The New Audiences: Demographics in Austin, 1930-1950

Austin's explosion of Honky Tonks and new music during the 1940s was intimately tied to demographic change. Although always trailing the state’s other major urban areas, the capital had a steadily ballooning population. This abiding growth, especially through migration, had a significant impact on Austin's music scene. Who went out for nightly entertainment was crucial to what got played. To understand why so many new music venues and bands appeared in Austin around mid-century, one needs to pay attention to their patrons.

Many of the new patrons came with the war. Despite its undeniable impact, World War Two did not create Austin's demographic shift, however. It intensified a long term process that had been occurring for decades. Twentieth century Austin was marked by continuous and, altogether, incredible growth. Over the course of 100 years, its population expanded by a mind-boggling 2,849 percent.1 Beginning as a small, provincial university and government outpost, it slowly mutated into a sprawling and culturally rich metropolis. Although ebbing and flowing, its expansion was moderate and consistent: Austin effectively became many different cities over time. The wartime turned Austin into a Honky Tonk city.2

Demographic data, mostly culled from national census records, illuminates a number of things about the new Honky Tonks, music bars, and their audiences:3

1. A long term trend in population supplied Honky Tonk audiences.

The period with the most rapid growth occurred just before the Honky Tonks, Western Swing, conjunto, and Rhythm and Blues transformed Central Texas’s music scene. Judging from the census data, the tens years after 1930 saw the city’s widest expansion.4 This decade was no abberation. It was the crest of a deeper wave of growth between 1920 and 1950, when the population consistently increased by more than 50 percent.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Austin began to mature as a regional center for pop music during this growth wave, its first transformative demographic moment. The city’s status for music raised incrementally, not in one full swoop, however. Before the onset of the financial crisis of 1929, it had already become a home base for territory dance bands like Fred Gardner’s Texas Troubadours and Steve Gardner’s Hokum Kings . In the 1930s, Austin became a national destination, drawing in touring Swing and Sweet big bands for campus dances. During World War Two and after, its local scene filled out and diversified, becoming the Central Texas hub for Western Swing and Rhythm and Blues bands. The first two developments were linked to the size and wealth of the university. The third, however, was based in Austin's cumulative population growth during these three decades. By 1946, the city had enough townies to support a dynamic constellation of working class dance halls.

2. Honky Tonkers were probably migrants to Austin, young, and/or originally from the country.

A large percentage of the audiences in the Honky Tonks and bars of the 1940s were likely made up of people not from or new to Austin. More than half of the additions to Travis county between 1930 and 1940 were migrants (i.e. not children born in the city during the decade) and most of them were young to middle-aged. The number of people arriving in Travis county during the 1940s was even greater: almost 20,000 new people came during the decade and, of these, at least 17,356 were between 20 and 54. In both 1940 and 1950, around 26% of this age range had come to Austin since the last census. In 1950, close to half of this group (43.6%) had moved to the city sometime since 1930. Overall, music audiences were probably fairly young. About 40% of all Austin residents in both 1940 and 1950 were between 15 and 34 years old.5

Austin’s black population grew as well, although not nearly at the rate of its white population. The census records do not allow us to discern exactly how the size of the urban African American community changed between 1930 and 1940, although we can see that Travis county’s black population grew from 15,832 to 19,551 (23%) during this period. By 1940, the vast majority of African Americans in Travis County, 76%, lived in town; only a fraction lived out in the country. It’s much more difficult to distinguish the size of the Mexican American population, unfortunately, since they are included in and not distinguished from the general “white” population in these censuses.

All of this movement occurred in the midst of the “Southern Diaspora,” two massive migrations out of the South between 1900 and 1980, one black and one white. By midcentury, there were about 7.5 million Southerners living outside of the region, mostly in major cities in the West, Midwest, and Northeast.6 It is notable that Austin’s African American and white populations both continuously grew during this period, as residents across Texas and other parts of the South increasingly left to escape racial violence and discrimination; to find jobs in wartime industries; or both.

Black and white residents from Austin and Travis County certainly moved as part of these migrations, but enough new people came to the city to offset these flights. Not all movement led to cities in other states, at least not initially. There was an internal migration in the South that paralleled those to the North and West: farmers and rural residents also left the country for Southern cities, fleeing the collapsing tenant farming business for (hopefully) new lines of work in nearby urban areas. It’s quite likely that large numbers of the listeners and dancers in the wartime Honky Tonks were rural-to-urban migrants, former farmers, or the children of farmers.

Two of Austin’s most influential musicians, Kenny Dorham and Pee Wee Crayton, represented both of these migrations. Dorham, who replaced Miles Davis in Charlie Parker’s epochal bebop band in the late 1940s, was born in Fairfield and moved to Austin during the 1930s. He left for Wiley college outside of Dallas in his teens and, ultimately, relocated to New York City, where he made a lasting musical mark. Crayton, who helped define the West Coast postwar rhythm and blues sound, came to Austin from Rockdale as a child. After growing up and learning music in East Austin, he moved to Los Angeles in 1935 at the age of 21.

3. Audiences and musicians in the 1930s and 1940s had exposure to a wider variety of pop music than before.

The expansion of radio audiences may provide another piece of the puzzle of why Austin's music scene changed during the 1940s. Only a fraction of the city had a radio in 1930—just 21.9% of families (and only 7.3% in the rural areas around the city). Although the major Country music variety shows had been on the air since the early- to mid-1920s, most capital city residents had not heard them at home. This had completely changed by the beginning of the next decade. In 1940, 77.2% of all households in Austin reported a radio (71.9% in Travis County claimed one).

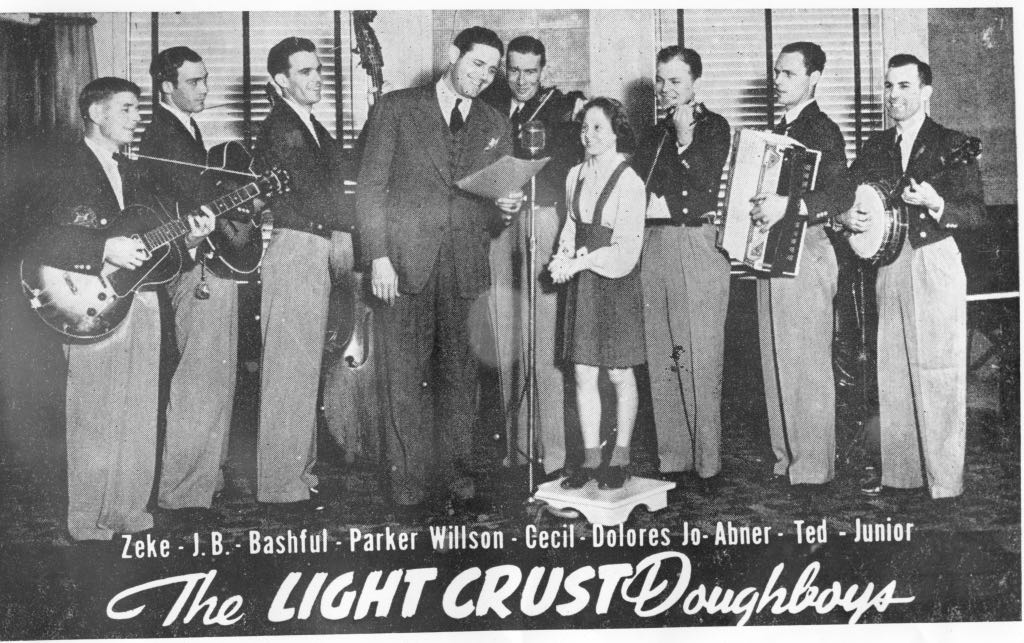

The Light Crust Doughboys, one of the most popular Hillbilly bands of the period, broadcast regularly across Texas and the Southwest in the 1930s and 1940s.

Light Crust Doughboys, photograph, Date Unknown; accessed December 7, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Tarrant County College NE, Heritage Room.

This rise in radio was a crucial source of music for working class audiences, since Country and Hillbilly music did not feature prominently in public concerts during 1930s. As Austinites increasingly brought wireless receivers home during the lean years of the Depression, the city's residents had wider and wider access to the sounds of the Country music from not just other music scenes in Texas, but from across the United States. Consequently, Grand Ole Opry and National Barn Dance broadcasts during the 1930s may have primed the pump for commercial Hillbilly and Country music performance in Austin during the 1940s.

The same may have been true for R&B, gospel quartets, electric blues, orquesta, and conjunto music, although this happened a bit later. During the late 1940s, white-owned radio stations in Austin (and across the United States) finally began to pay attention to the unique desires and tastes of its black and Mexican American residents. Jake Pickle and John Connolly, who would both later become powerhouses in Texas politics, started KVET in 1946 and introduced “Noche de Fiesta,” “Gospel Train,” and “Rosewood Ramble” in 1947 and 1948. Hosted by Lalo Campos, Elmer Akins, and Lavada Durst (a.k.a. Dr. Hepcat) respectively, they featured a diversity of music and DJ speech not previously heard on Austin airwaves: Spanish language and Mexican music, gospel quartets, rhythm and blues, and jive talk.

4. Audiences in the 1940s had a surge of extra cash.

Money was also clearly a factor. More than a third of this period (1920-1950) was taken up by the Great Depression, when most Austinites did not have disposable income to spare on entertainment. It was only when the dire economic circumstances abated at the beginning of the 1940s that Austin’s recent residents could support a deep pool of Country bands and nights out in the Honky Tonks and bars.

If population growth peaked in Austin between 1920 and 1950, income moved in a wave.

IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 14.0

[Database]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 2019.

http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V14.0

During the Depression, wages in Austin dropped and unemployment grew. The records for income during these years, unfortunately, are not nearly as extensive as one would like. It is still possible to get a sense of the general contours from the manufacturing sector, the only group with consistently recorded wages between 1920 and 1940 in Austin. After rising the decade before, manufacturing workers’ income fell more than 16% between 1930 and 1939. Not surprisingly, unemployment rose as well. Compared to much of the rest of the nation, Austin’s financial environment was less desparate, however. As a city dominated by two big institutions—state government and the university—its reported unemployment was relatively low, just 5.6% when the national average was between 15% and 17.5%.

Ten years later, wages had risen dramatically and unemployment had fallen. Manufacturing workers, the highest paid wage earners in Austin, made an average of $945.84 per year in 1939. In 1950, the median household income was $2126, almost 125% more, while unemployment had dropped to 1.4%.7

Thus, in the 1940s, most regular Austinites had cash to spend for the first time in more than a decade. This mattered a great deal for the Country and Western and R&B-oriented Honky Tonks and bars. As steel guitarist Wayne Wood confirmed in a recent interview, Austin’s Country venues in this period were deeply working class. They were primarily patronized by “working people,” he remembered.8

5. The military played a key role in jump starting Austin’s Honky Tonk and Chittlin’ Circuit Businesses.

Another crucial population fed the Honky Tonk business in the 1940s. Austin’s (relatively) flush residents were supplemented by a huge, sudden growth in regional military personnel. World War Two did not just bring jobs, it also brought bases. Three major installations opened between 1941 and 1942: Bergstrom Army Air Field in Del Valle (1941); Camp Swift, north of Bastrop (1942); and Camp Hood (later “Fort”) near Killeen (1942). These installations joined Camp Mabry, which had been opened in 1892 in Northwest Austin and housed the Texas National Guard. Together, these new bases and camps raised the Central Texas population substantially. At their peaks during the war, Hood trained close to 100,000; Swift held around 50,000; and Bergstrom contained 2,500.9

For these soldiers, Austin was an entertainment capital and swarms of young enlisted men went into town whenever they could. Camp Swift was not stingy with its leave passes and a huge bottleneck of GIs overwhelmed the city's bus stations. Newspapers at the time reported that lines for public transportation were so long that the city and camp discussed setting up a special shuttle train to carry soldiers to and from town. One article in 1942 claimed that “10,000 servicemen swelled Austin’s rapidly growing population over the weekend.” Many of these soldiers found their way to dance halls and ballrooms. That same year, two August articles noted that between 1200 and 2000 people from the bases recently crowded dances at the Driskill Hotel in downtown Austin.10

Camp Swift, 1942-1945.

Aerial view of Camp Swift including Headquarters, Post Finance Office, U. S. Post Office and north cantonment area], photograph, 1942/1945; accessed December 7, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Del Valle (Bergstrom) Air Base, 1943.

Douglass, Neal. Del Valle Air Base Hangar, photograph, January 6, 1943; accessed December 7, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

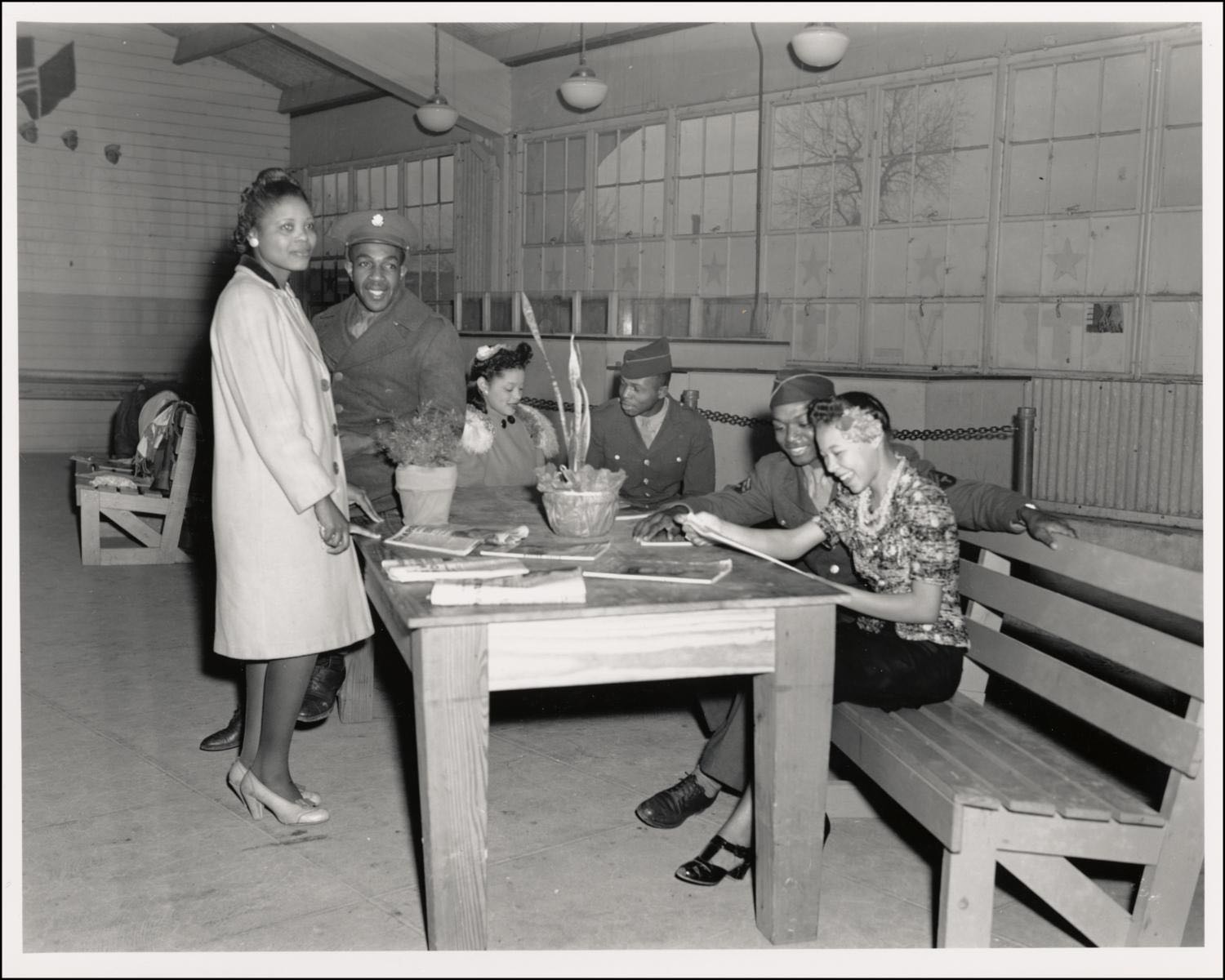

African American soldiers were also stationed at these bases and, being located in a Jim Crow state, they could only visit restaurants, bars, and stores in East Austin. In 1944, the Statesman quoted an unnamed source from Camp Swift that around 10,000 African American soldiers typically also came into Austin on weekends. As Johnny Holmes, owner of the postwar Victory Grill, later pointed out, soldiers created a short-term boom for East Austin entertainment and music.11

Negro War Recreation Council Building on East Avenue (now I-35), 1944.

[Interior view of the Negro War Recreation Council Building with 3 women and 3 Soldiers around a table], photograph, January 6, 1944; accessed December 7, 2020, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

White Austin responded to these soldiers’ movement with racist fear. Repeating old stereotypes of licentiousness, the city and press focused considerable attention on their presence’s potential for an outbreak of venereal diseases. One 1943 Austin American article claimed that “Negro Soldiers are especially involved in the increase [in Sexually Transmitted Diseases] here.” Dr. J.M. Coleman, director of the city’s public health and welfare, complained that that “the problem is one particularly involving the negro soldiers visiting Austin. The rate for these men is about 20 times that of white soldiers.”

In 1944, a Travis County grand jury issued a report stating that Camp Swift authorities had leveled the accusation in the opposition direction: soldiers had caught STIs in Austin, not the other way around. Camp authorities alleged that Austin had the highest VD rate “in the eighth service command” (Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma).12 Although the rates of VDs among all GIs were at issue, the city honed in on black soldiers and East Austin. After the report became public, Mayor Tom Miller

6. The war radically changed UT’s student population and began to shift student taste.

The war also deeply affected the University of Texas. In 1941, wartime gasoline rationing forced the university to temporarily cancel it premier music performances, the All University Dances. Since major touring bands could no longer reach Austin, students began to flock to the city’s night clubs for entertainment. Soon, rationing made even trips to the outskirts of town more difficult and the campus opened up its own venue, the Longhorn Room.14

At first, the draft drained the college of its male students and prompted a significant drop in registration. By 1943, there were fewer men than women for the first time since the late teens. This was unusual; there was typically a stark gender imbalance at UT. Before the war, twice as many men attended the university as women.

After the fighting’s end, UT’s rosters soared. Veterans, equipted with G.I. Bill support, came to the university in droves. The following academic year, 1946/1947, broke all records and remained the decade's peak: 19,271 students enrolled, more than half of which—10,809—were veterans. Before the war, UT's largest student body had been 11,078 (1940). At one of its wartime lows, in Spring 1943, there were exactly 7,000 students at the university, 36% of the postwar high.15

In stark contrast, Texas’s underfunded African American schools could not accomodate their burst of applicants during these years. Around 3900 black students could not find a place in the Lone Star state’s segregated higher education system in Fall 1947. Samuel Huston and Tillotson Colleges in Austin had just 996 spots in all, a tiny number compared to its large, white, and well-funded colleague. That same year, the only state-funded black college, Prairie View, had to turn away almost half of its applicants (1433 out of 2943 were rejected because of lack of space). UT only turned away one applicant while enrolling more than 17,000. The single applicant it rejected was black.16

Overall, this expansion of the student population was significant, since students had typically composed the bulk of music audiences in Austin. Now there were twice as many students. Moreover, since the G.I. Bill provided funding to people who would have never been able to go to college otherwise, the college ranks were considerable more socio-economically diverse. This was incredibly important for Austin's growing cascade of Honky Tonks, for, as noted above, dancers at the Country music dance halls were primarily working class. 1946/1947, the year UT had its record enrollment, was the same year the Honky Tonk scene really took off and expanded.

Notes

- For comparison, New York City grew around 133% from 1900 to 2000. ⏎

- Although now almost exclusively associated with Country Music, Honky Tonk is used here in a wider sense to include working-class African American and Mexican American music bars and clubs as well. For the term’s early association with African American venues and jooks, see Katrina Hazzard-Gordon, Jookin’: The Rise of Social Dance Formations in African-American Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 76, 86-89. ⏎

- Unless noted otherwise the following text uses data from the following census sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Travis County 1930 Census, Prepared by Social Explorer. (accessed Oct 1 13:00:00 EST 2010); U.S. Census Bureau, Travis County 1940 Census, Prepared by Social Explorer. (accessed Oct 1 13:00:00 EST 2010); U.S. Census Bureau, Travis County 1950 Census, Prepared by Social Explorer. (accessed Oct 3 13:00:00 EST 2010); U.S. Census Bureau, Travis County 1940 Census Tracts, Prepared by Social Explorer. (accessed Oct 4 13:00:00 EST 2010); U.S. Census Bureau, Travis County 1950 Census Tracts, Prepared by Social Explorer. (accessed Oct 5 13:00:00 EST 2010). ⏎

- Since the census typically only gathered data at the beginning of each decade, it is difficult to judge population changes outside of this framework. The period of the largest expansion may have been 1935-1947, for example, but it is not possible to parse this out of the historical data from the census. ⏎

- The net-intercensal age cohorts table technique used here for determining residents who moved to Austin is taken from Bernadette Pruitt’s “For the Advancement of the Race: The Great Migrations to Houston, Texas, 1914-1941,” Journal of Urban History 31(4), 2005 and Earl Lewis, “Expectations, Economic Opportunities, and Life in the Industrial Age: Black Migration to Norfolk, Virginia, 1910-1945,” in The Great Migration in Historical Perspective, Joe William Trotter Jr., ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991). ⏎

- James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005). ⏎

- Most households probably only had a single wage earner in Austin in 1939. The census reported that 18.9% of women were in the labor force and 9.2% of female workers were unemployed. The 1940 U.S. Census employed a definition of employment that more accurately reflected women’s role in the market than the censuses before. Nancy Folbre and Marjorie Abel, “Women’s Work and Women’s Households: Gender Bias in the U.S. Census,” Social Research Vol. 56, No. 3 (Autumn 1989), 547-8. In 1949, 58% of households in Austin made $1500 or more. For real wages, visit U.S. Bureau of Labor’s calculator: https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. ⏎

- Interview with Wayne Wood, November 2019. ⏎

- Bergstrom Army Air Field was originally named Del Valle Army Air Base. Jim Greenwood, “Bastrop County Wonders as Camp Swift Passes Out” Austin America (March 16, 1947); Frederick L. Bruier, “Fort Hood“ in Texas State Historical Association Handbook, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbf25; Virginia Forbes, “Bergstrom Still Big Payroll to City,” Austin Statesman (June 11, 1948). ⏎

- “10,000 Troops Feted Here,” Austin Statesman (November 16, 1942); “USO Entertains 1,200 at Dance,” Austin Statesman (August 24, 1942); “2000 Attend USO Dance,” Austin Statesman (August 03, 1942). Robert Ellis, who was stationed at Swift in 1944, remembered in his World War Two memoir See Naples and Die that “[the] weekend pass policy was liberal, so we were able visit Austin frequently.” Robert Ellis, See Naples and Die: A Ski Trooper’s World War II Memoir (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1996), 83.] Judging from the many reports of fights and arrests involving soldiers in the 1940s, we know they frequented Honky Tonks and music bars. [“13 Soldiers Held in Jail After Brawl,” Austin Statesman (February 5, 1944); “Person Who Tried To Stop Fight Cut,” Austin Statesman (April 12, 1945); William J. Weeg, “Blue Dahlia Club Brawl Pictured by G.I.s in Court,” Austin Statesman (October 22, 1948); “Two Charged: Hit-Run Cases Probed Here,” (May 22, 1950). ⏎

- Ronald Powell, “It isn’t Easy Street” Austin American Statesman (July 2, 1978). See also the recollections of Ernie Mae Miller, as recorded in Margaret Moser, “Bright Lights, Inner City: When Austin’s Eastside music scene was lit up like Broadway,” Austin Chronicle (July 4, 2003). ⏎

- “Austin’s VD Rate Highest,” Austin Statesman (March 1, 1944). ⏎

- Fred D. Thompson, “Mayor, Stirred by Grand Jury Report, Calls Meeting on Venereal Diseases,” The Austin Statesman (March 2, 1944). ⏎

- “A Night Club for the Campus! ‘Longhorn Room’ Opens Friday,” Daily Texan (November 2, 1941); “Round Up Fans to Miss Longhorn Room,” Daily Texan (April 2, 1943). ⏎

- “16,793 Students Enrolled at UT,” The Daily Texan (March 28, 1947); “Long Session Enrollment Hits 10,835 Mark,” The Daily Texan (February 6, 1941); “Enrollment Reaches Exactly 7,000,” The Daily Texan (February 9, 1943). ⏎

- “Crowded Texas Negro Colleges Turn Away 3,900 Applicants,” The Daily Texan (March 28, 1947). ⏎

- Charley Trimble, “Radio Going ’Billy Mad in Austin,” The Daily Texan (August 18, 1950). ⏎

- “‘Eyes of Texas’ Is Serious to Us, Even if Kay Kyser Tries to Play It,” The Daily Texan (November 7, 1942); “UT Fans Shun Serials,” The Daily Texan (February 11, 1947). ⏎

- Herby Herbsleb, “If You Like Variety in Fun, You’ll Like Austin,” The Daily Texan (August 25, 1949); Pat Bomar, “Five Picture Shows Made Austin’s 1913 Nightlife,” The Daily Texan (May 5, 1950); “Hillbilly Music Centex Favorite,” The Daily Texan (February 7, 1947). ⏎

- “Avalon has Night for UT ‘Hillbillys’,” The Daily Texan (October 27, 1948). ⏎