The Forgotten Swing and Rhythm & Blues of Johnny Simmons

On August 9, 1955, the now iconic DJ Dr. Hepcat (Lavada Durst) hosted “Johnny Simmons Night” in Doris Miller Auditorium. A celebration of the achievements of one of Austin’s musical elder statesmen, it gathered many members of Central Texas’s small but rich postwar African American entertainment world under one roof. A tribute from Dr. Hepcat at this time was no small compliment. Hepcat’s local R&B and Swing radio show, “The Rosewood Ramble,” had made him one of the most powerful cultural voices in the East Austin community.

Tragically, “Johnny Simmons Night” was a memorial, a benefit for the musician’s widow after his sudden death in San Antonio the week before. Simmons’s reputation during his lifetime—in the 1940s, a San Antonio newspaper labeled him “one of the state’s favorite bands” and the Austin American described “one of Austin’s best known musical figures” at the time of his death—stands in stark contrast to his current obscurity. He is now an undeservingly forgotten figure, rarely discussed or remembered. When he passed away, Simmons had been perhaps the most popular black bandleader in Austin for almost two decades.

Simmons and Durst were primary figures in the first generation of postwar, post-Swing African American music in Austin. Most memorialization of East Austin’s “stroll,” its main cultural and economic areas during Jim Crow, remembers the 1950s and 1960s electric blues bands and chittlin’ circuit soul acts at the Victory Grill and Charlie’s Playhouse. At least part of this focus likely stems from the later influence of Clifford Antone, who cemented the city’s association with guitar-driven and post-war Chicago blues. Another bond came from the talents of local guitarists like T.D. Bell, W.C. Clark, Blues Boy Hubbard, and Matthew Robinson, who helped bring attention back to the East Austin scene of the 1960s decades later.

At the time of the pianist’s death in 1955, however, Simmons and Durst were linked to jump blues and early rhythm and blues, major stylistic departures in pop music by African American musicians during the early-to-late 1940s. Simmons, in fact, may have led the first jump and/or rhythm and blues band in Central Texas, making him one of the city’s major mid-twentieth century transitional figures. This was not how he came to prominence, however. A musician who had come of age before the war, he had been one of the main purveyors of Swing for local black and white audiences in the late 1930s.

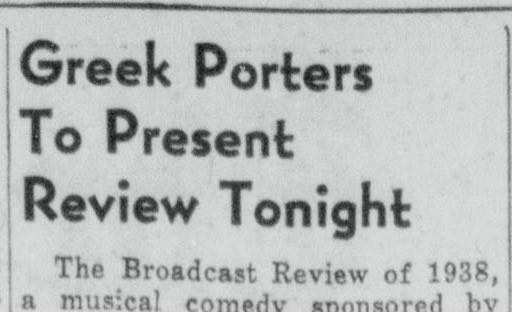

Likely born in 1920, Simmons began leading a Texas territory band at the tail end of their most distinctive period. Territory bands in the Southwest, including Texas, had pioneered a distinctive style of big band music during the late 1920s and 1930s, a regional sound that was soon transformed into a foundation of the broader Swing movement. Simmons was impressively young—just 17 years old—when his band was first documented in 1938. His orchestra, “the Blue Devils,” may have been modeled on Walter Page’s legendary territory band of the same name, a group that had toured extensively through Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas during the pervious decade.8

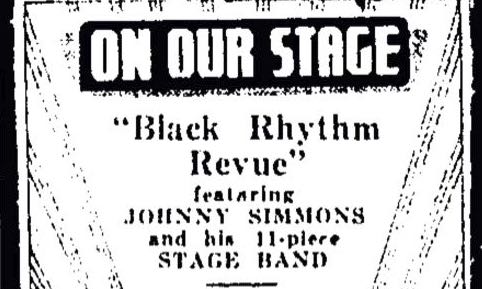

During his earliest performing years, local theaters and concert promoters clearly identified Simmons and his band as part of the national Swing movement, as a 1939 advertisement for his “Black Rhythm Revue” at the Capitol Theater shows. He also performed regularly for white UT fraternity, sorority, and club dances from the late 1930s until the mid-1940s. Simmons, in fact, was one of the only local black bandleaders that UT-affiliated groups would regularly hire. This was financially significant, since college dances were the most lucrative and consistent work for musicians in town during this period. Although documentation of these gigs is sparse, Simmons’s ability to secure these jobs—including solo piano performances—during the height of Jim Crow suggests that he was a skilled navigator of the racial etiquette demanded by white audiences.

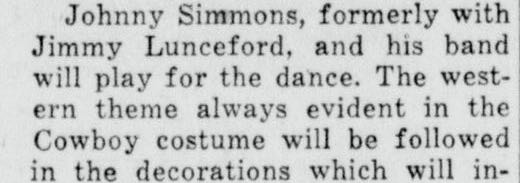

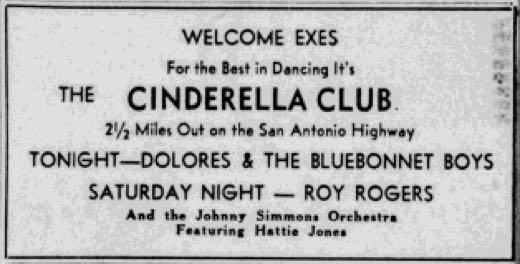

Simmons’s time with Lunceford must have been short, for he was a centerpiece of Austin’s dance culture throughout the 1940s. Simmons fronted groups that held weekly to monthly gigs at many of the city’s major white dinner and dance venues: the Varsity Inn and Jack and Helen’s in 1943; Opal’s and the Trocadero Dinner Club in 1946; Club 81 in 1947; and the Cinderella Club in 1949. Simmons’s performances at UT dances seemed to have dried up after 1946 and, by the end of the decade, his (documented) work in Austin primarily came from these segregated public performances.3 As Austin’s music club scene began to blow up after the end of the Second World War, Simmons was a consistent element of it, often playing in the same places as Honk Tonk Country and Western Swing bands.

Although he may have chosen to not pursue industry fame with Lunceford, Simmons did not remain not purely local. His band had a presence on the black Central Texas dance circuit. Simmons’s orchestra, for example, played for Don Albert’s Famous Door club in San Antonio in the late 1930s and early 1940s, including for some Pepsi-Cola-sponsored “battle” dances for a Southwest championship. The association with Albert probably probably signaled the band’s talent, for the club manager led the most visible big band in Texas at the time. In San Antonio, Simmons’s band also played alongside the sight-impaired singer Al Hibbler a few years before he became Duke Ellington’s vocalist.

As far as can be determined, Simmons’s music transformed with the times and with his employers. He was described as “red hot swing” in 1939 and he seemed to have kept up a dance orchestra throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. The band was versatile and, at least once in 1943, he played a “barn dance” with old time and hillbilly music for a UT fraternity (see the 1946 ad above for another example).

Although no recordings are known to exist, Simmons may have been a member of the Texas Barrelhouse piano tradition like Durst. In a number of ads and articles in the 1940s, he is described as a “boogie woogie” pianist, a distinctive style rooted in the itinerant barrelhouse performers of East Texas from the late 19th century through the 1920s. Austin became fertile ground for this tradition due to the influence of Robert Shaw, a pianist associated with the Santa Fe barrelhouse style who moved to the city in the early 1930s. Similar pianists like Baby Dotson, Black Tank, and Boots Walton played around town in the 1920s as well, Durst recalled7. If this is this case, Simmons represented a unique local melding—and possibly the stylistic continuity—of barrelhouse, Swing, and early jump blues.

Robert Shaw’s musical career was re-invigorated during 1960s, when he found a new audience among young white members of the Folk-Blues revival in Austin. He would remain an elder statesman of the local music scene until his death in 1985. This concert was taped on Shaw’s 75th birthday in 1982.

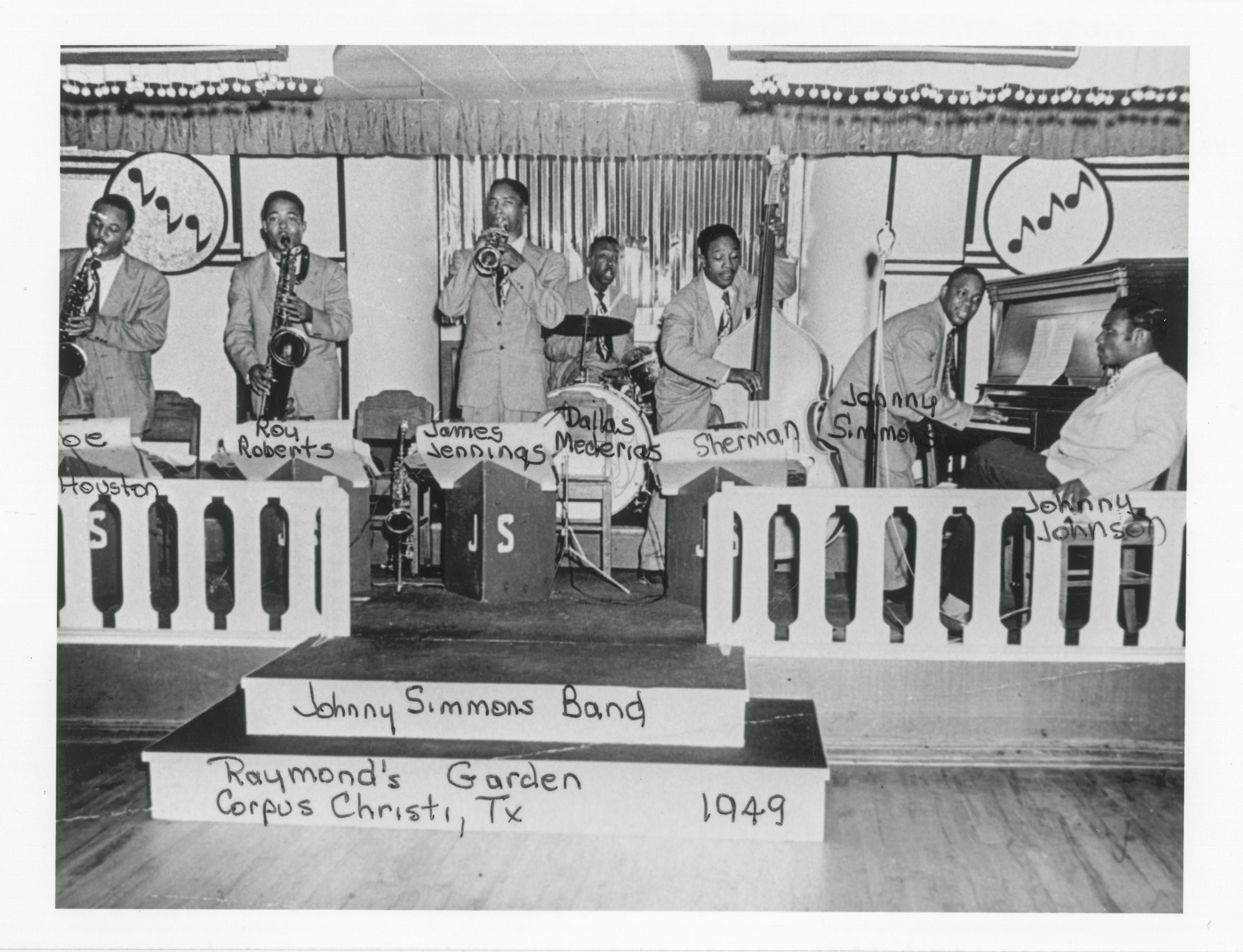

Simmons also featured some of the best African American talent in Central Texas during the period. Two remaining photographs of his late-1940s bands in the Austin History Center collection show the trumpeter Paris Jones and saxophonist Joe Houston. Jones, a cousin of the pioneering jazz bassist Gene Ramey, taught the famous bebop trumpeter Kenny Dorham, who grew up in Austin. Here is how Ramey remembered him in an oral history in the 1970s:

From these indications, Simmons’s bands in the late 1940s may have been a fascinating local mix of Swing, jump blues, and bebop.

Johnny Simmons’s career exemplified what it meant to be a local working musician in Austin between the 1930s and 1950s. Although he possibly had a brief chance at national prominence in the early 1940s with Jimmy Lunceford, he existed almost exclusively within a small regional music world—likely just in Austin, San Antonio, and the small towns around them in Central Texas. He was clearly talented and that accomplishment garnered him well-deserved celebrity in his home territory. Since Austin was so far removed from the major music industry centers, however, his star rose and faded with his lifespan and his locale’s memory.

As a musician making a living in a small town, Simmons was not wedded to a single style, but exemplified a certain professional versatility. It’s hard to say definite things about his music without recordings, but he likely was rooted in—or had absorbed elements of—the Southwest territory bands, Texas’s barrelhouse pianists, and the emerging rhythm and blues of Houston-Gulf Coast. Even with these continuities, he played for different audiences in different decades, from white college fraternities in the 1930s to African American high school students in the late 1940s. And as other African American musicians in Texas during the period have testified, bandleaders were expected to play certain repertoires and styles according to the identity and circumstances of their dancers.4

Simmons also represented Austin’s larger relationship to the music industry. Although it later became famous as a place that went against the commercial grain, the capital was unique in Texas between the 1930s and 1950s for how closely it followed national stylistic trends. Simmons, who played Swing at its height in the 1930s then R&B in the late 1940s as it superceded big band music, embodied this trait. His music seems to have always stayed in touch with the popular music of the moment. The Nash Hernandez orchestra—which the bandleader’s son described as fundamentally a “cover band”—was similar, although it specialized in Latin popular music as well. Ultimately, Simmons and Hernandez were among the bands who best represented what was noteworthy about Austin during the pre-counter-culture period.

Notes

- Daily Texan January 4, 1946. ⏎

- The only likely entry for Simmons in census records (1940) indicates that he did not finish High School, however. If he did join Lunceford, who was famous for hiring college-educated musicians, he must have been a skilled and polished pianist. ⏎

- As seen above, there is photographic evidence that Simmons also played dances during this period at L.C. Anderson, the African American high school. Simmons may have played lots of other local gigs for black Austinites, but the local newspapers did not record them. ⏎

- This was the case in many places in Texas during this period. For example, see Roger Wood, Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), 29-30, and “Interview with Don Albert,” May 27, 1972, Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz, Tulane University. ⏎

- “Interview with Gene Ramey, 1977,” Box 2.325, Gene Ramey Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- Liner Notes to Lavada Durst, “The Piano Blues of Dr. Hepcat,” DocArts, http://www.docarts.com/piano_blues_of_dr_hepcat.html ⏎

- Liner Notes to “The Piano Blues of Dr. Hepcat.” ⏎

- Page’s group, wich included the Texans Buster Smith and Hot Lips Page, was a precursor to Count Basie’s orchestra, one of the gold standards of Swing when Simmons began leading his own bands. ⏎