Western Swing in Austin, Part II: Two Predecessors and a Context, 1930-1942

Austin's thriving wartime and postwar Country scene did not appear out of thin air. Although Western Swing's presence in the 1930s was minor compared to DFW or East Texas, the style was not absent in Central Texas. The Texas capital had its own version of Bob Wills and Milton Brown: Uncle Walt . Walt and his collaborators, active throughout the final years of the Depression, had a limited number of places to play in their early years. Their music would not find a significant live audience until the next decade. There was, however, another unrecognized and more unusual predecessor to the 1940s Western Swing scene in Austin: the collegiate barn dance. Although it doesn't fit into traditional lineages or definitions of Western Swing, interwar barn dances anticipated, in their own way, the later music of the Honk Tonks.

These two forerunners to the Western Swing scene poignantly capture the kind of musical city Austin was in the 1930s. Western Swing's blending of the Southern string band tradition with the sounds of modern pop and jazz was a musical embodiment of Texas, a largely rural state undergoing early oil industrialization and urbanization. While deeply joined to that overall process and change, Austin's path was different. An aspiring Athens on the Colorado, its popular culture reflected the taste of its adopted youth, the university sets drawn from the state's elite. Consequently, the dominant Hillbilly-modern fusion in Austin during the 1930s was something quite different than the one developing in Dallas or Houston. The competing styles were rooted in class. Two versions of “Western Swing” appeared in the capital during the Depression, each representing a different segment of the college town’s population. The first, similar to the new Country music happening throughout the state, found its audiences in Austin's modest white working classes. The second, which leaned towards the more polished dance orchestra, suited middle and upper class university dancers. While initially the more prominent version in Austin, the second's success was short-lived and, ultimately, a musical dead end.

At the end of the decade, the working class version of Western Swing took on a political edge. W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, who had sponsored one of the pioneering Western Swing bands in Dallas, became governor in 1939. * Through their campaigning and subsequent residency, O’Daniel and his Hillbilly Boys gave Country music a spectacular new public prominence in the state capital.

Predecessor 1: Western Swing in Austin in the 1930s

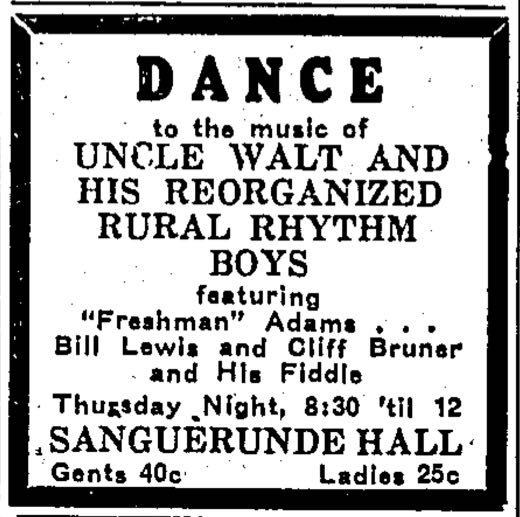

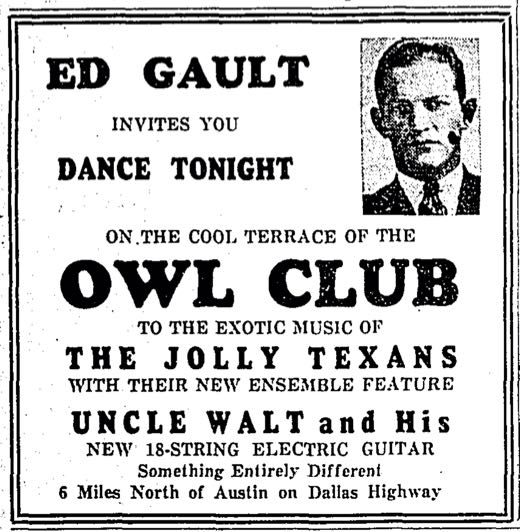

Milton Brown and his band first took notice of Bruner when he was in Austin. According to the fiddler, he had tried to lead a band in the capital during the early 1930s, but went broke, possibly due to the city's early lack of enthusiasm for Hillbilly bands. After playing in Amarillo and San Antonio, he returned to Austin and joined Uncle Walt during the summer of 1935. In 1991, Bruner recalled that

After joining the Musical Brownies, Bruner recorded 49 iconic sides before Brown died in a car crash in April 1936.

There were other Hillbilly groups and string bands in the area at the time, like the “Radio Ranglers,” but it is hard to discern what kind of music many of them performed. One member of Uncle Walt’s band had been performing Old Time music in Austin since the mid-1920s: the bassist and fiddler Steve Lightsey . Lightsey was an important musician in the transition of 19th century fiddle music to 20th century Hillbilly music in Austin. In the mid- to late-1920s, he led an “Old Time String Orchestra” and “Old Time Fiddlin’ Orchestra.” His musicians formed a broad, if still fairly traditional, string ensemble, using bass, violins, guitar, and mandolin. They may have had a wide repertoire, since they appeared both for square dances at car dealerships and at a Mexican Independence celebration.3 Lightsey participated in a number of fiddle contests before the Depression, but, by the mid-1930s, had progressed into Western Swing territory. In 1935, he began playing bass with Uncle Walt and, a year later, he started his own “Rural Rhythm” band (or took over Neal's), which lasted at least until 1938.

After 1941, Lightsey was a frequent performer in Austin’s growing Western Swing club scene. Appearing at The Windmill , The Barn , Dessau Hall , and others, he put together a number of different ensembles: “Steve Lightsey and His Boys,” the “Lone Star Five ,” and the “Rhythm Kings .” The Rhythm Kings were Lightsey’s longest running band and they became a staple group, appearing many times a week between 1946 and 1948. After this period, Lightsey performed with other Western bands, but increasing played in revivalist Square dancing groups, including Henry Hudson's band and Jim Tidwell’s Cripple Creek Ranch Hands.

Predecessor 2: Austin’s Other “Western Swing”

When scholars and writers attempt to historically define what Western Swing is, they typically point to the fusion of older vernacular string band music with contemporary pop music in North Texas in the 1930s.4 In this narrative, Milton Brown and Bob Will’s bands took the older fiddle band, which had been around Texas and the South since the second half of the 19th century, and modernized it. Electricity was one key part: they added the steel guitar, giving it a radically new sound. But they also absorbed elements of radio pop music, adopting the crooning vocals of Bing Crosby and the song structure of Tin Pan Alley.

There was another parallel, if unrecognized, blend of modern dance and hillbilly music happening in Central Texas, however: Barn Dances. “Barn Dances” go back to at least the early twentieth century and were typically associated with revivalist square dance events, fiddle music, and “hayseed” vaudeville comedy acts. In the 1920s, they became prominent as a radio format, providing a “Hillbilly”-style variety program on the air. Texas can reasonably claim to have invented the broadcast genre: the first probably appeared on WBAP in Fort Worth in 1923, led by the fiddler and ex-Confederate soldier, M. J. Bonner. After being copied by the National Barn Dance in Chicago and the WSM Barn Dance in Nashville (which became the Grand Ole Opry in 1927), it became a widespread part of the American radio landscape.

By the 1930s, live barn dances had been around for decades in Austin, appearing at least as early as the first decade of the twentieth century. The events were full of pastoral fantasy and almost invariably decorated with “rustic” props: hay bales, pitchforks, buggies, chickens, cornstalks, old fashioned lanterns, and the like. To compliment the setting, dancers wore “rural” costumes. Men came in overalls and women put on gingham aprons, masquerading as happy farmers and 19th century homesteaders.

The costumes came from a long line of “country bumpkin” acts in vaudeville, where comedians dressed as rubes and acted as uneducated Southern hillbillies. Although they should not be equivocated, the rube was the white analogue of the blackface minstrel in American entertainment.5 Rube—and minstrel—actswere also long standing parts of radio barn dances, including the Grand Ole Opry, well into the 1950s.

Far from purist folk events, the old fashioned and the modern mixed at Barn Dances in interwar Austin. At Steve Lightsey's Barn and Square Dances at the Barker Motor Company—Henry Ford was one of the most well-known and influential promoters of the Barn Dance in the 1920s—his “Old-Time String Orchestra” played “the old time and the new time dances for the young and the old,” giving dancers both “the old Andrews Tunes” and “an occasional popular song.”6

Lightsey’s groups were based in older fiddle music, playing lots of reels and schottische, but also appear to have adapted some modern dance music, including the Charleston. This made them notable, if unrecognized, predecessors to the Light Crust Doughboys and the Musical Brownies. Most of the performers of “old time” music at public dances in Austin were not string or fiddle bands, however; they were dance and jazz orchestras. At UT, the American Legion, and St. Edwards University, brass and woodwind dance bands typically played barn dances. In 1923, for example, Steve Gardner’s orchestra —one of the most popular dance band in Austin at the time—“played a number of barn dance numbers as well as the latest popular music” in the Women’s Gym on campus.7

At the beginning of the next decade, Gardner’s band was still playing a similar mix of old and new, although he sometimes integrated it into a wider variety act. As the Austin American reported, at a Ben Hur Shrine Barn dance in 1931, “Steve Gardner’s orchestra [played] old-fashioned and new fashioned music to suit the dancers taste, and special rube vaudeville acts [were] given by Harley Sadler entertainers and local talent.”8 Similarly, Clarence Nemir’s Orchestra performed “some fine old mountain music, along with newer dance tunes” at Dessau Hall three years later.9 In defiance of later views about the racial identity of country music, white groups were not the only ones who played barn dances. There is also evidence that black territory orchestras, like Sammy Holmes’s Syncopators, were also hired to performed Hillbilly music at white barn dances in the 1930s.10

Apparently, university students thought barn dances were so striking and unique that they would impress European royalty. In April 1936, Prince Paul Metternich of Johannesburg, Germany and Count Aga Dubsky of Vienna visited Austin on their way to the wedding of a Baron and Baronness in Corpus Christi. In response to the aristocrats’ admiration of the University (they said “they would like to go to school here”), the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity made them honored guests at their barn dance.11

Barn dances had become such a hot item at UT by 1937 that the university started to host its own in Gregory Gym , creating a parallel “old time” event to its dance and Swing-centered “All University Dances.” For the first “unorthodox” university barn dance, Weaver’s band “dressed as lads from the hill country and [had] several farm novelties in readiness for the dance.” Gregory gym was “transformed into a typical Texas barn, with harnesses and horse collars adorning the walls and bales of hay to take the place of seats.” But that wasn’t all. They also carted in surreys, buggies, and a cow to help make the sports arena feel especially “rural.”12 These “University Barn Dances” continued for at least the next three years.

Thus, by the early 1930s, when Wills and Brown were inventing their blend of Old Time fiddle and Tin Pan Alley pop music, another version of “Western Swing” had already been present in Austin for a decade. University barn dances also tried to create a hillbilly-modern hybrid, but their starting point opposed the Light Crust Dough Boys, the Musical Brownies, and the Texas Playboys. They featured jazz orchestras playing “hillbilly” music for elite university audiences, not string bands adapting syncopated crooner music for working class enthusiasts.

Context: The Hillbilly Boys and Politics in Austin, 1938-1942

In addition to the increasing fame of Bob Wills and the wide spread popularity of the radio barn dances, a crucial source for Hillbilly music in Austin came from state politics. Indeed, since big bands dominated the capital’s public live music scene, it is very possible that most Austinites’ first experience hearing a Hillbilly or Country band in person was at a Depression-era political rally or speech.

The main catalyst for political Country music was Pappy O’Daniel’s candidacy for Texas governor in 1938. By this point, the attention-seeking candidate already had a deep connection to Hillbilly Music and Western Swing. O’Daniel had been the manager/president of the Burrus Mills flour company, which hired the Doughboys to play an advertising spot on the radio in Fort Worth in the early 1930s. Pappy, who had a flare and knack for self-promotion, joined the band on the program and, through his folklsy persona, became one of the most well-known media personalities in the state. He soon realized the populist political potential for his act and, employing the same character in his campaign as on his show, he launched his pursuit of public office.

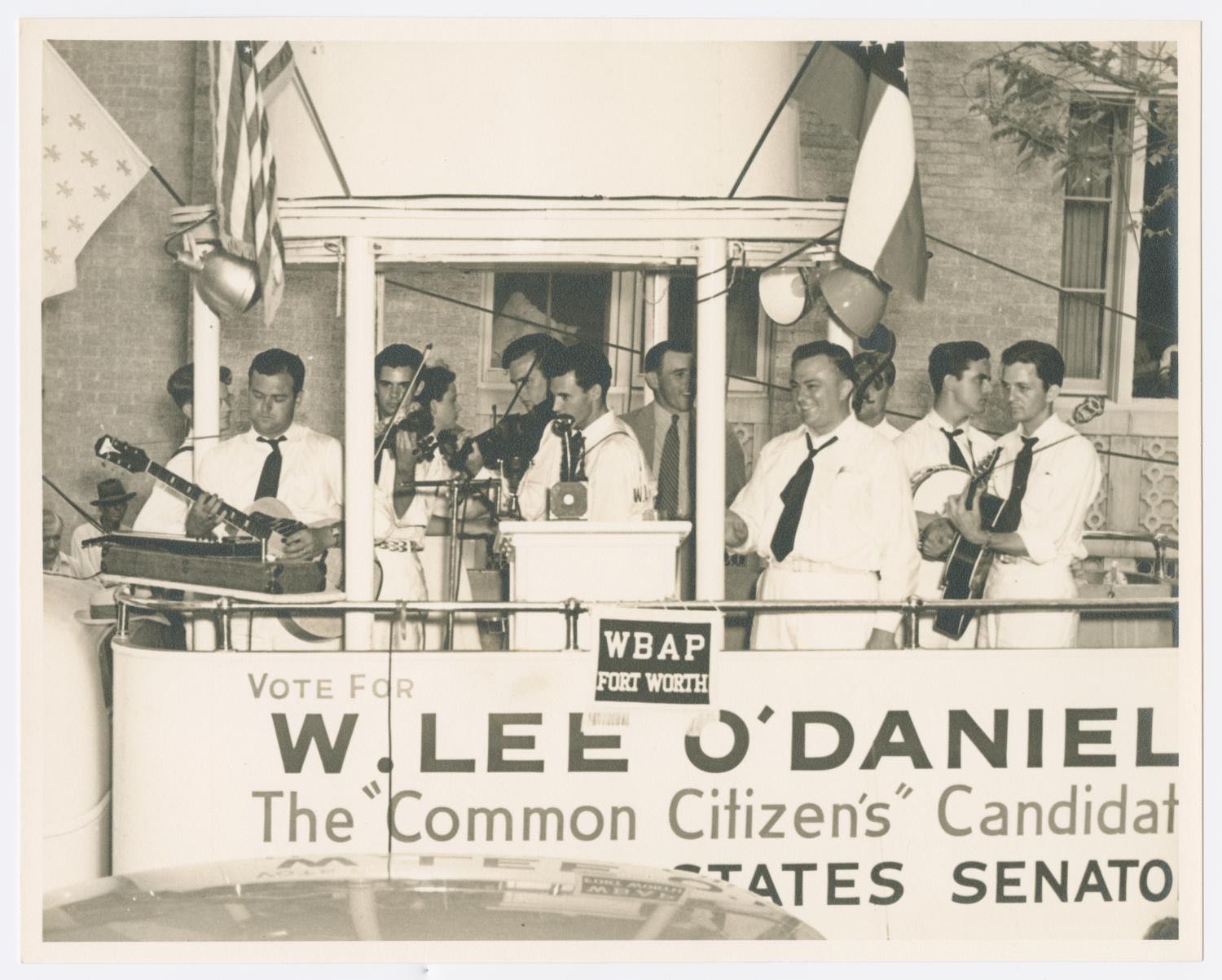

Pappy O’Daniel and the Hillbilly Boys campaigning, 1940s.

[Band at Campaign Stop], photograph, 194X; accessed December 17, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting McAllen Public Library.

The Hillbilly Boys played at every campaign event, welding their Western Swing and Country gospel closely to O'Daniel's populist political message. A contemporary article in the Washington Post describes O'Daniel's strategy and appeal to Depression-era Texans:

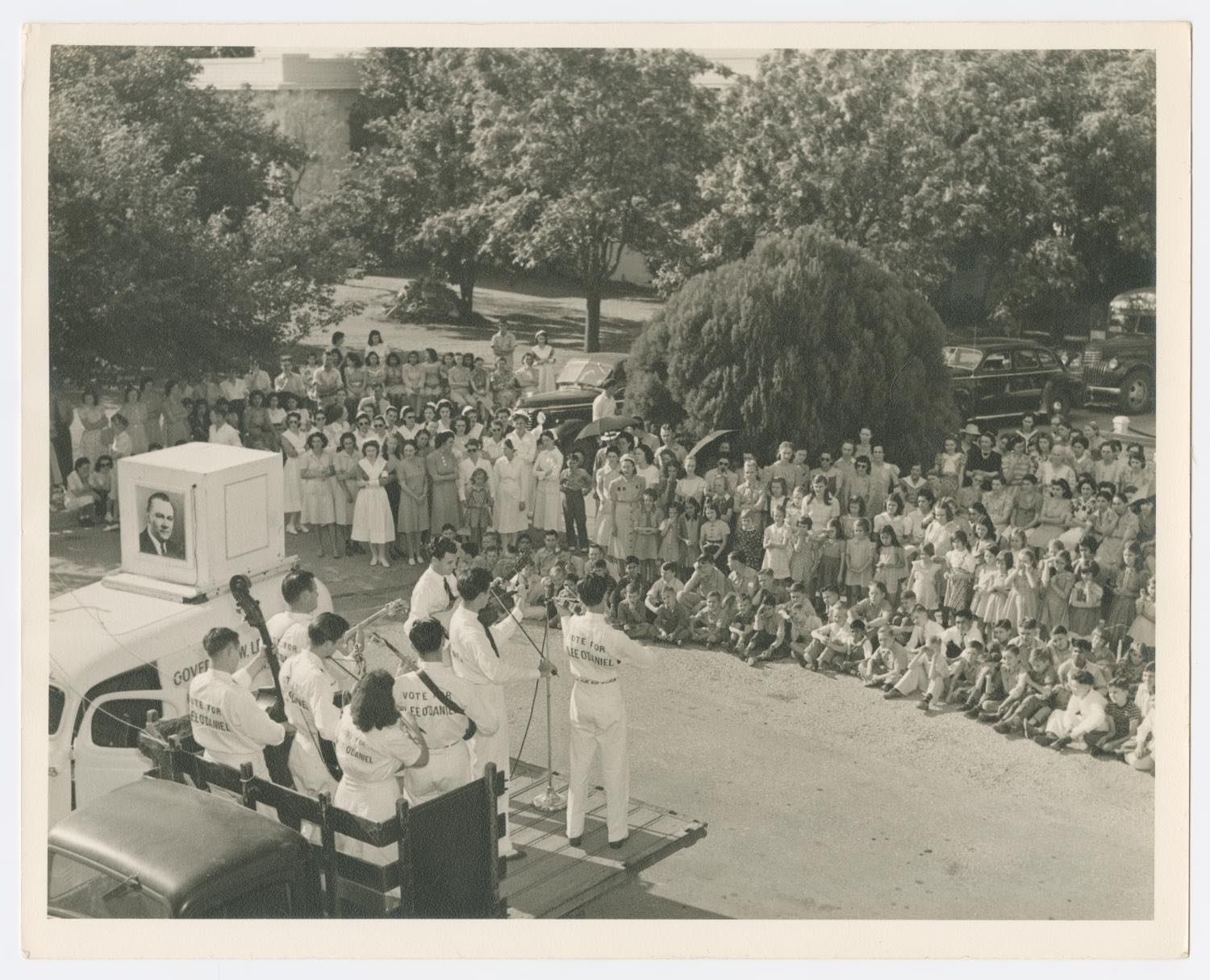

Pappy O’Daniel and the Hillbilly Boys at a campaign rally, 1940s.

[Campaign Rally for W. Lee O'Daniel], photograph, 194X; accessed December 17, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting McAllen Public Library.

The Hillbilly Boy's most spectacular performance was certainly O’Daniel’s inauguration, which drew more than 50,000 people to the University of Texas’s football stadium in January 1939. With such a huge audience in rapt attention, the new governor did not stray far from his regular act. At the end of his speech, he signaled the “Hillbilly Boys,” which included his two sons and singer Leon Huff, to play the hymn “Old Rugged Cross.” Raising the showmanship to an even higher level, O’Daniel then orchestrated the enormous crowd in a sing-along to “Beautiful Texas,” his campaign theme.16

Spectators at O’Daniel’s Inauguration, 1939.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries. “Henry Liesmann of Austin and J.T. Eads McKinny of Fort Worth (with glasses) watch inauguration of W. Lee O'Daniel in Austin, 01/17/1939.” UTA Libraries Digital Gallery. 1939. Accessed December 17, 2020.

This was not the Hillbilly Boys' only performance that day. That evening, the band also played at a six block rally on Congress Avenue between the capitol and the university.17 The following morning, O’Daniel began his first morning as governor broadcasting a “jam session, rural style” from a little room in the Driskill Hotel .18

Shortly after, the Statesman observed the effect of the events on the city. “Fiddle bands achieved a new dignity in the capital’s social life” while, on inauguration day, “‘hillbilly’ was chosen for the name of one cafe and ‘hillbilly biscuits’ were advertised on almost every menu in the city.”19

During the period that the controversial governor was in Austin, from 1939 to 1942, Hillbilly Music was at the center of state government, politics, and local media. After taking office, O’Daniel continued his Sunday radio shows with the Hillbilly Boys. Now broadcast from the governor’s mansion, he used it as a bully pulpit to attack his political opponents and attempt to sway listeners to his policies and opinions. The band tended to play country gospel on these gubernatorial programs, but, on one 1940 broadcast, they supported O’Daniel’s diatribe against his enemies with a modification of the Louis Armstrong tune, “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You”:

The Hillbilly Boys were a constant presence in Austin during these years. They had a daily radio show from the Driskill Hotel and they continued to accompany O’Daniel at all sorts of official and personal events. Members of the band also reaped the benefits of O'Daniel's appointment power, receiving state jobs as barber inspector, a position in the adjutant general’s department at Camp Mabry, and the like. O'Daniel and the Hillbilly Boys' dramatic residence in Austin only lasted three years, however. Defeating Lyndon B. Johnson in a special election, O'Daniel left Texas for Washington D.C. as a U.S. senator in 1941, taking his house band with him.

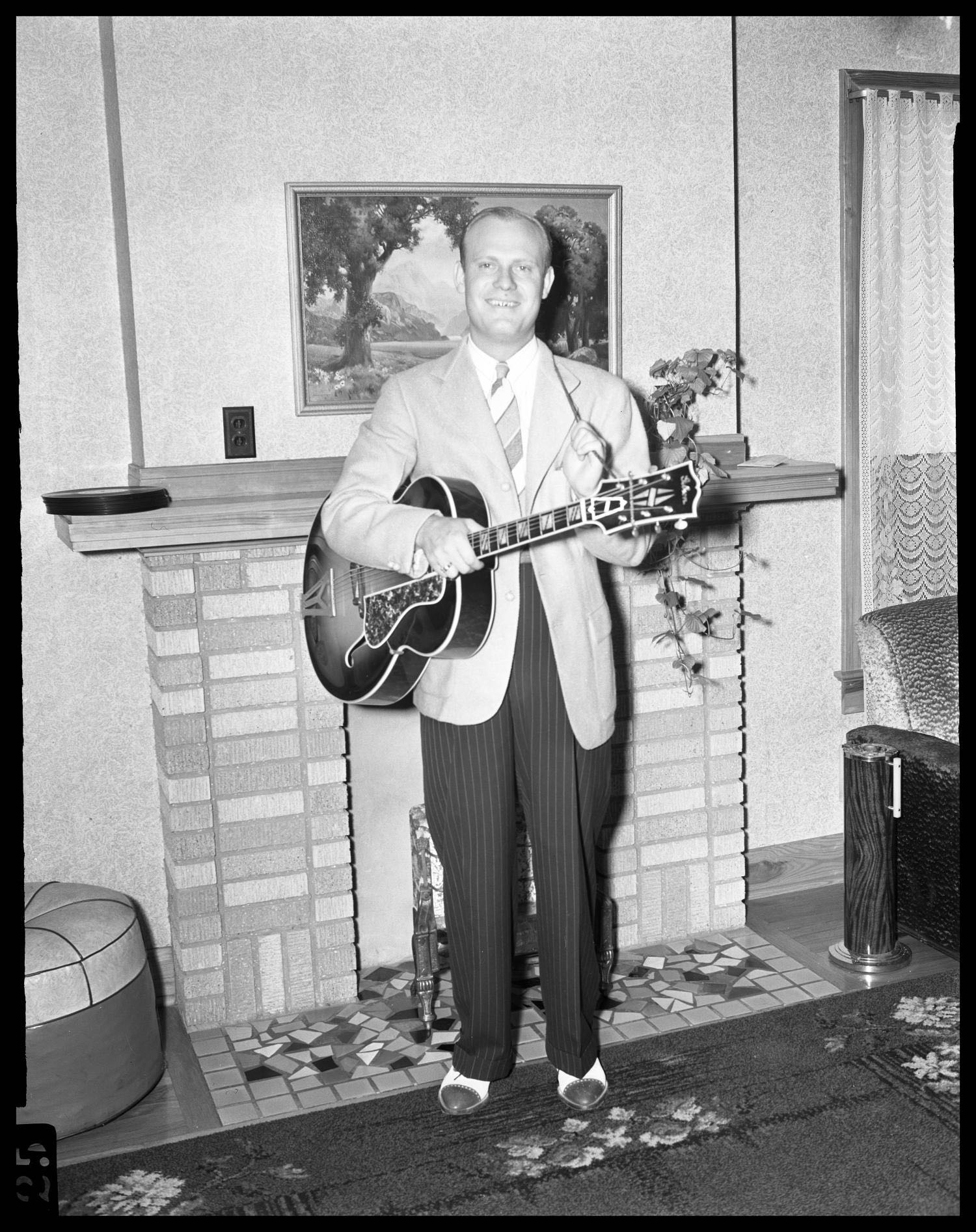

Leon Huff, singer for the Hillbilly Boys, in Austin, 1940.

Douglass, Neal. [Leon Huff Holding Guitar], photograph, May 1, 1940; accessed December 17, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Notes

- Austin American (January 20, 1935). ⏎

- Interview with Cliff Bruner, August 14, 1991, Baylor University Institute for Oral History. ⏎

- Austin Statesman (September 13, 1929). ⏎

- Jean Boyd, The Jazz of the Southwest: An Oral History of Western Swing (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998). ⏎

- Pamela Fox, Natural Acts: Gender, Race, and Rusticity in Country Music (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2009). ⏎

- Austin Statesman (January 15, 1926). ⏎

- Austin Statesman (June 4, 1923). ⏎

- Austin American (October 25, 1931). ⏎

- Austin Statesman (May 22, 1934). ⏎

- Austin American (May 3, 1931); Daily Texan (May 6, 1936). It’s possible that the famous jazz bassist Gene Ramey was in Sammy Holmes’s band when they played their 1931 barn dance. ⏎

- “Nobility Honored with Barn Dance,” Daily Texan (April 22, 1936). ⏎

- “Cow, Politicians at Dance Tonight,” Daily Texan (April 3, 1937). ⏎

- Seth Shepard McKay, W. Lee O’Daniel and Texas Politics, 1938-1942 (Lubbock: Texas Technological Fund, 1944). ⏎

- Floyd Robinson, “O’Daniel Still Talk of the Town,” Austin Statesman (June 29, 1938). ⏎

- Bess Stephenson, “O’Daniel’s Triumph Surprised Nobody in Teas But the Politicians,” The Washington Post (July 31, 1938). ⏎

- Howard C. Marshall, “50,000 Jam UT Stadium as O’Daniel Takes Oath,” Austin Statesman (January 17, 1939). ⏎

- “100,000 Due for Inauguration Rites,” Austin American (January 15, 1939). ⏎

- Lorraine Barnes, “Jam Session, Rural Style, Start Day for O’Daniel,” Austin Statesman (January 17, 1939). ⏎

- “Fiddler Bands Strike Up Tune,” Austin Statesman (January 17, 1939). ⏎

- Gordon K. Shearer, “Odds Even O’Daniel Will Run,” The Austin Statesman (April 1, 1940.) ⏎