In this post, we are going to expand the geographical field a bit here and put a spotlight on Houston in the 1950s. As home to Peacock Records and Gold Star studios, Houston was one of Texas’s major music centers in the 1950s. Knowing what was going on in H-town will provide an important contrast to Austin during the same period (the subject of our next exhibit).

We also want to use this space to pay tribute to an important jazz innovator, Alvin Fielder, who passed away in January of this year. Mr. Fielder was most well-known for his pioneering role in free jazz drumming during the 1960s; as a founding member of the seminal social-music group the AACM; and as one of the most important voices in the jazz avant-garde in the South since the 1970s. In the 1950s, however, he lived in Houston, where he attended Texas Southern University. In addition to his importance as a musician, Mr. Fielder was also a keen observer of jazz history and a rich conversationalist. He spoke to me while he was in Austin performing at the February 2016 No Idea Festival.

What follows are excerpts from our dialogue about Houston and R&B’s historical connection to jazz.

1950s R&B as a Jazz Laboratory

AF: I can go back to the rhythm and blues bands of the forties, fifties, early sixties—most of the sidemen were bebop musicians. You think of the rhythm and blues of today—the musicianship just isn’t there, not really. And you look at the trumpet players, saxophone players, they’ve got all the facility in the world, but they haven’t created anything since the sixties.

MJS: What do you think…

AF: Caused it?

MJS: Yeah, how do you think musicians were educated before?

AF: Mentorship. Mentorship—the best way. Because this music, it was like magic. You could say it just sprung up after slavery. There was no roots for it. African musicians were brought over here to slavery and I think the American experience really had a great deal to do with it. As Art Blakey said, “only in America could this music have been created.”

I can remember when I was in high school: I lived in a very nice neighborhood, but going to school I had to pass through some other neighborhoods. I walked to school sometimes—I was usually driven to school—but you had those joints and those dives and the music was playing early in the morning. You would hear it; it’s in the air. And then, of course, the jukeboxes had jazz AND rhythm and blues on it. You’d get Charlie Parker being played, Dizzy Gillespie, all bebop stuff. Dizzy Gillespie’s big band mainly, Charlie Parker’s quintets. I didn’t hear any Thelonious Monk, though [laughs] … I didn’t hear any Bud Powell. Some other players: Earl Bostic’s music and stuff. BUT when you think of the Earl Bostic band, think of it, think of who came out of that band. Do you know who came out of that band?

MJS: Coltrane came out of that band.

AF: That’s just one. Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Jimmy Cobb, G.T. Hogan, a bass player from Washington. He had all jazz musicians. Louis Jordan’s band was the same way. When you think of B.B. King’s band, it was all jazz musicians. Jymie Merritt was in that band, George Coleman, Charles Lloyd. Think of Ray Charles’s band: all jazz musicians. Ray Charles plays great alto. He’s recorded two or three tracks … he really sounded great on alto. His piano playing was good—he sounded a lot like Nat King Cole at first.

Jazz was the music. George Adams came through rhythm and blues. Sam Rivers, Hank Mobley, all those guys came through rhythm and blues. It was different. It’s not like the rhythm and blues today. It started changing in the sixties: lesser musicianship.

I can remember when I first saw B.B. King’s band. All the bands would come to Meridian at least once a month. B.B. King would come through once a month … Ray Charles, Big Joe Turner, Gatemouth Brown. There was this route. I used to talk to these guys and the first person I talked to was Jymie Merritt with B.B. King and he was the one who told me about Clifford Brown. Now this is about 1948, 1949. He told me about Philly Joe Jones and he told me about Jimmy Smith’s drummer … those were the musicians he was talking about.

There was this East Coast band, the Joe Morris band. Guess who was in it? Philly Joe Jones, Percy Heath, Johnny Griffin. All the great jazz musicians played in rhythm and blues bands except Jackie McLean and Sonny Rollins, probably. Think about it: it was a great starting factor because the rhythm and blues bands were swinging. They don’t swing any more. Rhythm and Blues, of course, turned into rock later on. There’s a difference in the rhythms, though.

MJS: What was your experience in rhythm and blues bands?

AF: Well, I was born in Meridian, Mississippi. Are you familiar with Lovie Lee Watson? He was born there. I played in his band. Lovie Lee and his Funky Three. That was the name of his group. Lovie Lee went on to play with Muddy Waters.

A lot of great musicians came out of Meridian. Big Jimmy Cole called his band Jimmy Cole and his Mighty Rockers. However, they were playing jazz. Jay Crosby: tenor player from Meridian, went into the army. You remember the Pittsburgh Courier, the Chicago Defender? They had write ups on him. Great tenor player. He wound up in Chicago. He played like Illinois Jacquet. Bunky Lane was a white tenor player from Meridian. Sounded a lot like Stan Getz. Do you remember Dexter Gordon … Dexter’s Deck and all that? That’s how Bunky Lane sounded. Great white tenor player. But his father was band director for the Meridian schools. He moved to Hawaii and joined the navy, but he could have gone to New York and really played. You had several drummers from there. You remember Freddie Waits? Freddie was from Jackson. We both started playing around the same time.

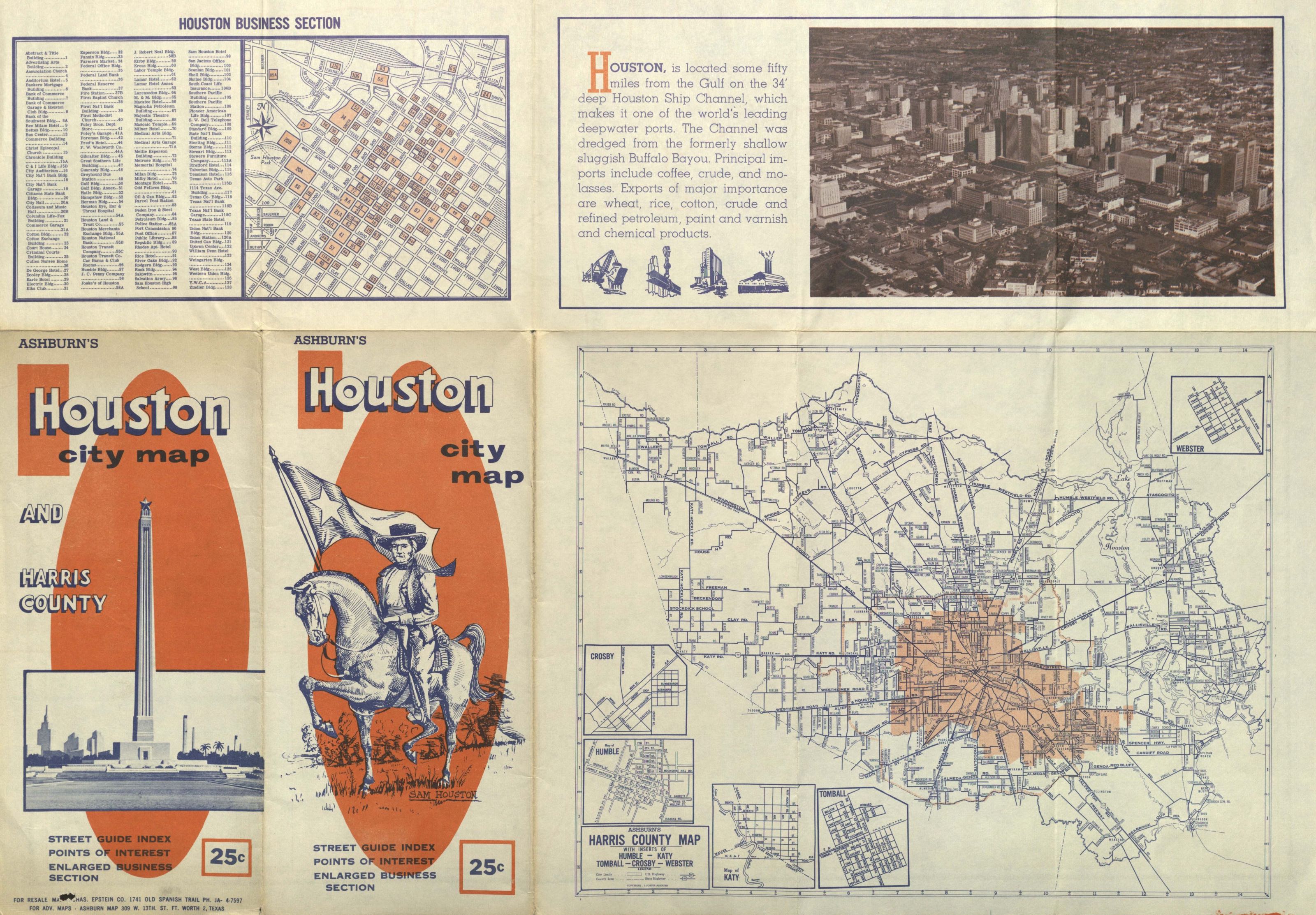

Houston, Texas - Harris County map. 1956. Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries.

Houston

1950s Houston exemplified this deep connection between postwar bebop and rhythm and blues. Mr. Fielder was born in Meridian, MS, but moved to Houston in 1953/1954 to pursue a pharmacy degree at Texas Southern in the 3rd Ward. At the time, Houston was quickly becoming one of the most important centers of R&B in the nation and Don Robey’s Peacock Records became a center of gravity for talented African American musicians across Texas and the South. Although in his late teens, he quickly integrated himself into Houston scene. He became the drummer for Pluma Davis, who led the house band at the Eldorado Ballroom, an elegant, middle class black dance club at the corner of Elgin and Dowling. Davis’s band backed a number of Peacock Records’s artists in the 1950s and was largely made up of jazz musicians.

Amongst many things, Mr. Fielder discussed the musical richness of Houston’s Third Ward while he was there. Bebop was being played everywhere, he remembered, and the city was full of talent. Some musicians, like Arnett Cobb, already had a significant career and had returned home. Others went on to record for important labels and became (or were already ) part of the documented national—and international—story of jazz history: Don Wilkerson, Henry Boozier, Joe Sample, G.T. Hogan, Jimmy Harrison, Joe Curtis, and Richie Goldberg.

Fielder noted that there were also significant local players who never received any recognition outside of Houston. J.D. Norris, a tenor saxophone player who played like early Sonny Rollins; Dickie Boy Lillie, who was Billy Harper’s teacher; Alexander Sample (Joe’s brother), piano; and Perry Deal, a pianist who reminded Fielder of Muhal Richard Abrams and who he declared “was the most creative piano player to come out of Houston.” John Browning, who Fielder played with in Pluma Davis’s band and in Browning’s own quartet, was most well known for playing trumpet with B.B. King’s band.

(note: the sound quality is not perfect, since the interview took place on a backyard porch and one can also hear grackles, the screen door, and neighborhood noise.)