The Texas Union Project, Texas Oil, and the New Deal

During the bleak and trying years of the Depression, the Texas Union and Gregory Gym were the seats of the University of Texas’s dance and pop music culture. Between 1930 and 1933, the wide open wooden floors of Gregory had provided the primary space for dancers on campus. After opening in 1933, however, the ballrooms of the Union took over as the primary venue for the All University Dances. Once the Union became the center of campus social life, Gregory, with its capacity for up to 10,000 people, held the largest dances and hosted the most prestigious touring bands.

Music was central to Union life. Besides the All University Dances, it also held a variety of other musical events, including smaller dances put on by student groups, fraternities, and sororities; Sunday programs with classical music; dancing classes; and a folk festival. It also provided pianos, phonographs, and a record library for student use. In 1942, the Union’s student music committee set up the “Longhorn Room” in the main lounge, a make-shift cabaret with “tables, candles, and floor shows by student groups.”1

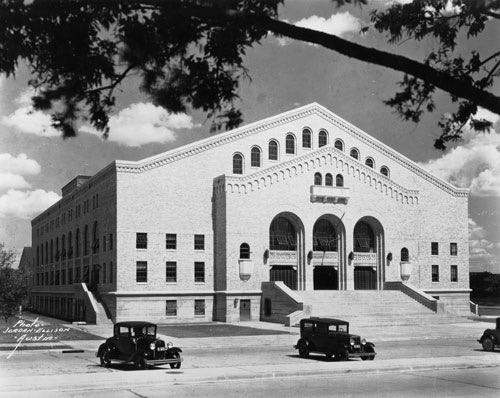

Gregory Gym, 1930s

di04017, PPC: UT - Buildings - Gregory Gym, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

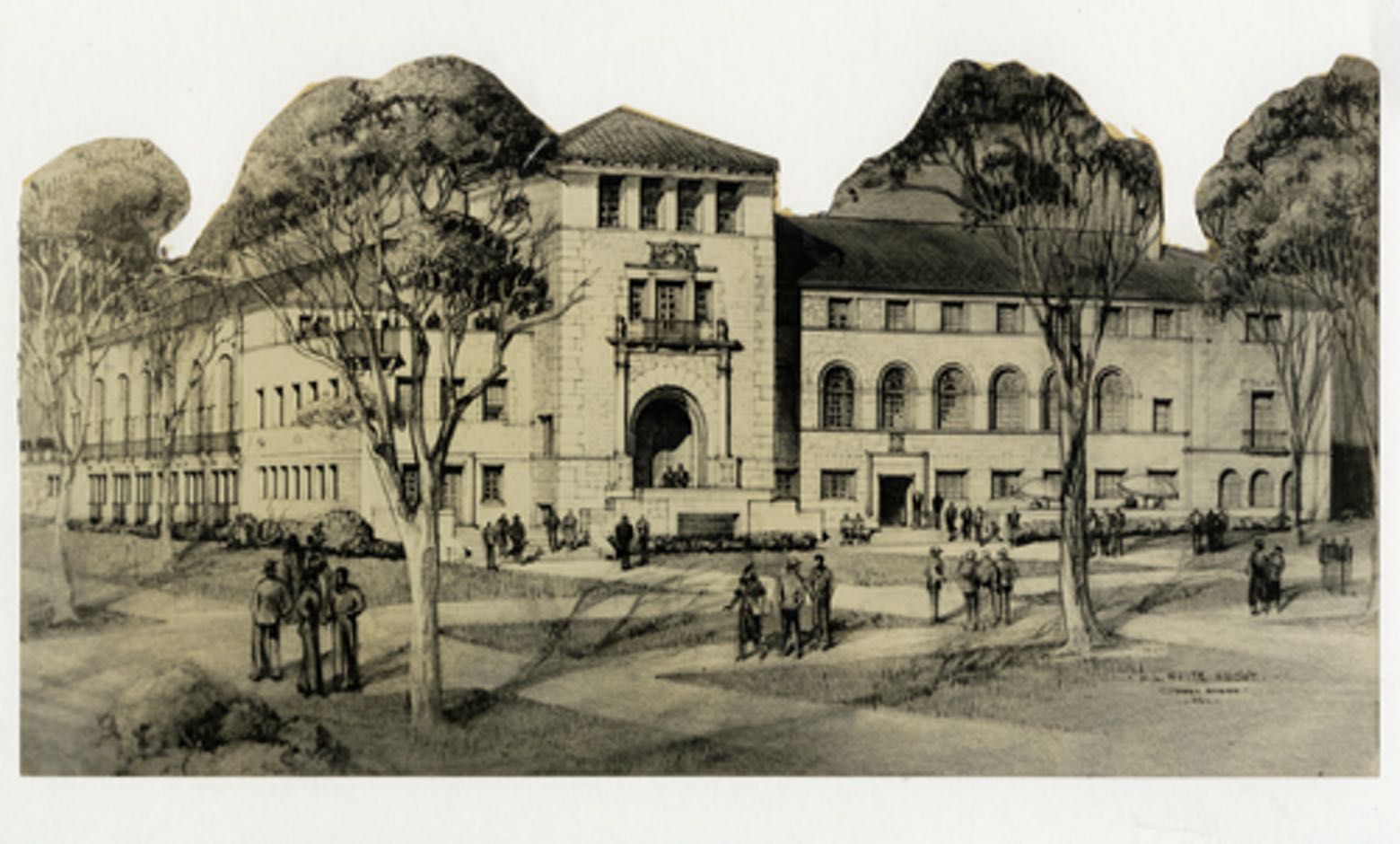

Gregory and the Union were not just connected by music. They were both part of “The Texas Union Project,” a joint venture by the Ex-Students Association and the university’s Board of Regents that also included the erection of a new Women’s Gym (now the Anna Hiss Gym) and Hogg Memorial Auditorium . Gregory was built first in 1930; the Union followed three years later.

The Texas Union, 1936

The Cactus: Yearbook of the University of Texas (Austin: Texas Student Publications, 1936).

The Union Project was the product of UT’s growing ambition to be recognized as a institution of national importance. In 1927, one of its planners took stock of the university’s reputation. It was now among the twenty leading educational institutions in the country, the 4th largest state university, and a “leader among educational institutions in the Southwest,” they observed. Despite this, UT’s facilities were paltry, outdated, and only fit for a country backwater: “our great university has no auditorium except an old wooden barn known as the Men’s Gymnasium , which will hold at a pinch about half the present student body. There is no social center on the campus except another wooden shack, used by the women as a gymnasium during the week and on Saturday night to house the University dance.”2

The quest for new facilities also followed the discovery of oil in 1923 on the lands of the Permanent University Fund in West Texas. The purpose of the fund, which was set up by the Texas Constitution in 1876, was to build “a university of the first class” through ongoing state support. In essence, the fund used the common resources of the state to create a public good: it utilized state land—and by extension, its oil and gas—to support higher education. By the end of the 1920s, the PUF’s wells were producing more than $2000 a day for Texas state universities, making them exceptionally wealthy in the midst of an otherwise widespread financial crisis. Like other elements of Texas society after the discovery of oil, UT dedicated significant amounts of its new cash to raising its status and prestige.

The new Union facilities were meant to reflect the university’s top-level status. Its creators also believed it would be another instrument of education. They hoped the Union would train students to be democratic citizens and better human beings. In their vision, it would provide a “center for democratic fellowship among all students of the university—men and women, rich and poor, engineers and lawyers, athletes and debaters, freshman and seniors.”3 In short, it could provide a place for students of different backgrounds and interests to meet, spend time together, and overcome perceived differences.

Dances were central to the Union’s aspiring democratic spirit during the 1930s and 1940s. Besides sports events, concerts by big bands and dance orchestras were probably the largest regular gatherings of students at UT during these decades. Often referred to as “Germans,” university dances hosted thousands of students. Bringing together a true cross-section of the collegiate body, dances most closely resembled the populist ambitions of the Union Project’s founders. In a 1938 poll by the Daily Texan, two thirds of students reported that they had attended an All University Dance.5 Even during the 1940-41 school year, a period when the dances were declining, 16,761 students attended a “German.”6

The New Deal Context

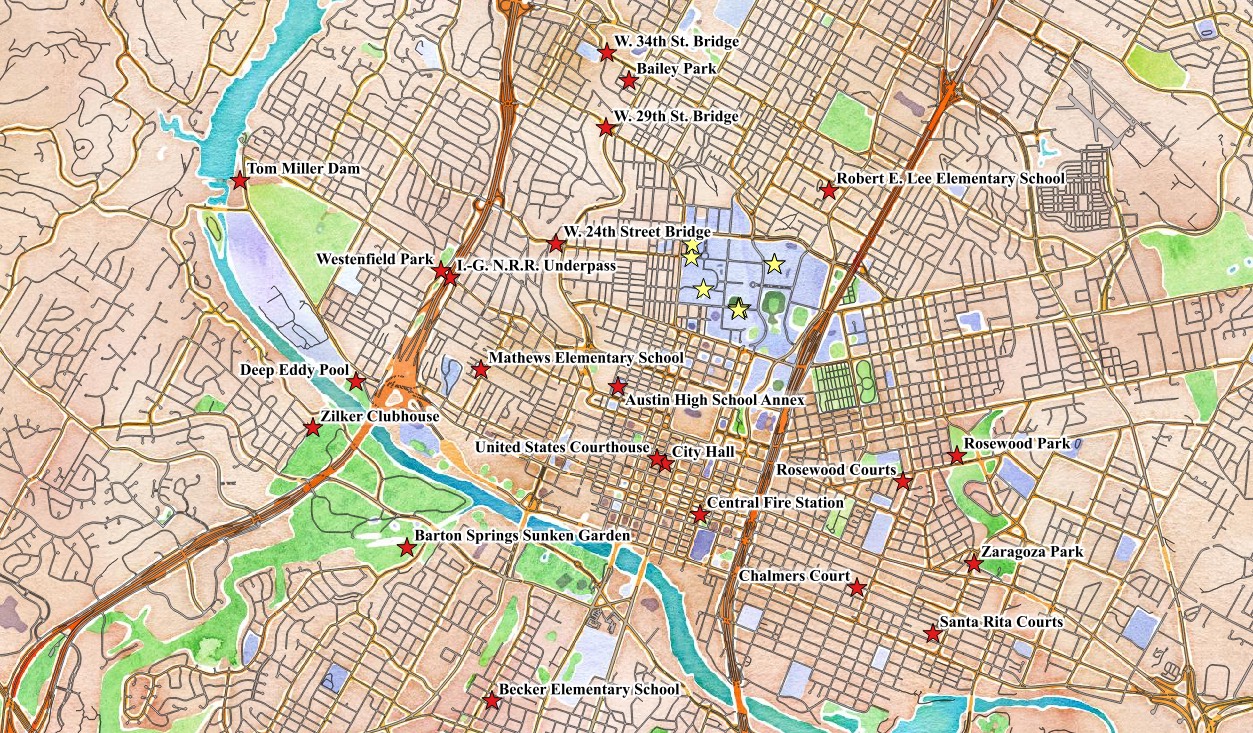

This emphasis on democracy and populism resonated with the larger context of the New Deal. In the face of the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration sought to create democratic fellowship—bringing Americans of different backgrounds together through shared institutions, experiences, and the construction of new buildings, parks, and public art. The New Deal left a large mark on Texas and its activities were all around Austin during the 1930s. The CCC, created the same year as the Union building, provided work and money for young men to build Texas state parks and park buildings (like the headquarters in Longhorn Cavern, cabins in Palmetto State Park and Palo Duro Canyon, or the Indian Lodge in the Davis Mountains). It also sought to make them good citizens by bringing them together in common work and living experiences, like living in rugged camps, forming trails, cutting down live oaks and cedar, and creating facilities out of local limestone.

A number of central structures on UT campus are New Deal products. The Main building and library, the Texas Memorial Museum, the Glen Rose Dinosaur Tracks Display, and five campus dorms (Carothers, Roberts, Andrews, Hill Hall, and Prather) all received funding and/or construction support from the Public Works Administration or the Works Progress Administration between 1933 and 1939. Beyond the campus, New Deal-financed buildings fill the city, from the bathhouse and limestone stair at Deep Eddy Pool to Rosewood Park and the old U.S. Courthouse.

Notes

- “Board of Directors, 1942-43,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- “A Union Project of Texas” (1927), Box 2.325/J25, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- Ibid. ⏎

- “The Texas Union at the University of Texas,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎

- The Daily Texan (May 22, 1938). ⏎

- “Annual Report, 1940-41,” Box 2.325/J26, Texas Union Records, Briscoe Center for American History. ⏎