Beyond the City Limits: The New Dance Halls

Together, these narratives explain a historic change in sound.

The main sound of Austin’s music scene changed from this in the 1930s,

Henry Busse and his Orchestra, “Begin the Beguine,” Decca 1938

to this in the mid-to-late 1940s,

Melody Masters, “Dessau Waltz,” Lasso 1949

The difference between the two recordings above was more than just an evolution of Texas taste. The transformation from highly arranged big bands to small Western groups also represented a pronounced expansion in where Austinites could see music. One of the most important events in Austin’s early music history was the explosion of dance halls and bars just beyond the city limits. In the decade surrounding the Second World War, tumbledown Honky Tonks challenged college ballrooms and chic night clubs’ near monopoly over the city’s live music scene. And, as the venues altered, so did the music.

(UT Campus)

(UT Campus)

of Women’s Clubs

(Opened 1936)

(Opened 1936)

(Opened 1936)

(Opened 1936)

(Opened 1937)

(Opened 1938)

(Opened 1938)

By 1950, this map was quite different.

(Established 1880s)

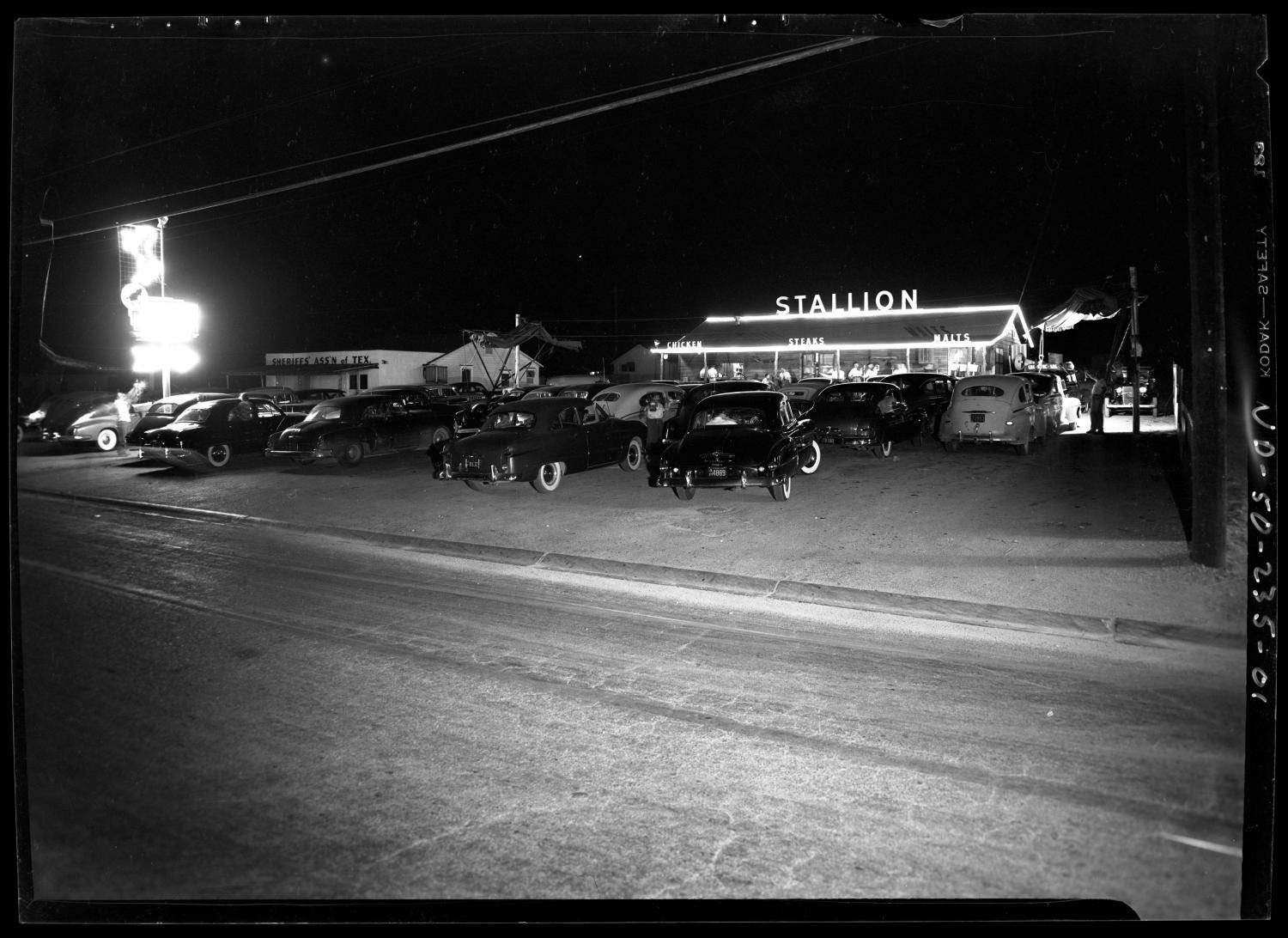

A few of these venues modeled themselves on the night clubs of the 1930s, showcasing dance orchestras and a dinner menu. Some, like the Skyline , started with big bands, but quickly shifted to Country music. From what the sources indicate, however, the vast majority were Honky Tonks and, as they were also known at the time, skull orchards.1

Honky Tonks radically changed the atmosphere and environment of dances in Austin. College events were in self-consciously sophisticated ballrooms or on the polished wood of Gregory Gym. The night clubs of the 1930s advertised their steaks, Mexican food, “modernistic furniture,” and elaborate floor shows. In stark contrast, most forties bands played in quickly built, spartan buildings which booked music to attract customers to buy alcohol.

A party at the Avalon Club, 1948.

Mears, Dewey G. [Jazz Band Playing at Law School Party], photograph, April 30, 1948; accessed December 19, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Cactus Pryor, one of the legendary radio personalities of Texas, emphasized that Honky Tonks and their music were core parts of Austin culture in the 1940s and 1950s. In his book of short memoirs, Inside Texas, he fondly recalled the look and feel of a regular weekday night at one of these area dance halls:

But the Honky Tonks were not just community centers. Johnny Bush, who got his start playing Central Texas Honky Tonks in the early 1950s, described another side of these places vividly:

Not only did they have a reputation as places where women and men picked each other up for pre-marital or extra-marital sex, the Cinderella Club or The Windmill could, in fact, be violent.

Again, Bush paints the scene well:

Pryor’s memory agreed:

The Austin American and Austin Statesman documented some of the more extreme local brawls and attacks.

In a recent interview with the author, steel guitarist Wayne Wood said that brawls were ”commonplace” at Honky Tonks in Austin in the early to mid-1950s: ”some of those places I played, you’d see the fights pretty regular.” He recalled a terrifying fight he saw while playing a gig:

When asked what the band was supposed to do when people started swinging, he said, “they usually said ‘keep playing.’”6

If you didn’t get hit over the head with a chair in a brawl, you stood a good chance of losing something from your car while you drank, danced, and flirted. Stolen cars were routinely dumped by the clubs.

Performing on stage provided little protection from thievery. When Elvis Presley played the Skyline Club in 1955, he had to be warned about the constant thievery at Austin’s Honky Tonks. Maida Meredith, the wife of the leader of the Skyline Club’s house band in the 1950s, kindly instructed the then unknown singer to take his hubcaps off or risk leaving without them.7

(1945-1949)

(1945)

(1946-1947)

(1946-1947)

(1946-1954)

(1947)

(1947-1948)

(1948)

(1948-1949)

(1948)

(1949)

(1949-1953)

(1949-1951)

(1951-1956)

(1954)

(1954-1955)

(1954-1955)

(1955-1958)

(1955-1973)

(1956-1972)

(1958-1960)

Like many of the Honky Tonks, black venues had a boom and bust cycle in the decade after 1945. The clubs of East Austin did fantastically well for the first five years after the war. Johnny Holmes recalled that “the good years were between ’45 and ’49...soldiers were asleep on the ground outside and we were all making money.” In 1950, however, the East Austin entertainment market collapsed and the “competition for the ever diminishing dollars on 11th street became fierce.” It became so bad that Holmes, one of the pioneer music club owners on E. 11th Street, left the Victory Grill to work odd jobs outside of Austin.8

White Western bands also appeared in East Austin clubs for black audiences. In an interview with the beloved Austin music critic Margaret Moser, steel guitarist Jimmie Grabowske recalled that Lavada Durst (the famed local DJ Dr. Hepcat) booked his band for a “Western Night” at the Victory Grill during this period:

Women’s Clubs

Honky Tonks and rhythm and blues bars like the Broken Spoke and the Victory Grill are usually considered quintessential, if under-appreciated, parts of Austin’s local music identity. In a city that loves musical memory, they are the surviving remnants of the old old Austin, before it became the famous hippy/psychedelic/roots connoisseur city of the Armadillo World Headquarters, Vulcan Gas Company, and Antone’s.

In a lot of ways, that reputation obscures how radically these non-elite venues of 1940s changed the landscape of this city’s dances, its audiences, and the kind of music Austinites heard when they went out. Popping up in a city dominated by well-educated big bands and college ballrooms, they were really something very new. They catered to working class audiences interested in Country music, Rhythm and Blues, conjunto music, and sometimes modern jazz, genres often considered too rough, crazy, or unsophisticated for the educated circles of the university. Above all, they hired local musicians who did not play big band Sweet or Swing music, creating novel opportunities for a whole new class of local musicians to play professionally. Together, these things helped produced a new, competing world of music in Austin.

Notes

- Johnny Bush, Whisky River (Take My Mind): The True Story of the Texas Honky-Tonk (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 33. ⏎

- Cactus Pryor, Inside Texas (Bryan, TX: Shoal Creek Publishers, 1982), 49. ⏎

- Johnny Bush, Whiskey River, 36-37. ⏎

- Johny Bush, Whisky River, 37-38. ⏎

- Pryor, 49. ⏎

- Interview with Wayne Wood, Austin, Texas, November 2019. ⏎

- Maida Meredith told this story to the author in conversation in 2019. ⏎

- Ronald Powell, “It isn’t Easy Street” Austin American Statesman (July 2, 1978). ⏎

- Margaret Moser, “Hank, Harry, and Jesse James: Steel Player Jimmy Grabowske Saw it All,” Austin Chronicle (October 5, 2007). ⏎