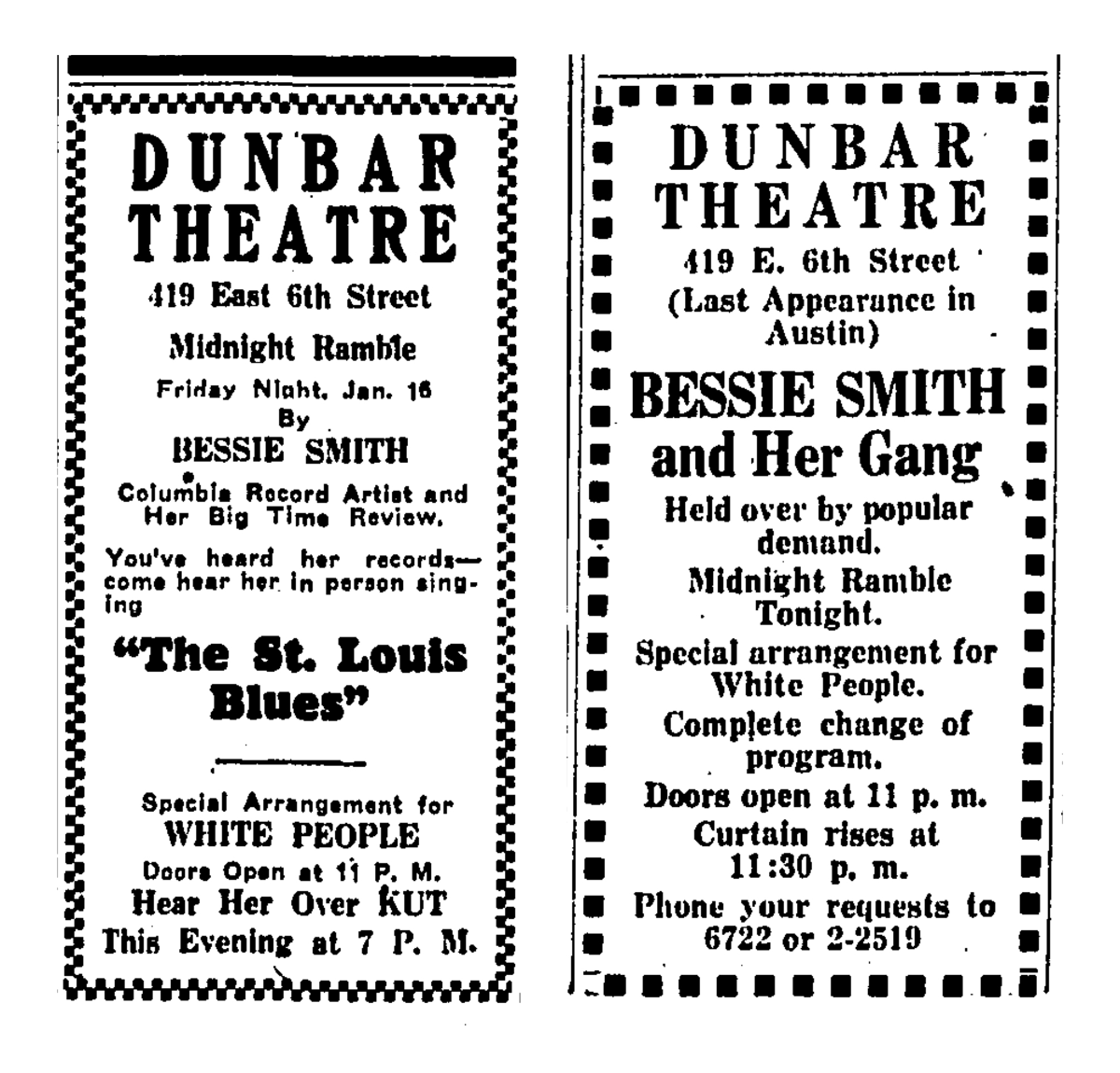

Austin Statesman (January 16, 1931). Austin Statesman (January 20, 1931).

I recently came across the ads above as I sifted through old issues in the Austin American Statesman’s digital archive. Although fairly bare in detail, they are quite noteworthy in at least two respects. First, they are the only known performances in Austin by Bessie Smith, the most famous and historically ascendent of the 1920s “Blues Queens.” Second, they are rare traces of the Dunbar Theatre, one of downtown Austin’s African American movie/vaudeville houses from the interwar period.

By the time she performed in Austin, Bessie Smith had been one of the stars of black vaudeville and the “race” recording industry for more than a decade. Smith, who began as a child street performer in Chattanooga, cut her teeth performing in the early African American entertainment world of the 1910s. By 1920, she was a major act on the black theater circuit (TOBA), known for her affecting voice and eye-catching stage attire. After recording for Columbia in 1923, Smith’s career skyrocketed. The timing of her first release, “Down Hearted Blues,” was well placed: 78s by female African American blues singers (the Blues Queens) were peaking in nation-wide popularity. By the mid-1920s, Bessie Smith was the most popular and well paid blues singer around.

Besides their incredible music, the Blues Queens were important in another way. Many scholars--most notably Hazel Carby and Angela Davis--have contended that the Blues Queens offer an uncommon glimpse into the social and emotional worlds of black women during the 1920s. Working class black women were one of the most marginalized groups within American public culture during the first decades of the twentieth century. The African American artists, actors, leaders, and writers who were able to publish or publicize their work were overwhelmingly male and middle-class. Consequently, the recordings of Smith, Ma Rainey, and Ida Cox are some of the few places where we can still hear black women speaking about and to the lives, thoughts, feelings, and concerns of other black women during this period.

When Smith came to Austin in 1931, she was facing enormous professional obstacles. Vaudeville had been declining since the late 1920s, as new “talkie” sound films took over its theater spaces and audiences. The 1929 Depression sealed its fate and simultaneously began to devastate Bessie Smith’s other main lifeline, the recording industry. By the early 1930s, Smith, who had been one of the best paid African American performers of the 1920s, was making a fraction of what she had just a few years before.

Smith’s tour through Texas in late 1930 and early 1931 was a consequence of these increasingly challenging circumstances. According to her biographer Chris Albertson, the singer had sworn a few years before that she would never perform in Texas again.1 Her continued popularity on the stages of the South, as her gig opportunities in other places faltered, forced her to play in Dallas, Houston, Beaumont, Austin, San Antonio, and Cuero. 1931 proved to be an incredibly difficult year for Smith. A handful of months after her Texas tour, her revue broke up in West Virginia after she was arrested for public drunkenness. In December, Columbia dropped her from its roster, as even its most lucrative artists sold fewer and fewer copies.

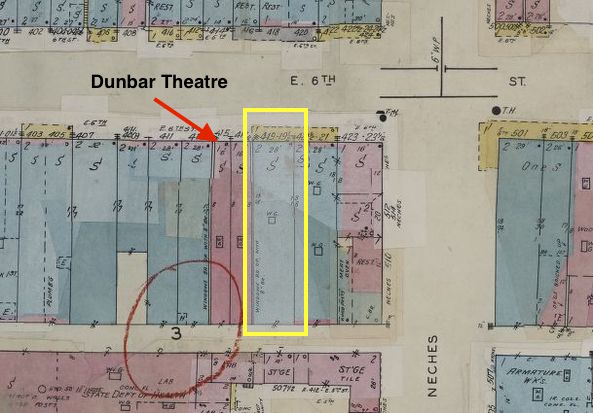

The Dunbar Theatre, where Smith and her revue performed for a “Midnight Ramble,” was on 6th street downtown between Trinity and Neches. The advertisements for her performances on February 16 and 20 announced that they featured a “special arrangement for white people.” Although the Dunbar was a black theater, white Austinites could and did attend performances there. We don’t know exactly what this “arrangement” was, but it probably entailed a special segregated section. The Cotton Club, a black dance hall on 11th street during the 1930s and early 1940s, separated the “white” and “black” areas of its dance hall with a rope. Access was a racial privilege in Texas during Jim Crow: African Americans were continually denied entrance to most spaces, while white Texans could open any door they chose.

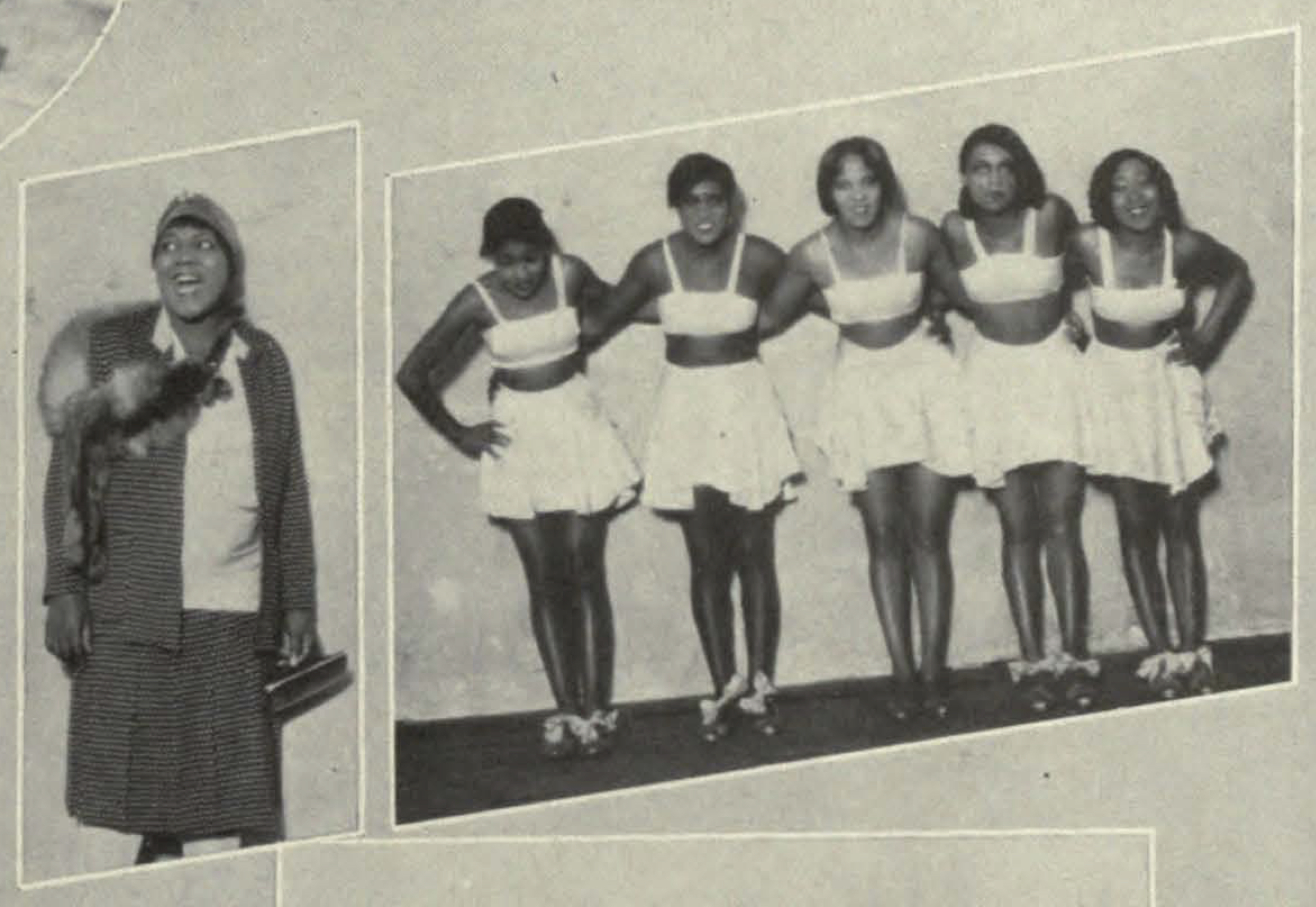

Cactus Yearbook, 1931 (Texas Student Media, University of Texas at Austin).

We know that UT students attended Smith’s performances, since pictures of the famous singer and her chorus girls appeared in the university's 1930-1931 Cactus yearbook. These photos, along with some record store ads for Bessie Smith 78s, give us some indication that the Blues Queens had a cross-racial audience in Austin, although their white listeners may have been quite limited in size. Seen from a different perspective, ads in the Statesman and an appeal to white theater-goers also could have been a sign of trouble. The Dunbar closed in 1932, so its atypical appeal across the color line may have been a last ditch strategy for a struggling venue.

Before her show on the 16th, Smith sang live on KUT, the city’s only radio station at the time. In the 1920s and 1930s, radio music performances were advertising. Singers and bands often broadcast on local stations while on tour, hoping that listeners would buy tickets to their show. And, although her voice on the Austin ether was lost as soon as she was finished, Bessie Smith’s 1931 broadcast was an unrecognized milestone in KUT’s long history.

Besides Smith, the Dunbar only appeared in the pages of the Statesman two more times, when it advertised the next year for a performance by another Blues Queen, Elzadie Robinson, and the now legendary tap dancer, Bojangles (Jim Robinson). These two sets of performances compose the entirety of Austin newspapers’ coverage of the Dunbar. Unfortunately, as this indicates, documentation of the theater is quite scanty.

We can still draw important clues from these two sets of performances, however. Although it is unclear how frequent acts came there, we do know that the Dunbar hosted touring black vaudeville acts at the beginning of the 1930s. Since Austin did not have its own African American newspaper at the time, it is very possible that advertising in print was rare, not performances. Futhermore, Bessie Smith and Bojangles's appearances may have been part of a decades long series of black vaudeville acts in the city. The Dunbar was the only black theater in the capital in 1931, but there had been two during the previous decade (the Dunbar was named the Lyric before 1929). The other, the Lincoln, had closed at the very end of the 1920s, mostly likely a victim of the Depression. Although a lack of evidence at this point prevents us from firm conclusions, it is possible that both the Lyric and Lincoln featured African American vaudeville, since theaters in this period typically showed movies and hosted live acts.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1935 (Volume 1).

As such, the Dunbar represented a crucial, if disappearing, side of Austin’s interwar African American entertainment world. The Lyric/Dunbar and Lincoln were probably Austin’s venues for touring African American revues and vaudeville shows, one of the most visible and popular sources of music in the United States in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Vaudeville acts, who travelled extensively and had heavy ties to Tin Pan Alley, would have been the Austin black community’s major link to national pop trends, connecting the small city to styles, sounds, and hit songs from the rest of the country (including the South). The blues, as a song form, developed within black vaudeville roughly between 1900 and 1910. Austin likely heard its first song-form blues from a traveling African American vaudeville performer or from one of the many white imitators, like Sophie Tucker, who created a “blues craze” on mainstream stages in the late teens.

The Lyric/Dunbar and Lincoln were cultural counterpoints to the Royal Auditorium, which hosted the other major commercial form of African American music, dance bands. Both local and touring orchestras, like those of Earl Hines, Jimmie Lunceford, and Louis Armstrong, played for black dancers at the Royal Auditorium (renamed the Cotton Club in the 1930s). These black Vaudeville and black dance band venues only had a short window of overlap in Austin, however. The Royal Auditorium opened in 1929 and the Dunbar closed in 1932. Together, they represent one of the major cultural shifts of the first half of the twentieth century: the eclipse of vaudeville by jazz orchestras as the center of American popular music.

Finally, the Dunbar was also a remnant of a disappearing cultural and racial geography of Austin. Before the 1930s, African Americans and Mexican Americans had lived in areas across Austin. Consequently, the Lyric and the Lincoln were located in the commercial heart of the entire community, 6th street downtown. It was only after the 1929 City Plan designed a strictly segregated city that black and Mexican American businesses were compelled to open in or re-locate to East Austin. The African American theater that followed the Dunbar exemplifies this. The Harlem theater, which opened a few years after the Dunbar closed, was on East 11th street, not downtown.

- The reason is unclear in Albertson’s book, but it was likely due to experiences of discrimination and racial violence in Texas. Many other African American musicians described the incredible danger they faced traveling and playing in both rural and urban Texas in the 1920s and 1930s.↩