The “Germans” and the All University Dances, 1901-1946

Venues for the “Germans” and the All University Dances

1910s-1929

The Original “Germans”

Knights of Columbus Hall

Prints and Photographs Collection, di11390, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Prints and Photographs Collection, di11391, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Prints and Photographs Collection, di11393, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

1923-1930

All University Dances

Women’s Gym

1930-late 1950s

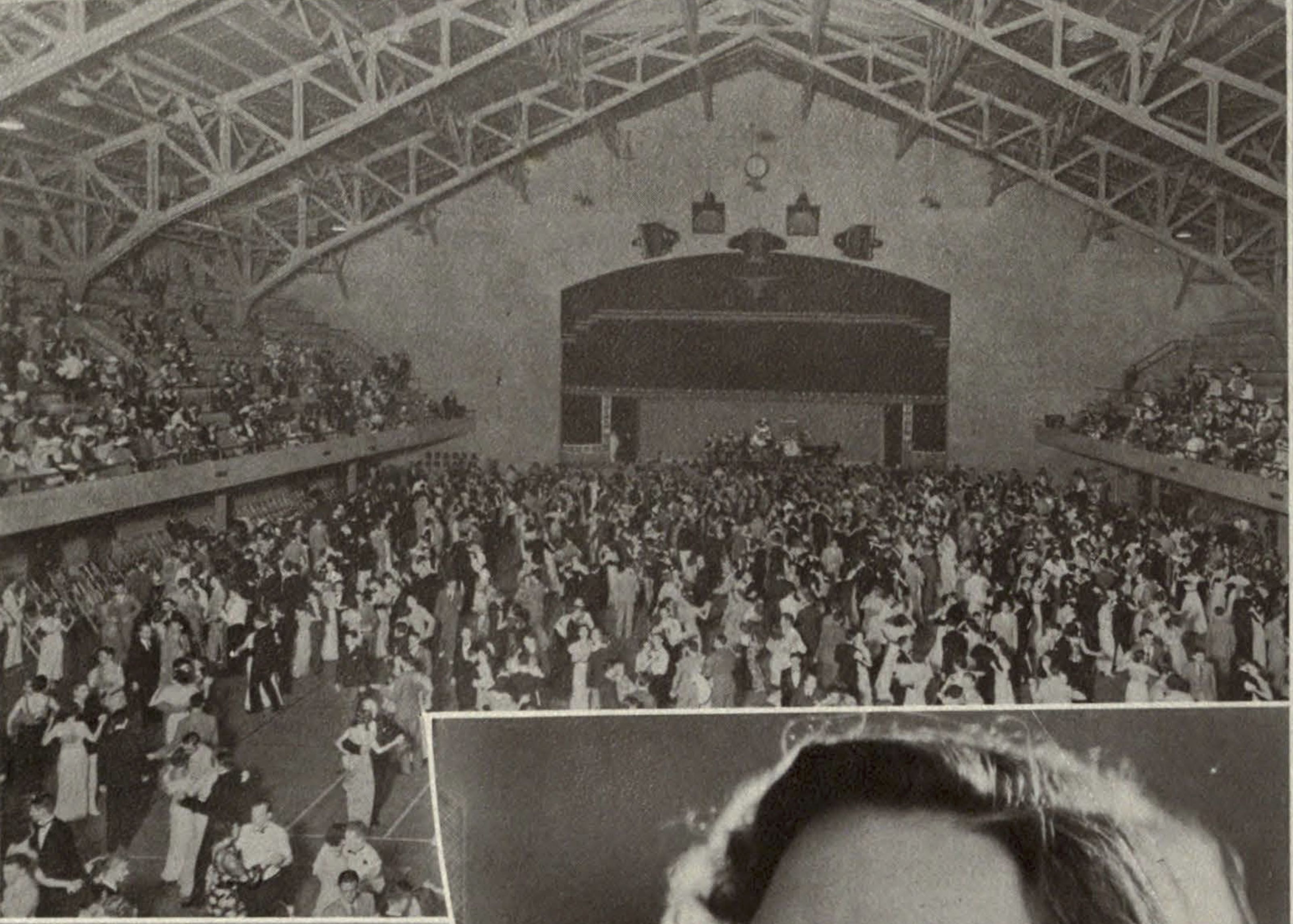

All University Dances

Gregory Gym

1933-late 1950s

(smaller) All University Dances

Texas Union Ballrooms

Since at least the beginning of the twentieth century, dances were major social events in the lives of University of Texas students. What became a decades-long tradition began as early as 1901 when the German Club, a collection of fraternities, started to organize dances at Protection Hall on 8th Street downtown. In their first decade, the “Germans” were often played by the band of William Besserer, a professor at UT and the leader of the Varsity band. Besserer worked with a range of late-19th and early 20th century popular music. At the Germans, he played recent Tin Pan Alley tunes like “Love Me and the World is Mine” and operetta pieces like “The Merry Widow” waltz. On at least one other occasion, he orchestrated the music for the Varsity Minstrels, one of the university’s blackface shows.

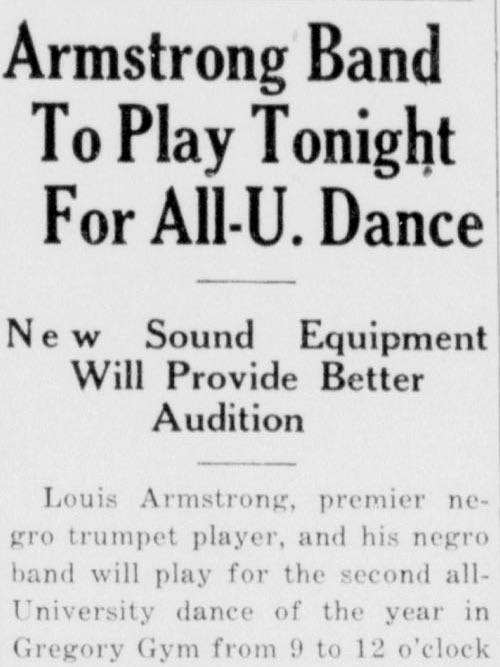

The “Germans” both preceded and participated in the wider transformation in American dancing in America in the first quarter of the twentieth century. In the early 1910s, Irene and Vernon Castle initiated a nation-wide craze for African American- and ragtime-inspired social dances like the Turkey Trot and Grizzly Bear. By the late teens, the “Germans” had moved to the Knights of Columbus Hall and had clearly stayed apace of new trends in the popular music industry. Only a year after the Original Dixieland ‘Jass’ Band made the first jazz recordings in 1917, they began to hire local jazz groups, including Shakey’s Orchestra, Jimmy’s Joys (who made numerous recordings in the 1920s), Steve Gardner , and the Fire Hall Five.

Around the same time, small gatherings started on campus in the Women’s Gym , where female students performed and danced to a piano. They were originally chaperoned by the Dean of Women (men could only attend the last 20 minutes), but soon they were taken over by students, who hired dance orchestras. In 1923 these events became the “All University Dances,” since they were open to students excluded from the “Germans,” and they were officially authorized by the Student Assembly in 1926. The German Club dissolved in the 1929, but students continued to use the term “German” for university dances.4

After the demise of the German Club, All University Dances continued to take place in the Women’s Gym. Once Gregory Gym was completed in 1930, they moved into this new, more modern and spacious dance floor. The main venue for the dances changed again after the Texas Union opened in 1933. After this point, the Union became the main ballroom for regular “Germans,” although Gregory continued to be the site for dances with popular touring acts. In the first half of the 1930s, All University Dances occurred off campus as well: between the long sessions in the Fall and Spring, the Stephen F. Austin Hotel put on summer “Germans” on its rooftop garden amidst the blazing heat.

By the first years of the Depression, the “Germans” had transitioned from informal events run by students to dances administered by the university. All-University Dances represented the growing role that UT took not just in providing education to young Texans, but also their entertainment and lifestyle. It also allowed the university to more closely monitor and control these social events, since large numbers of journalists, clergy, and parents condemned jazz as primitive and morally dangerous in the 1920s.5 This continuing fear of popular music was especially clear in the way UT attempted to regulate where its female students went—women had to get permission from a university Dean to attend any dance not on the official calendar in the 1920s and 1930s.

UT as a Center for Dance Music and Swing

During the 1930s and early 1940s, the University of Texas was probably the most significant supplier of live pop music in Central Texas (and one of the largest in Texas as a whole). It was also the biggest employer of dance orchestras in the region. During the first three quarters of the decade, it was Texas Union that played this role. Between 1937 and 1945, however, it was the university’s fraternities, sororities, and clubs that provided the vast majority of dances.

The greatly expanded audience, space, and resources of the university enabled Austin to draw stars of the music industry consistently for the first time. The city had hosted territory bands from Texas and the Southwest during the 1920s, but these groups were largely peripheral to the national industry. Furthermore, for major bands in Texas, Austin was secondary in comparison to cities like San Antonio, Houston, or Dallas.

The advent of big dances at UT happened just as another important change occurred in the music industry. Over the course of the 1930s, a national touring circuit for dance orchestras began to take shape and major stars began to tour much more widely. As a result, the orchestras of Count Basie , Duke Ellington , Benny Goodman , Jimmie Lunceford , Jan Garber , Hal Kemp , Tex Beneke , Stan Kenton , Dizzy Gillespie , Benny Carter , and Tommy Dorsey all played on the basketball court inside Gregory Gym or in the Union ballroom.

Most dances in the 1930s and early 1940s were with local or regional groups, however, and university students provided a constant supply of gigs. Judging from the ads and articles in The Daily Texan and other Austin newspapers, white bands got a disproportionate amount of employment. Herman Waldman , Ben Young , and the Gardner brothers played an extra-ordinary number of the all-university dances, while local black groups like the Corley Brothers or Johnny Simmons played much more sporadically.

University gigs could easily determine the livelihood and survival of Austin orchestras. Between 1929 and 1933, the university had an official dance orchestra, which received a contract to play every All University Dance for the school year. In 1933-1934, All University Dances paid between $100 and $300, a big paycheck in the midst of the Depression. In 1937, Fred Gardner , who led one of the most popular bands in Austin in the 1930s, claimed that he had “received numerous offers to enter ‘big time’ entertainment with the success of his [recording of “Loveless Love”], but at the time the orchestral field in Austin was exceptionally lucrative and he remained here.”6 These sorts of decisions—on which bands to hire—were important parts of the structural inequalities between white and black bands in Central Texas during this period.

The Decline of the Large Dances

At first, dances were also financially central to the Texas Union, the social and cultural center for university students. During its first four years, the profits from the All University Dances paid for 90% of the Union’s operation costs. This was by design: after its construction, the board of directors planned on the dances providing a continual source of income for the campus center.7 This was possible at first, since the All University Dances drew huge crowds during the height of the Swing craze (1935-37).

Connally’s first point highlights another important aspect of dances at the university: from the mid-1930s onward, a large percentage of student dances were not put on by UT directly, but by affiliated clubs, dorms, and Greek letter organizations. There were dozens and dozens of affiliated groups by the end of the decade and most held a number of dinner dances and seasonal formals. Together, all these groups contributed in making an extensive, if increasingly separate, musical environment in Austin.

By 1943, the Dance Committee at the Union determined that the large All University Dances were no longer successful and recommended that only a few be given a year. Students, they contended, were now most interested in the dances put on by sororities, fraternities, and clubs.9

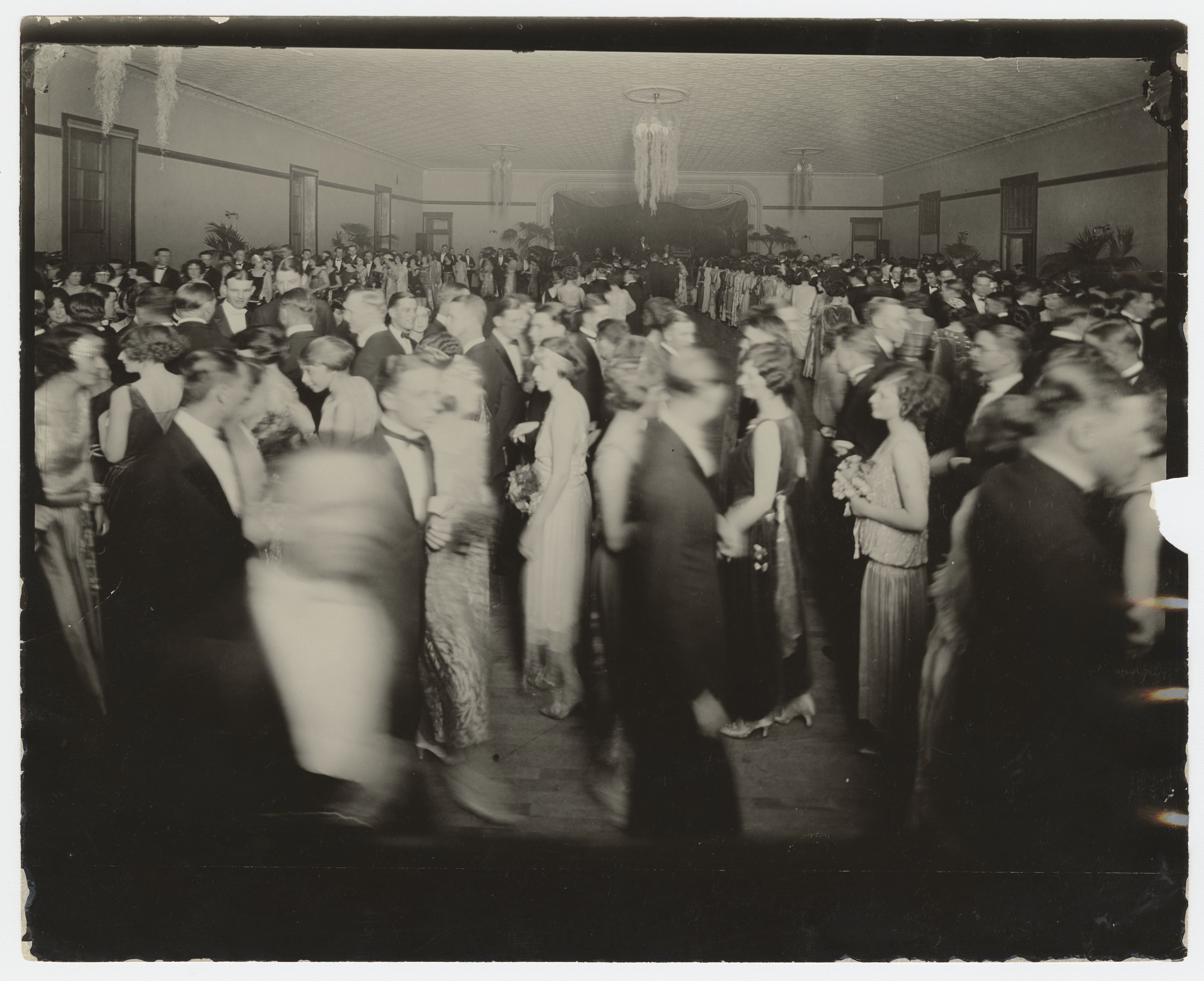

A small UT dinner-dance, probably for a fraternity or sorority, 1937

The Cactus: Yearbook of the University of Texas (Austin: Texas Student Publications, 1937)

At the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s—perhaps as the enthusiasm for the values and ideals of the New Deal declined—the nature of the university’s social life seemed to shift from large, communal gatherings to smaller, more exclusive events amongst specific groups. Thus, between the 1920s and early 1940s, dances at UT moved in a pendulum swing of exclusivity: they began as limited affairs for members of the German club; became big common dances open to all students during the 1930s; and finally retreated back into dances restricted to membership in a club, fraternity, or sorority.

Despite this, the Union continued to hold dances for the rest of the decade and into the following ones. They continued to concentrate on hiring big bands and pop orchestras, despite the collapse of Swing and the incredible evolution of American popular music in the second half of the 1940s. They did manage to book some of the most innovative and progressive large bands of the mid-1940s, including the orchestras of Billy Eckstine (featuring bebop pioneer Charlie Parker, plus Sarah Vaughn, Howard McGhee, Lucky Thompson, and Shadow Wilson), Stan Kenton (the “Artistry in Rhythm” group), and Dizzy Gillespie (with singer Ella Fitzgerald).

Their willingness to move outside the national mainstream seemed to have stopped at bands that specialized in the new, modern language of bebop, however. Surprisingly, the dance committees at the Union seemed to have refused to hire groups that represented the local Central and South Texas re-formulations of the big band: country-inflected Western Swing and Mexican-American Orquestas. And they did not put any groups from the emerging styles of Rhythm and Blues, Rock and Roll, or Honky Tonk country on their stages either. Neither Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys , Gatemouth Brown, nor Beto Villa ever played on campus, despite being Texas musicians who were immensely popular in their home state.

Notes

- Irving Garfinkle, “University ‘German’ Began 30 Years Ago,” Daily Texan (December 14, 1947), 8. ⏎

- “University Girls Had to dance By Themselves Back in 1917,” Daily Texan (December 15, 1934), 5. ⏎

- John Unger, “All-University Dance swings again,” Daily Texan (October 31, 1977). ⏎

- “University ‘German’ Began 30 Years Ago,” The Daily Texan (December 14, 1947). ⏎

- Kathy J. Ogren, The Jazz Revolution: Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 139-161. ⏎

- “Gardner to Play for Next Dance,” Daily Texan June 17. 1937. ⏎

- “Straight Facts About the Texas Union,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- “Letter from John B. Connally to H.J.L. Stark, January 31, 1939,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- “Board of Directors for 1942-43,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎