Most of Austin’s orchestras in the 1930s remained close to home, never going much further than the city limits. This was especially true for bands made up of university students, who were attending classes as they performed on campus for extra spending money and fun. Student musicians typically had little time for the slow travel that Texas’s rough intrastate roads required before the advent of the highway system. The groups that toured regionally, like the bands of Fred and Steve Gardner, usually stayed within a few hundred miles, only making it to select towns and cities in Central, South, and North Texas.

One major exception, however, was the band of Clarence Nemir, which not only left the state, but did four tours of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East between 1932 and 1935. Nemir’s was one of the first, if not the first, Austin pop music bands to go global—to tour beyond the United States and to bring a Texas sound to international audiences.

Like most of the capital’s groups from this period, there is little to go on when trying to reconstruct the music of the band and their trips. All that seems left about the journey is a handful of short newspaper articles, an internet obituary, and some short remarks in an oral history. The orchestra never made it into a recording studio and there is only one partial letter by Nemir himself.

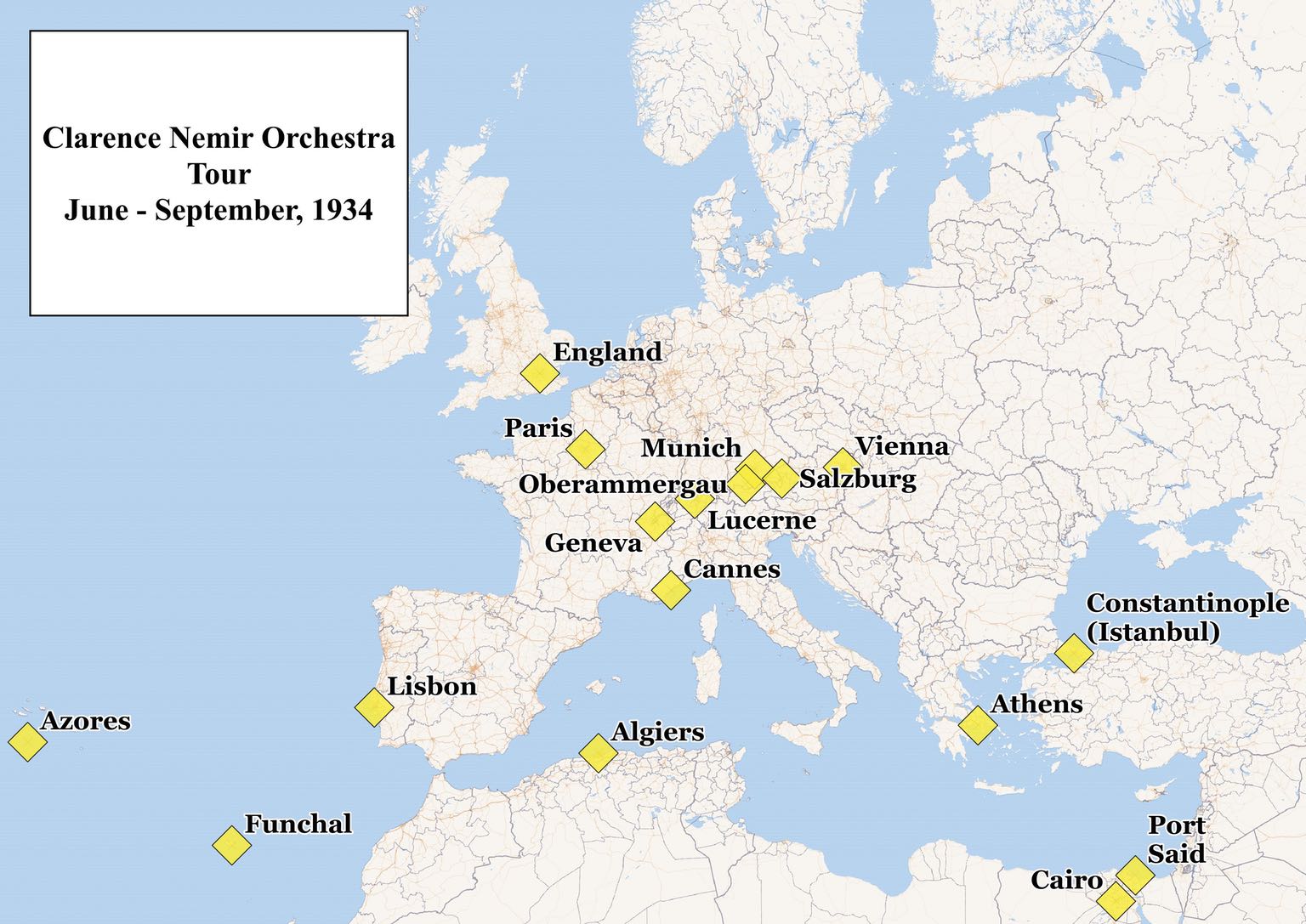

The first tour—undertaken by the bandleader, Jack and Gertrude Andrews, Lee Mayfield, H.L. Bromberk, and Zeb Rike—was not an independent trek, but part of an organized group trip by “Leisurely Tours” alongside faculty, other students, and some Austin residents.1 We know that their 1934 journey was taken alone, however, and they left Austin for New York on June 1st. From there, they sailed on the M.U. Lafayette for Le Havre, France. After landing, they moved to Paris, where they stayed for Bastille day and Nemir earned extra money by acting as a social agent for American tourists.

Everyone on the trip was a UT student (one was a member of the Longhorn marching band and another on the yell team) and Nemir and one other bandmate, Alvin Newbury, took advantage of their European sojourn to take classes at the Sorbonne (Paris) and Marburg (Salzburg). After Paris, they zigzagged across Western Europe. They first travelled Southeast, playing in Lucerne, Geneva, Munich, and Oberammergau. They got a gig at a casino in Austria and then returned north to Western Germany for a trip up the Rhine river. Finally, they performed on a Mediterranean cruise boat, visiting Lisbon, the Azores, Funchal, Algiers, Cairo, Port Said, Constantinople, Athens, and finally Cannes. At some point, they also toured England. Apparently, Nemir was most impressed by Spain, which he believed was in the best economic shape in Europe during the transnational economic Depression (although it isn’t clear when they played there). The Spanish must have liked their band too, for he signed a contract to play the following summer in Barcelona before they set sail back for Austin in late August.

In 1935, the orchestra, this time comprised of Clarence and Fred Nemir, Earl Cornwell, Edwin Gage, Lucille Mick, and Hayden Curtis, returned to Europe to fulfil their engagement in North Spain. Their boat left North America months before their gig, however. During the preceding summer and early Fall, they took advantage of their Spanish contract to both get out of the Texas heat and to perform in some other places on the continent. They then played dance music in Barcelona until late November, when all but one member returned to the US. Mick stayed to study “French, Spanish and Italian and coaching with one of the leading dance masters of Spain.”2 While on the job, Nemir wrote a letter back home to a journalist for the Austin American newspaper. They were having a very pleasant time in Spain, Nemir reported, but his appraisal of the Spanish economy was wrong: they wanted to pay you in flattery since they were short on cash. Despite this lack of compensation, they were receiving a great deal of publicity and performed at all the “important night posts in Spain.”3

One of the members, Gene Hall, would go on to be a pioneer in jazz education—he developed the first college program in jazz in the United States in 1947 at North Texas University in Denton. In 1991, Hall conducted an oral history and recalled one part of the Nemir orchestra’s experience in Spain.

After being approached by the Ford Motor Company in Barcelona to perform on a local radio show, the band

started playing this program. Things were going fine...but about fifteen minutes into the program, we noticed that people began to frown...then we learned that it was a one-hour program, and most of our arrangements were about three minutes long, made for dancing. So we had only enough music for thirty minutes. The rest of our arrangements were over at our place...the leader says, “Don’t worry. Don’t worry.” The producers were chewing their fingers...when we ran out of music,...he said, “Let’s play ‘Moonglow.’” We’d been playing every night for the last six months, so we knew it was no problem...so we just played arrangments from memory. At the end of that program those Spanish people thought we were the greatest musicians. They ran around kissing everybody.4

The Nemir band was part of the second wave of American jazz and dance musicians who had appeared in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. After the now oft-cited performances of the proto/early-jazz ragtime orchestra of James Reece Europe in France during the First World War, a number of musicians performed in Britain and on the continent in the late teens and throughout the 1920s. These bands were significant groups and included tours by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in England in 1919, Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra from 1919-1921, Sidney Bechet from France to Russia between 1925-1928, Paul Whiteman in 1926, and Sam Wooding and his Chocolate Kiddies 1925-1927 and 1928-1931.

Although they already had been obsessed with the idea of jazz since at least 1918, these tours made a huge impact on Europeans. These concerts were crucial to the spread of American pop music to the rest of the world. Occurring over the course of a decade, they were the first in-person encounters that Germans, British, French, and Turkish listeners and musicians had with American performance idioms and the sound of live American jazz/dance music.

Nemir’s orchestra participated in the current of musicians that came after this period of first contact. He travelled across the Atlantic during the moment when some of the major innovators who would decisively influence the music of the 1930s and 1940s first appeared in Europe, most importantly Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Around the same time as Nemir’s trips, African American musicians like Coleman Hawkins and Benny Carter moved to England or Scandinavia to escape American racism and economic discrimination. In Europe, there were fewer personal restrictions and they could often be compensated in a way that their stature as musicians deserved (many more black musicians would moved to Europe in the 1950s for the same reason).

Nemir may have been the first Texan territory band to appear in Spain, France, Austria, Egypt, Greece, and the other places they visited. If they absorbed any of the unique sounds of Texas dance and vernacular music from the period—most notably represented by Alfonso Trent or Don Albert—they carried it with them to these new, far-flung audiences. They did so as the Depression rocked these countries and democratic governments began their retreat in Europe. In this context, they were able to play in some place that black Americans could not. Their 1934 appearances in Germany—where the Nazi party had recently taken over the government—occurred as the official rhetoric against jazz and black American music became increasingly harsh, denigrating, and violent. Thus, they were able to appear in Munich, Oberammergau, and along the Rhine; black musicians like Coleman Hawkins and Duke Ellington would be denied entry to Germany entirely in 1935, just a short time afterwards.