East Austin Centers of Swing: The Royal Auditorium and the Cotton Club, 817 E. 11th

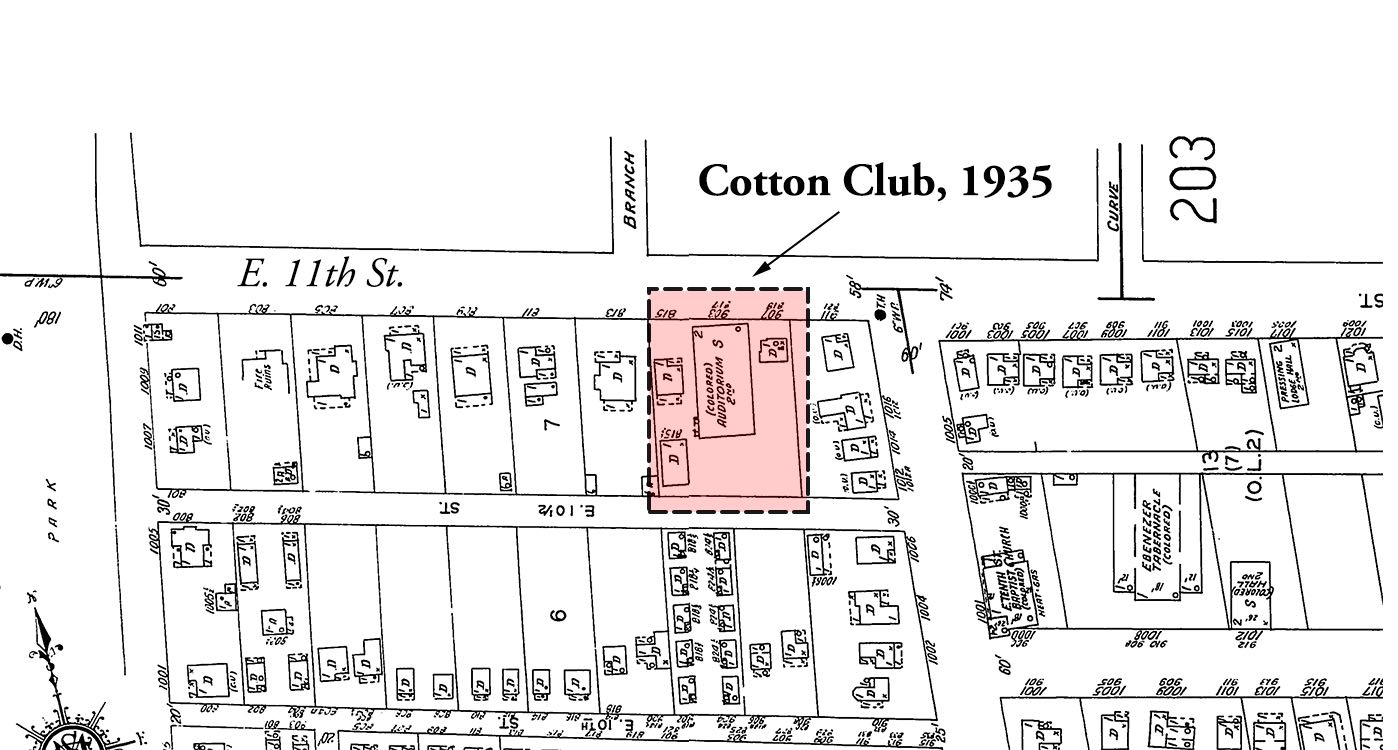

Although rarely remembered today, a long razed building on the edge of East Austin was one of the most historically important places for big band and swing music in Central Texas before World War Two. Situated at 817 East 11th St., just beyond East Avenue, it housed two African American dance halls between the late 1920s and the early 1940s: the Royal Auditorium and the Cotton Club . Although no photographs are currently available, we know it was a large, two story building with an inside balcony. It must have been fairly large, for it reportedly could accommodate between 1500 and 2000 people. Even though it was a purely local music hub, it received national attention when it came under new management in 1938. The Chicago Defender, the largest black newspaper in the country, announced its re-opening and referred to it as “the famous Cotton Club, a $30,000 Austin, Texas Race pleasure house.”1

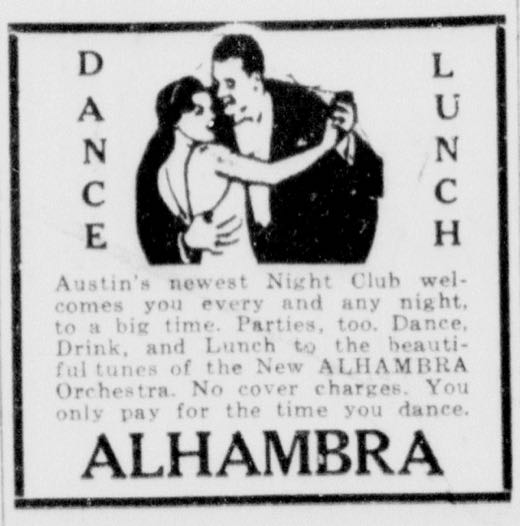

The Alhambra did not last long and the building became the “Cotton Club” in August. Soon after, the city attorney filed an injunction against the owners, Lamar Steen (alias Earl Anderson) and Ed Lee, from operating the club, claiming that they were using it as a gambling house and for illegally selling liquor. Steen was also accused of running brothels out of four lower Congress Ave. hotels. A few days later, Texas Rangers, sheriff officers, and local police raided the hall at the behest of Governor Allred, although no liquor was apparently found. In October, the club came under the new management of G.C. Harber. At some point in 1935—it isn’t clear if it was before the Alhambra or after the Cotton Club opened—the music ceased altogether. The building was briefly repurposed and became the East Austin branch of the Y.M.C.A.2

By the late 1930s, the “Cotton Club” returned to being a primarily black venue. It operated in 1936 and 1937, although there are no records of music being performed there. In 1938, H. Rowlett, the manager of a local booking agency and a “central Texas pleasure promoter,” attempted to make the hall a premier place for touring African American bands. Perhaps hoping to take advantage of the increased attention and appreciation that African American orchestras received during the height of the Swing period, he promptly brought in some of the biggest bands in the country.

The hall was originally black owned (later ownership is not clear) and, through its different iterations, was the main dance music venue in the 1930s and early 1940s for African American Austinites, who were barred by Jim Crow segregation from attending all other “whites only” venues, restaurants, and clubs. Detailed records of who performed there are not available, since the main newspapers in Austin did not consistently cover its performances and there wasn’t a formal black press in the city at the time. From the limited number of advertisements and articles that do exist, it clearly hosted some of the major orchestras of these decades. Local advertising was done by putting placards out across East Austin.3

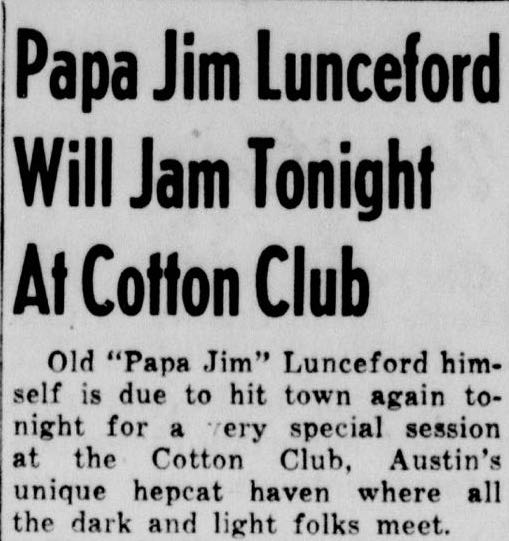

From our sketchy sources, we know that Earl Hines , Louis Armstrong , Don Redman , Lionel Hampton , Erskine Hawkins , and Jimmie Lunceford performed there between 1932 and 1942.4 It is also very probable that Chick Webb and Noble Sissle did as well. Gene Ramey, who left home in 1933, remembered a steady stream of bands arriving in East Austin:

Like UT for white bands, Samuel Huston and Tillotson colleges were probably significant reasons that major black orchestras came to the Cotton Club. The saxophonist Joe Houston, who grew up in Austin, claimed that

Many of these swing-centered bands only appeared at the Royal Auditorium and Cotton Club, but a number of artists like Armstrong and Lunceford played a second show there after being booked for segregated performances at UT’s Gregory Gym or the Paramount Theater . Major dances at the hall could attract huge crowds. During a Louis Armstrong performance there in the early 1940s, for example, the balcony became so overcrowded that it collapsed.7

In this “big ballroom with good acoustics,” there was seating for onlookers. Joe Houston recalled that

In addition to these national acts, local and regional black orchestras, like Don Albert , George Corley’s Royal Aces , Tommie Brooks , Boots and his Buddies , Johnny Simmons , and the Prairie View Collegians , played dances there as well.9 From the incomplete performance records, it is clear that the hall specialized in black “hot” orchestras. The Royal Auditorium and Cotton Club were part of a larger, forgotten network of African American dance clubs in Central, East, and North Texas during the 1930s and 1940s which provided a great deal of work for these Texas Territory and Swing bands. There is only one recorded instance of a white band performing there for a black audience: in 1942, the local group Cecil Hogan and his Swingsters played a battle dance against an unnamed “all star negro orchestra” for a wartime U.S.O. benefit.10

Although it was predominantly a black club in a segregated part of Austin, whites were not barred entry. Thus, it was one of the few cultural spaces in the city where white and black audiences co-existed and saw and danced to the same performances. The Daily Texan described the Cotton Club as “Austin’s unique hepcat haven where all the dark and light folk meet.”11

We don’t have any substantial direct evidence about the interactions of black and white crowds at the Cotton Club. Despite the rope barrier, members of the crowd could see, hear, and possibly interact with one another. Most likely, it gave white listeners and dancers a chance to mimic the style and dancing of their black fellow citizens. We know, for example, that UT brought two jitterbug dance contest winners from the Cotton Club to Hogg Auditorium in 1942 to show off their “radical form of dancing.”13 For whites patrons, the visit was also surrounded by an aura of exciting transgression and racial fantasies of primitive authenticity. One article about a Jimmie Lunceford concert, for example, appealed to its college audience by claiming that “you can expect some real low-down Negro music with no holds barred tonight.” Similarly, Alan Lomax recalled journeying with other UT students in the 1930s to a home in East Austin, where they “risk[ed] expulsion” to listen to Ruby and her husband play “the real blues.”14

White visitors to the Cotton Club in the 1930s were part of a larger phenomenon of “slumming” in the metropolises of the Northeast, West Coast, and Midwest. Beginning in the early 1920s, white middle- and upper-class urbanites began to visit clubs and bars in segregated African American areas within their cities. In response to the Great Migration of African Americans from the South, these patrons sought out the “thrills” of what they saw as other, quite alien worlds from the neighborhoods where they lived. Believing African Americans and their cultural-social life to be primitive, raw, and hyper-sexualized, they drank in black bars and saw black performers in an effort to fulfill their fantasies of freedom and to show off their urban sophistication. In fact, Austin’s Cotton Club was named after the most famous “slumming” venue in the country, Harlem’s Cotton Club, where wealthy whites paid to watch scantily clad African American dancers and listen to what was advertised as the “jungle music” of Duke Ellington. The short-lived Alhambra, in fact, mimicked the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn even more closely by briefly turning it into a white club in East Austin.

For African Americans, the Royal Auditorium and Cotton Club were crucial parts of the cultural and business district of East Austin. As Jim Crow segregation intensified after the 1890s, African Americans across the South built and developed their own separate institutions and businesses, often on a main street through the heart of their communities. For Austin, East 11th street was one of these centers: in the 1930s, it had Samuel Huston College, its dorms, the Cotton Club, Ebenezer Baptist Church (one block off), a Masonic Lodge, stores, restaurants, a bakery, a private school, a pharmacist, and an home for elderly women. In addition to dances, the Cotton Club also hosted basketball games for Tillotson College.15

By 1943, the dance hall had closed down again. At first, in response to demands by African American community leaders, the City Council negotiated to buy and turn it into a recreational building for black servicemen. After inspecting it, they decided to build a new building instead. In 1944, Samuel Huston College, which was located across 11th street, obtained a permit to turn it into a dorm and dining room. That same year, the city began construction on the Doris Miller Auditorium in Rosewood Park , just a ways down the street from the old Cotton Club hall. For the next twenty odd years, this auditorium took over the role that the old dance hall had previously served: it was the segregated music venue for large touring performances for Austin’s black community.16

Notes

- Chicago Defender (March 26, 1938). ⏎

- Austin Statesman (August 13, 1935); Austin Statesman (August 18, 1935); Austin Statesman (October 23, 1935). ⏎

- Eddie Determeyer, Rhythm is Our Business: Jimmie Lunceford and the Harlem Express* (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 193. ⏎

- Chicago Defender (March 26, 1938); Austin American (July 27, 1941). ⏎

- Interview with Gene Ramey, Gene Ramey Collection, Box 2.325/C102, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- Determeyer, Rhythm is Our Business, 146. ⏎

- Daily Texan (December 8, 1942). ⏎

- Determeyer, Rhythm is Our Business, 193. ⏎

- San Antonio Register (August 11, 1933); San Antonio Register (January 12, 1934); Daily Texan (May 6, 1938); Daily Texan (February 22, 1938). ⏎

- Austin American (June 7, 1942). ⏎

- Daily Texan (February 24, 1942). ⏎

- As quoted in Thomas Brothers, Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014), 427. ⏎

- Daily Texan (November 13, 1942. ⏎

- As quoted in John Swed, Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World (New York: Viking, 2010), 21. ⏎

- Austin American (February 14, 1937); Austin Statesman (February 18, 1937). ⏎

- Austin American (May 20, 1943); Austin American (September 17, 1944). ⏎