The Nash Hernandez Orchestra: An Interview With Ruben Hernandez

Here are three important contexts for the orchestra during the 1940-1960s:

1. The Mexican American Community in East Austin

Following the creation of a new urban plan in 1929, Austin purposefully segregated its black, white, and Mexican American residents. The city used a variety of tools to coerce African Americans and Hispanics into neighborhoods beyond East Avenue (now I-35). By the late 1940s, when Nash Hernandez began organizing his first orchestra, Mexican Americans overwhelming lived in a small enclave in the East, right north of the Colorado river.

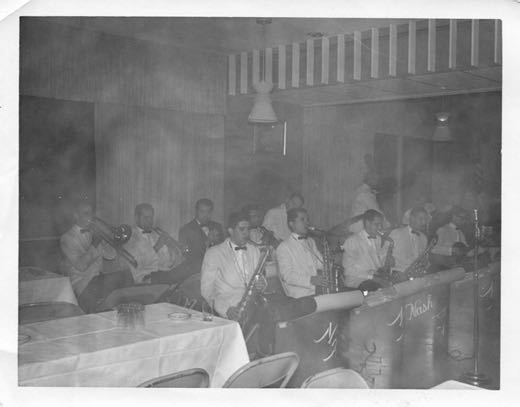

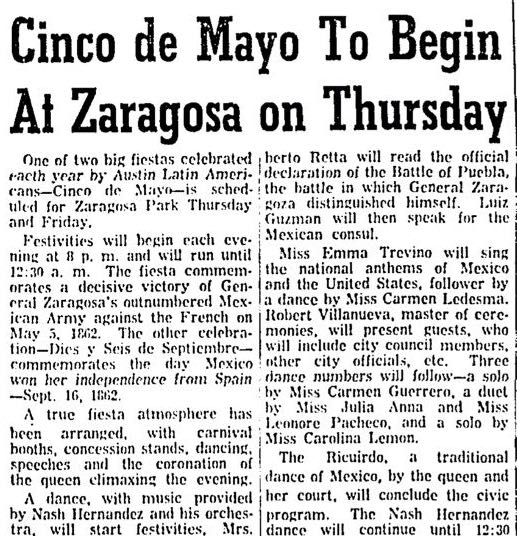

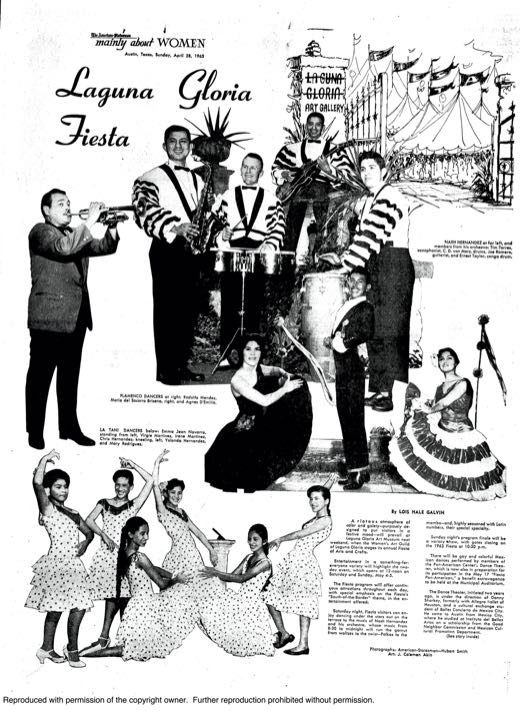

Like the Pan-American Center or Zaragosa Park, the Nash Hernandez orchestra was a binding cultural institution for these mid-century Mexican American neighborhoods in East Austin. It was a community band, a compliment to the early local conjunto groups of Camilo Cantú and Johnny Degollado. Although not the only group of musicians from the area by any means, its frequent performances were deeply intertwined in the lives, identities, and celebrations of its neighbors, giving the orchestra an enduring presence in the area surrounding E. 1st Street (now E. Cesar Chavez Street).

2. The Mexican American Civil Rights Movement

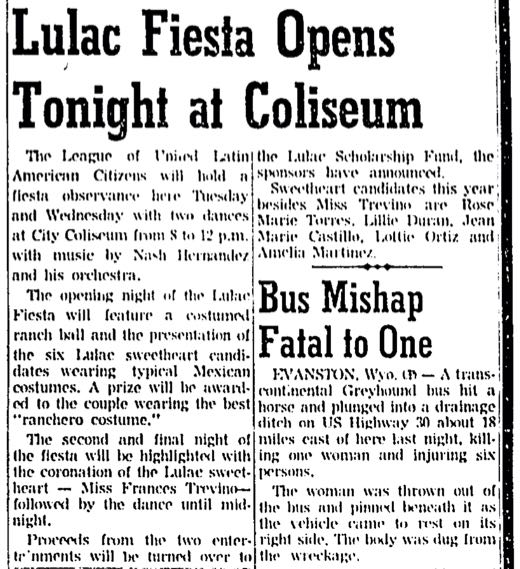

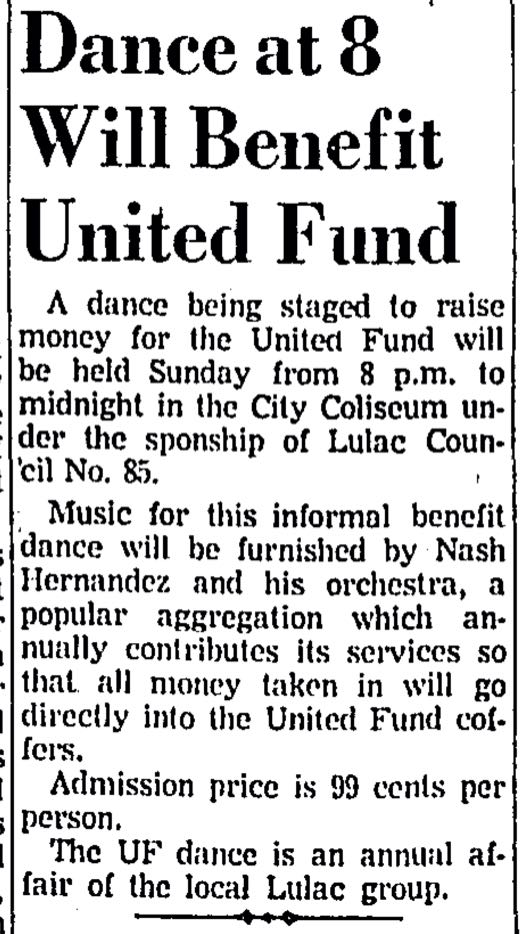

Hernandez’s orchestra had ongoing associations with some of the key postwar Civil Rights organizations in Texas. Although not overtly political himself, as his son Ruben points out, the band was a steady performer for events and benefits for LULAC and the American G.I. Forum. Akin to the NAACP and its role in the Black Freedom Movement, these two activist groups challenged legal and social discrimination against Latinos/as after World War Two.

LULAC (The League of United Latin American Citizens), founded in 1929 in Corpus Christi, was the most prominent civil rights organization to confront the inequalities that existed for Mexican Americans in Texas. Like the NAACP, they used the courts to challenge segregation in public places, including schools, parks, barber shops, and swimming pools. In addition to their legal strategy, LULAC also had a cultural mission: they focused on changing perceptions of Latinos/as. Pushing back on racist characterizations of Hispanics as foreign and alien, they emphasized Hispanic Texans' essential place within American society. They identified Tejanos/as as both “Mexican” and “American.” Mexican Americans, they argued, were a hybrid: they possessed a unique Central American heritage and, at the same time, were part of the U.S.’s mainstream public.2 The American G.I. Forum, founded in Corpus in 1948 by Dr. Hector P. Garcia, focused first on discrimination in military benefits but soon joined LULAC in cases against larger institutions.

The Nash Hernandez orchestra performed for LULAC- and American G.I. Forum-sponsored events during one of the organizations' most active and consequential periods, the decade after World War Two. Hernandez founded the orchestra shortly after one of LULAC’s most significant early legal victories, Delgado vs. Bastrop I.S.D., which ended the segregation of Mexican Americans in schools in Texas. The case was, in fact, local, originating just outside of Austin in the small town of Bastrop. Following this success, LULAC and the G.I. Forum initiated fifteen more lawsuits against school segregation in Texas in 1950. A few years later, in 1954, they won “Hernandez vs. The State of Texas” at the Supreme Court, which forced Texas to accept Mexican Americans on juries. During and after this heady and historic period of civil rights activism, the Nash Hernandez Orchestra was effectively LULAC’s house band in Austin, the center of state politics.

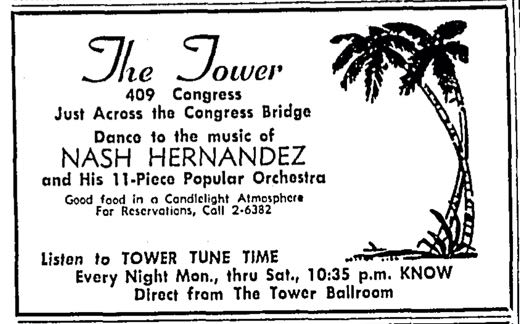

The Nash Hernandez orchestra largely shed their “white” pseudonym, “Jim Nash,” in the aftermath of these powerful legal victories by LULUC and the American G.I. Forum. This refusal to disguise their identity may have been an effect of the successes of the Mexican American Civil Rights movement during this period, a sign of the increasing confidence and public pride in Mexican Americans’ place and status in Texas. Asserting the bands' heritage at mainstream Austin dance venues was a form of cultural work that paralleled LULAC and the American G.I. Forum's activism in the courts.

3. Repertoire: Radio Hits and Latin Music

As a band that played a variety of pop music, from big band swing and rock and roll to rhumbas and Mexican patriotic songs, the Nash Hernandez orchestra was also a musical embodiment of LULAC’s emphasis on the dual identity of Mexican Americans. The group was both an identifiably Latin band and recognizably part of American mainstream music. By playing such a broad repertoire, the orchestra put out those bicultural characteristics in sound, molding it into a wide-ranging horn and percussion driven style. This impulse towards cultural pluralism was, according to the scholar Mario Garcia, deeply characteristic of the generation of Tejanos/as between 1930 and 1960.3

The Nash Hernandez orchestra, on the other hand, played more national- and internationally-oriented Latin styles. In many ways, the band was closer to the transnational bands of Pérez Prado, Xavier Cugat , and Tito Puente, huge hit makers for Latin Music across than U.S., than Villa or Lopez, who played music that stayed localized in Texas and other parts of the Southwest. Instead of a preponderance of orquesta-beloved polkas or waltzes rancheras, they favored the Caribbean-based rhythms of mambo, rumba, merengue, cha-cha, and boleros.4 They also did not use an accordion, the key instrument in the regional sound of orquesta and conjunto music.

Even so, the Nash Hernandez orchestra and the orquestas were two sides of the same musical coin in this period of Texas music. They were all part of a postwar attempt by Mexican American bands in Texas to mix together Latin-identified music with broader popular American styles. In the late 1940s, Villa, the most famous, combined Glenn Miller-like songs with the sound of the accordeon. About a decade later, Lopez adopted rock and roll in his orquesta. At roughly the same time, Hernandez mixed his sets with pop dance band hits, rock and roll, cha-chas, and rhumbas. Thus, the Hernandez band shared a common impulse with the contemporary Villa and Lopez orquestas, even if they did it with a different repertoire and sound.

Notes

- “Varsity Inn Commences Tropical Night,” Austin Statesman, Nov 11, 1960. ⏎

- Cynthia Orozco, No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009). See also Mario Garcia, Mexican Americans: Leadership, Ideology, and Identity, 1930-1960 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989). ⏎

- Garcia, Mexican Americans. ⏎

- This doesn’t mean that the band didn’t also participate in the sound of the orquestas. The Hernandez orchestra’s mid-1950s recording of “La Capital,” for example, is a polka and shares the arranging style and timbre of the Villa orchestra. Orquestas and later conjunto groups also performed caribbean rhythms like the bolero and rumba, even if they still emphasized polkas. For a description of the Nash Hernandez orchestra’s typical Latin genres during its first decades, see “Varsity Inn Commences Tropical Night,” Austin Statesman, Nov 11, 1960. ⏎