiences enjoyed pop music played a key role in its lowly status—people danced to it or were impressed by its weirdness and novelty. Concert music, on the other hand, was listened to attentively by a seated group of connoisseurs. For most of American society, jazz was the antithesis of culture8

But this strict division between classical and popular music started to break down during the 1930s. People began to listen more intently and appreciate the quality of big band arrangements, paying attention to the sounds of Benny Goodman and Jimmie Lunceford in ways that people had previously done to the works Handel or Beethoven. This was especially true of the Swing bands, which often hired arrangers with training in classical composition. Audiences still primarily danced to the bands of this period, but they also appreciated the complexity and skill of its compositions and improvisations.

That the art/popular divide was starting to wither was most visible in Carnegie Hall, one of the country's revered temples of high culture. In 1938, Benny Goodman and his orchestra performed there with members of Count Basie and Ellington’s bands. Later that year, Louis Armstrong sang in its hallowed halls with the Whiteman ensemble. In 1943, Ellington finally stepped onto its stage and introduced what was probably his largest, most symphonic work, the three part, forty minute Black, Brown, and Beige.

That Duke Ellington and Paul Whiteman had been part of the ground-breaking concerts in Carnegie Hall was not a coincidence. They had been two of the most important and influential figures in this transition for more than a decade. They had been performing music that emphasized complex compositions and rich arrangements since the 1920s and they had marketed themselves as more than just a background for foxtrots or shimmies since the beginning. Whiteman was one of the pioneers of the modern dance orchestra—he expanded the scale of the pop ensemble and consciously attempted to “raise” the level of jazz. Wishing to create a fusion of concert and popular music, he hired Ferde Grofe, a concert composer, to write and arrange his music.

Whiteman’s goal was to create a new fusion of African American folk and European art music. In this “symphonic jazz,” he imagined himself as taking an unpolished, unsophisticated raw material—jazz—and raising it up to a new level, inventing the modern music of the American twentieth century. While giving some credit to its black origins, Whiteman had a considerable bias. He considered the earliest jazz to be primitive and believed the music required the hand of an innovator to elevate it into something higher. His 1924 “Experiment in Modern Music” at Aeolian Hall exemplified his vision: he began with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band’s “Livery Stable Blues” (the first jazz recording) and ended with a piece he commissioned for the concert, George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”9 The concert was meant to show how far the music had come, from New Orleans to New York.

Ellington believed the music he made—and the musicians who played it—were more than just entertainment. As early as 1930, Ellington was already arguing that “what is still known as ‘jazz’ is going to play a considerable part in the serious music of the future… what we know as ‘jazz’ is something more than just dance music.”12 A few years later, he was hailed by the critic R.D. Darell and compared to the major modern composers: he described him as a “pianist, composer, and orchestra leader, gifted with a seemingly inexhaustible well of melodic invention, possessor of a keenly developed craftmanship in composition and orchestration.”13

His musical aspirations as a composer could be clearly seen in a number of recordings from the first half of the 1930s: “Creole Rhapsody,” probably modeled on “Rhapsody in Blue,” and his 1935 piece “Reminiscing in Tempo,” an incredibly ambitious 13-minute composition (it took up four record sides) of great harmonic and melodic richness.14 And, like Whiteman, Ellington was an internationally famous figure by 1936. Since beginning his radio broadcasts from the New York Cotton Club in 1928, he had become probably the most popular black bandleader in the country.

Paul Whiteman’s performance in Hogg Auditorium represented the ways that the strict divide between entertainment and art had begun to be blurred by the mid-1930s. Hogg was the premier place for high culture performances at UT in the 1930s: it was a formal space, with a seated audience, where things like theater, chamber music concerts, and philosophy lectures happened. Whiteman’s performance there was a sign that a popular music orchestra was considered worthy of a concert hall and an audience of political and business elites. Similarly, Ellington performed and gave a speech in the chapels of Samuel Huston and Tillotson college, activities typically reserved for professors, clergy, jubilee quartets, and classical musicians. For African American communities, the division between the sacred and the profane/popular was another meaningful boundary, a line that Ellington clearly traversed on his visit to Austin in 1936.

Race and Art

The fact that Whiteman performed in Hogg and Ellington in the Texas Union also highlights the way that art and entertainment were still deeply correlated to race. UT was willing to confirm Whiteman’s aspirations to be more than entertainment and bring him into its most elevated venue. For Ellington, it would not. Elllington—like Whiteman, one of the most famous and ambitious bandleaders of the day—appeared only as a dance band for white audiences: in the Union ballroom and on the roof of the Stephen F. Austin hotel for a frat party. Ellington and his band were black; Whiteman was white. Ellington’s music was for dancing; Whiteman’s for listening.

It should be noted that Whiteman's performance in Hogg was indeed exceptional. Other contemporary white bandleaders—like Vincent Lopez or Guy Lombardo—did not play in Hogg either. But, in other ways, Ellington was a peer to Whiteman in ways that these other leaders never were, nor tried to be. Ellington’s music, like Whiteman, set itself out to be more than dance or popular music. Whiteman himself recognized this—he included “Creole Rhapsody” in his “Fifth Experiment in Modern Music” at Carnegie Hall in 1933 and commissioned Ellington to write “Blue Belles of Harlem” in 1939. Nor were Ellington’s ambitions obscure: since the early 1930s, Ellington’s manager, Irving Mills, had specifically marketed the bandleader as a composer of great stature and a master of modern music. In his “Advertising Manual,” Mills instructed all of Ellington's press material to “sell [him] as a great artist, a musical genius whose unique style and individual theories of harmony have created a new music.”15 And it was not just Mills, but critics and newspapers across the country who characterized him as a notable creator. In 1933, for example, the Dallas News referred to him as the “African Stravinsky.”16 Even after Ellington made his most complex and wide-ranging work, “Black, Brown, and Beige,” and played at Carnegie Hall in 1943, UT continued to book him as a dance band in the gym or Union.

The power centers of the city also treated the two bandleaders quite differently. Austin's elite did everything they could to ingratiate and publicly connect themselves to Whiteman during his visit. Ellington, on the other hand, was not greeted at the station by politicians and the Chamber of Commerce, brought to the capitol building, or given a luncheon. His dances and presence did not register on the calendars of state politics or the university administration.

Whiteman and Ellington’s coverage by the local press followed a similar pattern. The Daily Texan, Austin American, and Austin Statesman wrote numerous articles about Whiteman and made every attempt to give him a prominent voice through interviews, even though he was only in the city for less than six hours. Taken together, the person of Paul Whiteman comes across in great detail: his demeanor, his biography, his performance style, and his words. Ellington was in town for five days and appeared at least seven times, but he was not always featured prominently. In the article about his first concert at Stephen F. Austin Hotel, for example, he doesn’t even make the headline, “Fraternity is Host for Fall Formal Dance.” One has to read the second paragraph to even realize that the band playing for the Kappa Sigma party is the Duke Ellington orchestra. The Daily Texan did publish an article about Ellington and his background, but many of their other articles similarly emphasized the dance and not the performer.

Ellington was treated radically differently by Austin’s African American community and the national black press, however. He was hosted by the black educated elite of the university and welcomed as a major figure and composer. While in Austin, he connected with the major institutions in black life: the universities, a church, and the public schools. At Tillotson College, he lectured on the serious purpose of his music; at Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, he was the centerpiece of a benefit; and when he played at Kealing Middle School, he was presented as a model of African American achievement.

Throughout his visit, East Austin greeted Duke Ellington as what was known at the time as a “Race Man,” a figure who embodied the possibilities of great deeds and dignity in the face of a racist and skeptical America. But none of this was in the Statesman or Daily Texan. Black readers had to look to a newspaper from Illinois to see anything about Ellington’s important visits to their middle school, their colleges, and their church. Like Whiteman’s trip in the white Austin newspapers, Ellington’s stay in Central Texas was covered in detail by one of the major black newspapers in the U.S., The Chicago Defender.

Ellington and Whiteman’s visits in 1936 were surrounded by a larger urban process: the completion of the city’s Jim Crow segregation. Austin city officials and residents had begun to use municipal ordinances and state laws to ban African Americans from sharing spaces and instituions with whites since the beginning of the twentieth century. By the 1930s, the city was almost entirely divided into black and white sections of the city. This was a profound change in the city: in the late 19th century, African Americans had lived and gone to schools across the city; by the time of these concerts, almost all African Americans and their segregated institutions were congregated in East Austin.

These two sets of concerts reflected the way that Austin carved out a line between its black and white residents. One of the main points of segregation was to make it clear and constant that black Austinites were a denigrated undercaste: to treat them differently from their white fellows residents and exclude them from participation in mainstream Austin society. Pushed together as a group, African Americans created a community and social life that revolved around black-controlled places: churches, schools, bars, restaurants, and shops.

The city welcomed Whiteman as a cultural ambassador, a man of great stature and accomplishment that deserved to be recognized and celebrated by all local elites. He performed in one of the most esteemed venues in Austin, Hogg auditorium on campus, and appeared for an entirely white crowd. He left without ever having contact with East Austin. Ellington, on the other hand, was only given access to white society as an entertainer, on the stage on a hotel roof for a frat dance and for a campus dance building to celebrate a football victory. East Austin, where he stayed and socialized, hailed him as one of the great creators of the moment. He made appearances across the black community and his presence was treated as a major event.

The Myth of Texas

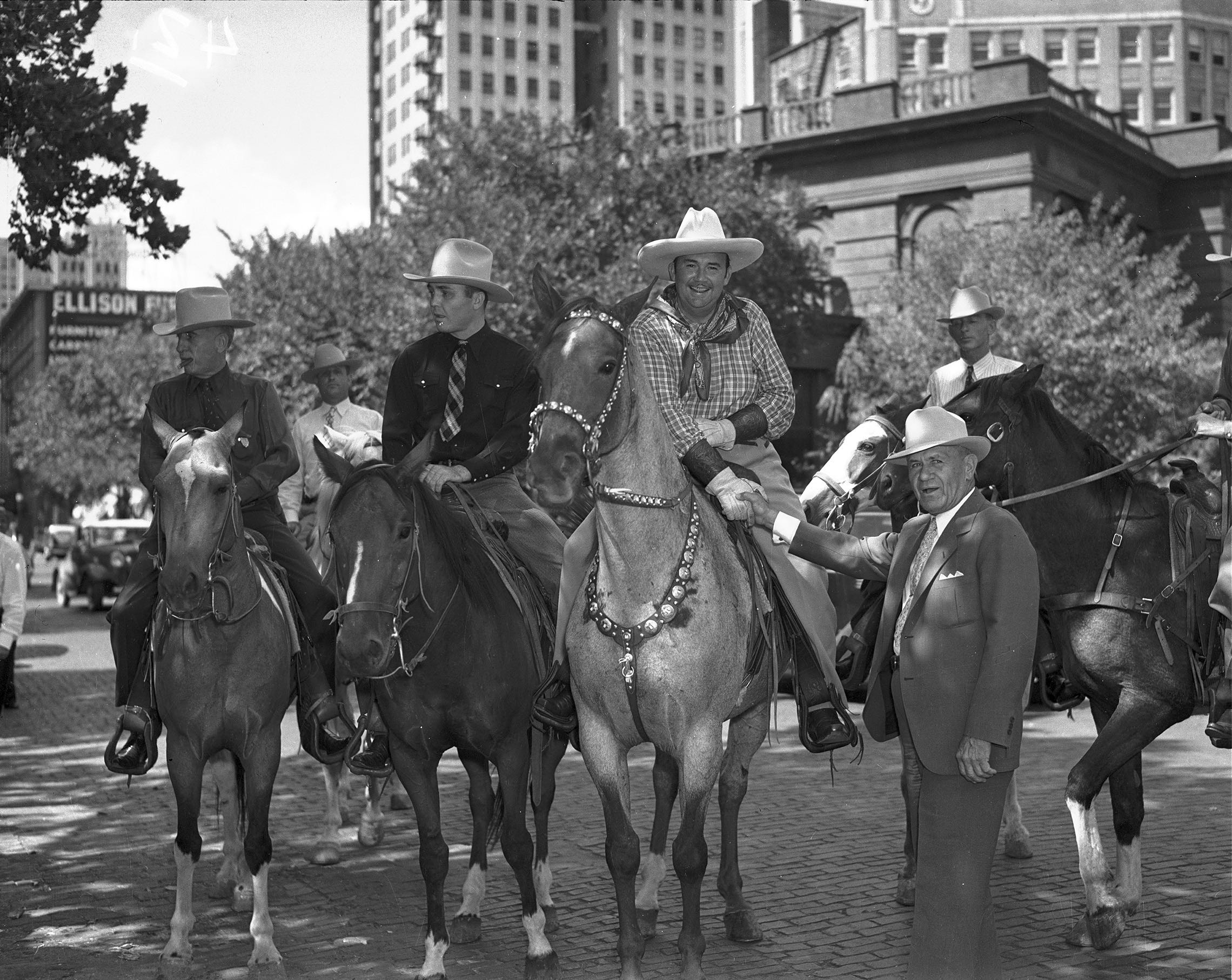

Ellington and Whiteman also seemed to have responded to the peculiarities and aura of Texas in different ways. While performing in Fort Worth in 1936, Whiteman became fascinated with the “Western” atmosphere of Texas. He imitated as much of a cowboy lifestyle and aesthetic as he could: he lived on a ranch outside the city and spent a great deal of his spare time buying and riding horses. Treating it as exotica, he bought up artifacts to take back with him to New York: saddles, spurs, and ranch equipment. Whenever he appeared in public, he wore a cowboy hat, boots, and a Western necktie.

Paul Whiteman Day in Fort Worth, shaking hands with mayor, 9/1/36

Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries

From the few written accounts of his trip to Texas that remain, Ellington seemed to have responded to the peculiarities of Texas with more ambiguity. For Ellington, who was famous for being immaculately dressed, it was not the image of the cowboy that he mimicked, but the accent:

Notes

- “Whiteman Week Set,” Austin American, September 27, 1936. ⏎

- Lorraine Barnes, “Whiteman Holding Own At 2 Fronts-Waist and Music!,” Austin Statesman, September 30, 1936. ⏎

- “Whiteman’s Concert to Begin at Noon in Hogg Auditorium; ‘King of Jazz’ Honors State,” The Daily Texan, September 30, 1936. ⏎

- “Whiteman and Governor Perform Backstage to Amuse Officials,” Daily Texan, January 20, 1937. ⏎

- “Fraternity is Host for Fall Formal Dance,” Austin American November 22, 1936. ⏎

- “Timely Topics,” Chicago Defender, December 5, 1936. ⏎

- “Ellington Plays for Texas U. Prom,” Chicago Defender, December 5, 1936. ⏎

- Jazz article ⏎

- Scott DeVeaux and Gary Giddens, Jazz (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 116-119. ⏎

- Henry Taubman, “The ‘Duke’ Invades Carnegie Hall,” The New York Times Magazine, January 17, 1943 ⏎

- Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress (New York: Da Capo, 1976), 103. ⏎

- As quoted in Graham Lock, Bluetopia: Visions of the Future and Revisions of the Past in the Work of Sun Ra, Duke Ellington, and Anthony Braxton (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 77-78. ⏎

- D.H. Darrell, “Black Beauty,” in Mark Tucker ed., The Duke Ellington Reader (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 59. ⏎

- Terry Teachout, Duke: The Like of Duke Ellington (London: The Robson Press, 2013), 120-124. ⏎

- “Irving Mills Presents Duke Ellington” in Stuart Nicholson, Reminiscing in Tempo: A Portrait of Duke Ellington (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2000), 153. ⏎

- Teachout, Duke, 142. ⏎

- Ellington, Music is My Mistress, 85-86. ⏎