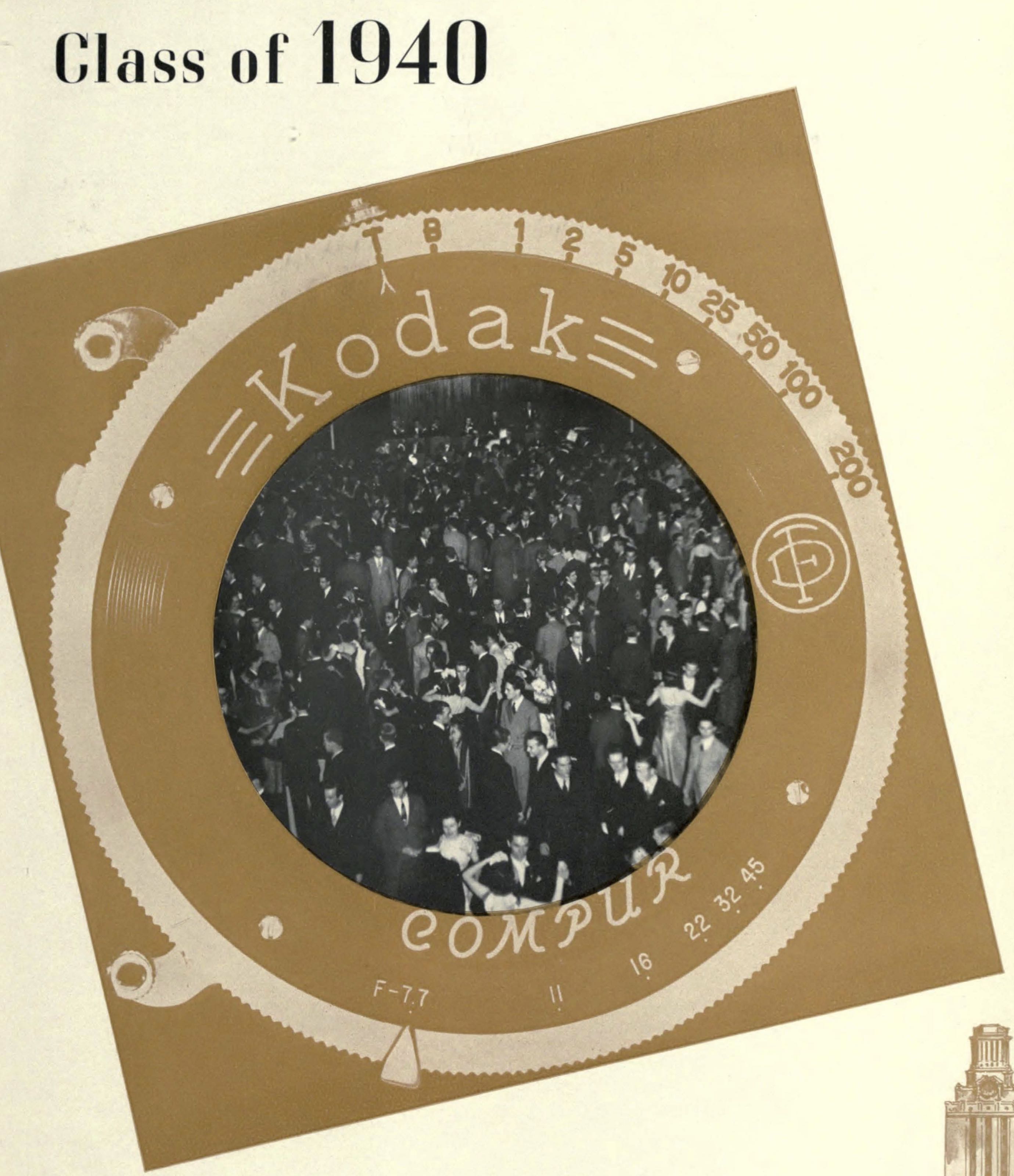

Photos of the All University Dances: An Image Essay

Given their centrality to campus life, one would expect there to be a large stack of surviving photographs from the All University Dances. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. Only a few dozen seem to be available, although it is very possible that considerably more may be tucked away in private collections. All of the images that are currently available appeared in the university’s yearbook, The Cactus. Although some images are quite clear and well-composed, many seemed to have been snapped by amateur student photographers.

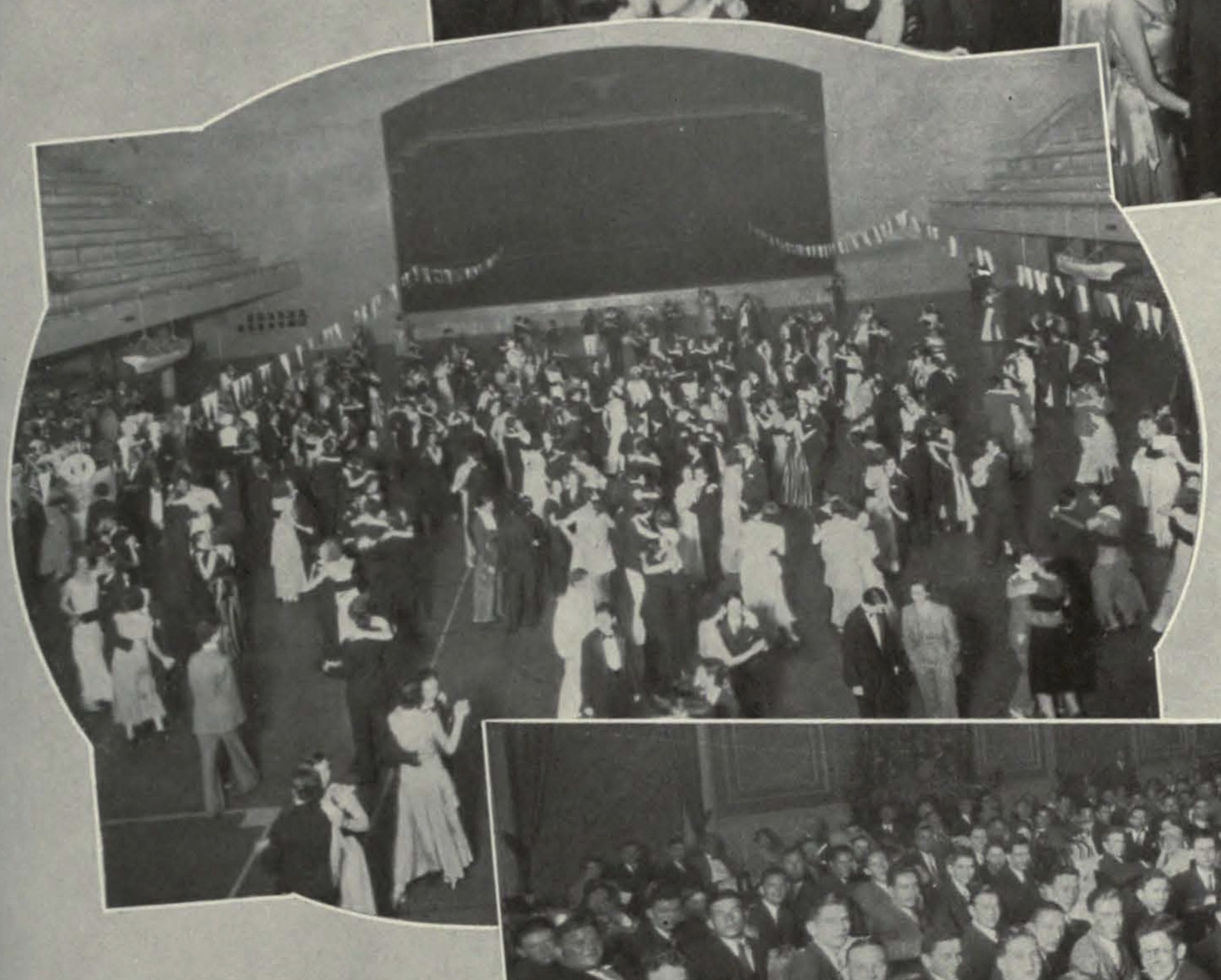

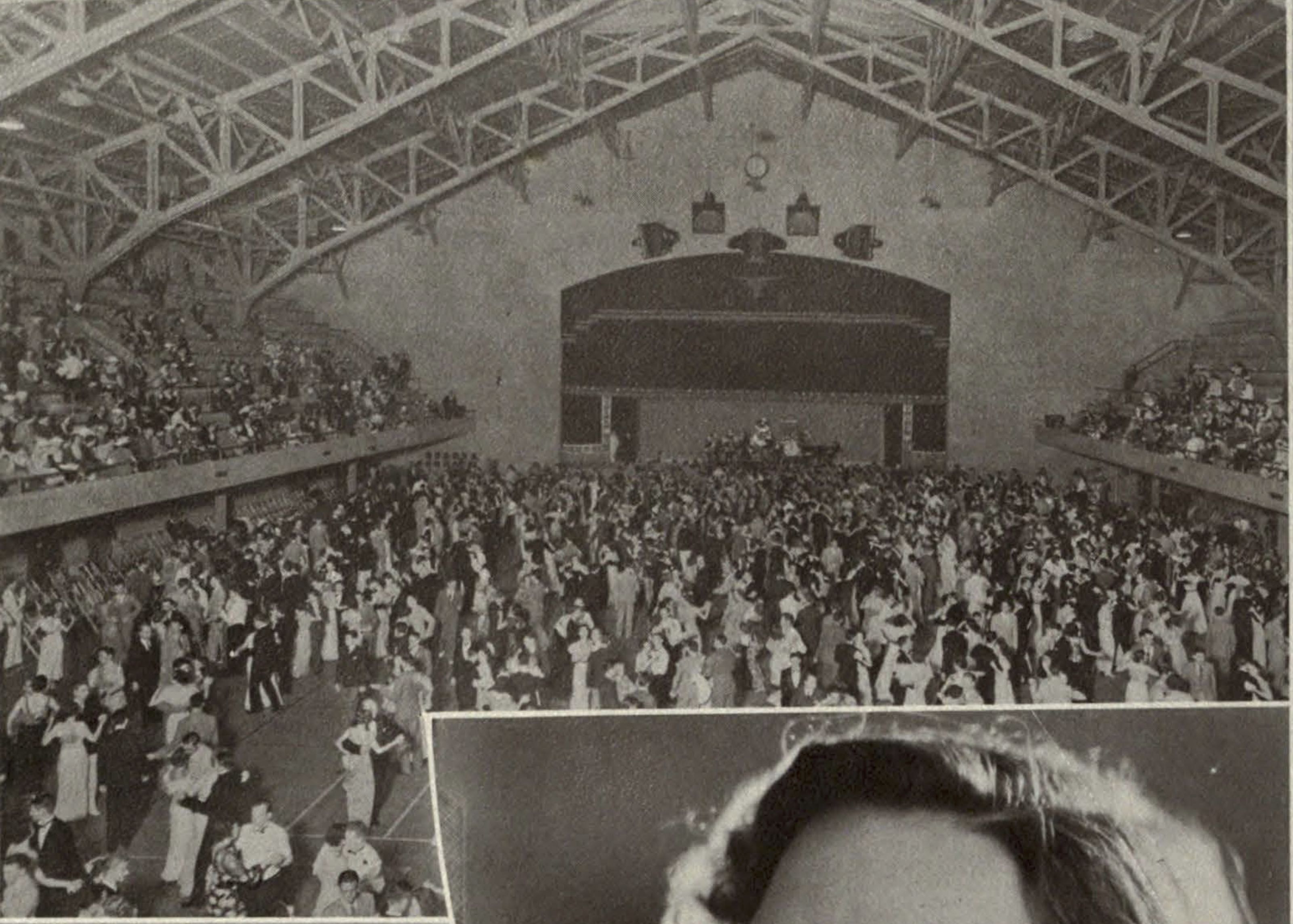

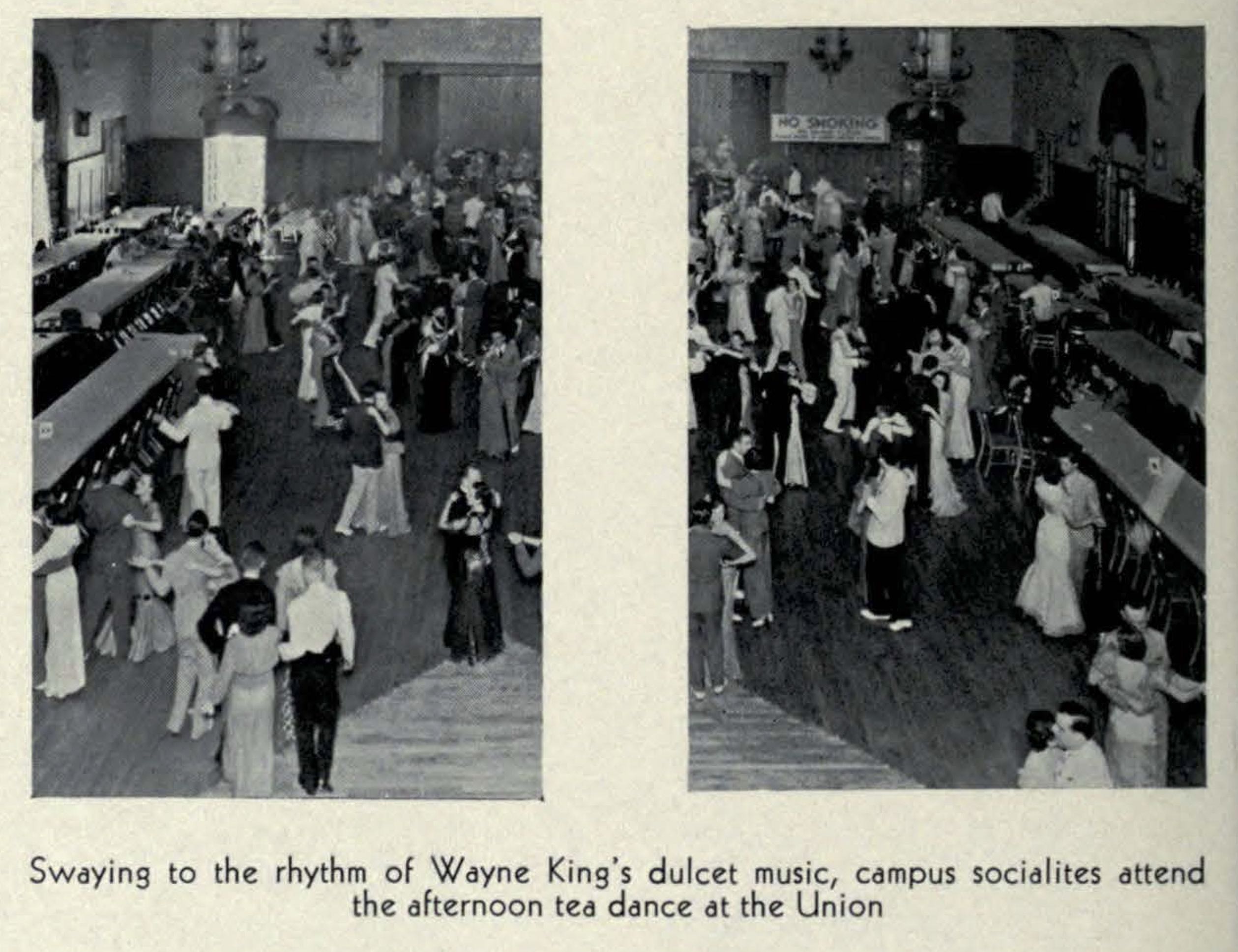

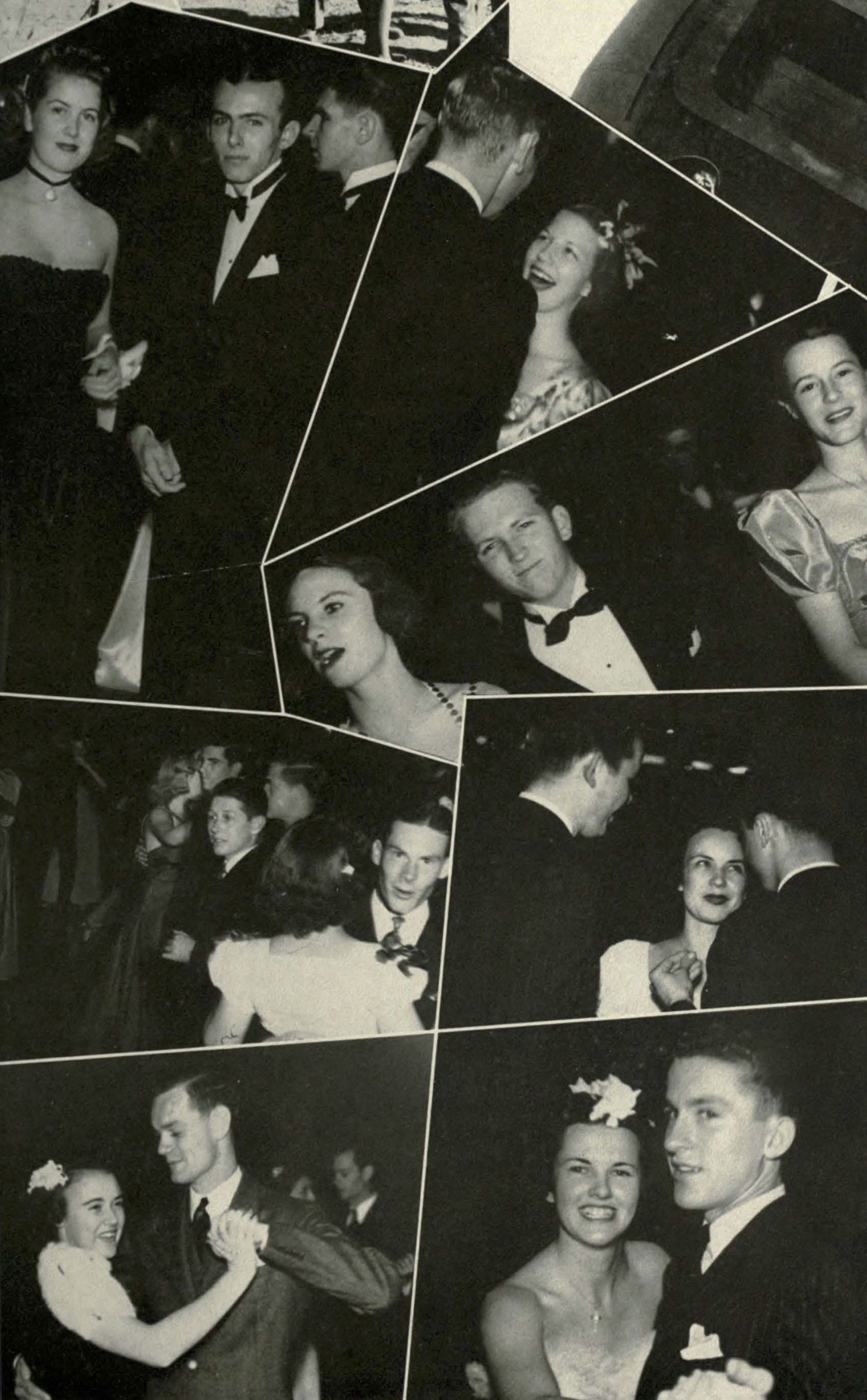

We can gather some information and details about the concert environment from these images. They generally show well-attended concerts with well-dressed crowds. The events were typically formal: men wore suits or tuxedos and women evening dresses, gowns, and jewelry. The All University Dances sometimes had decorations, like a western scene with cacti, but often the Union or Gym only received a simple set up. This was different from the fraternity and sorority formals, where elaborate staging (like a Southern plantation themed-party), flowers, and coloration often created a more theatrical atmosphere. In fact, the gym still looked very much like a gym. Its normal purpose never remained very far from view—the crowd stood and danced on a floor still marked by the lines of a basketball court and the backboard and hoop were pushed just to the left or right of the stage.

Bands performed in the Union in a slightly raised nook; in Gregory gym, they typically appeared on a fairly high stage. There was little room between the musicians and the crowd: dancers filled the space all the way up to the band in both spaces. Tables and seats sometimes spilled out onto the dance floor in the Union; other times, the entire wooden floor was used for dancing. In the gym, folding chairs were set up under the balconies, where onlookers sat and watched the orchestras and crowds below.

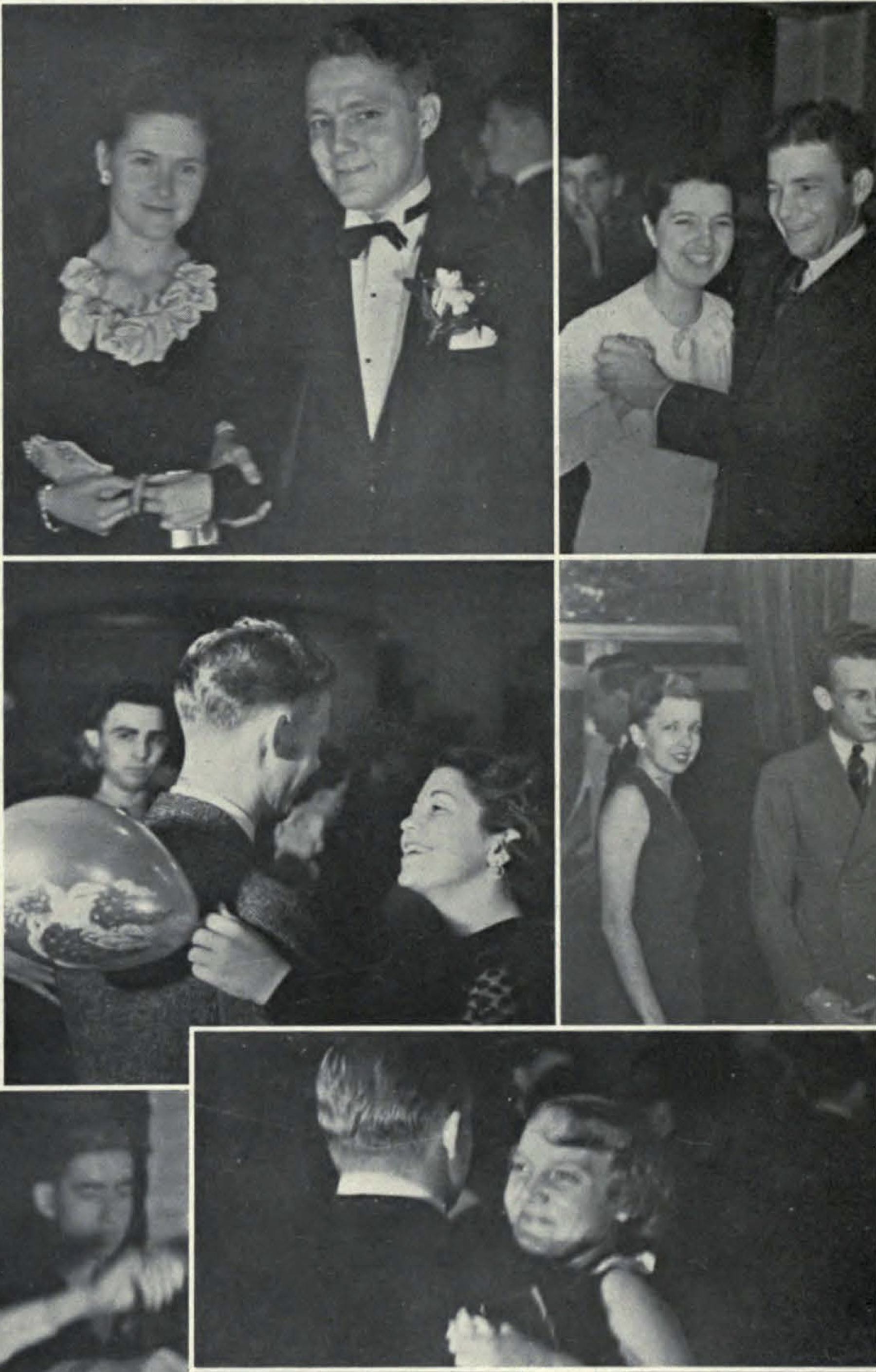

From the the photos, we can see that these were dances, not concerts. Dancers overwhelmingly populated the events, even if some people also stood around or walked through the expansive floor of Gregory. But the student body also had active listeners—members of the audience who paid attention to the musical performance and watched the band, especially at the front by the stage.

This tells us something about how UT students understood popular music at the time: most were interested in it as a vehicle for couple dancing, but there was a small but significant group that also appreciated the arrangements and soloists as an art form or, at least, something that rewarded paying attention to with one’s ears. For others, the dances may have been mostly social events: for seeing friends, going out on dates, talking, and being seen.

Most of the dancing does not seem to have been jitterbugging or swing dancing. The images suggest that most people were doing closed dance steps—with both hands clasped and close body contact—not using the open position of Swing. But there is at least one photo of a couple that is in the middle of a turn and could be jitterbugging. We also know from newspaper descriptions that some swing dancing definitely did occur. It seemed especially popular at UT in the middle of the 1930s.

Possibly the most surprising and (consequently) interesting thing about the photos is how focused they are on the audience, not the orchestras. Many of the famous groups that played at UT do not appear at all in The Cactus. Duke Ellington —already one of the most appreciated bandleaders and composers in American music—played on campus three times in the 1930s and 1940s but there is only one image of his name on the Paramount Theater’s marquee in 1933. And he was not alone. Most of the “name” bands don’t appear at all, including Vincent Lopez (three concerts), Joe Venuti (three concerts), Louis Armstrong (two concerts), Tommy Dorsey (two concerts, one with Frank Sinatra), Glen Gray and the Casa Loma Orchestra (one concert), and Fletcher Henderson (one concert).

The focus on the audiences communicates something about how students thought about the big bands and the dances. All University Dances were mostly about the dancers and students themselves, not the musical personalities on stage. As events, they were about students coming together as a group, seeing themselves together as a large student body, interacting, mixing, dancing together, and having fun. As a whole, “name” bands were mostly about better dancing, not the excitement of seeing a “national” bandleader in person. In this way, All University Dances had something about them in line with the community-orientation of the New Deal Era.

It should be pointed out that this group-centered event was also racially and ethnically homogenous. This communal experience was racially coded as white. Any African American or Mexican American were only welcome on stage, not in the audience.

But there is also some indication that the celebrity culture of the music industry was also growing in Austin. There are still some great action images of famous orchestras performing in Gregory and the Union, including Count Basie , Jimmie Lunceford , Joe Reichman , and Hal Kemp . Photos where bands are the subjects, not the crowds, don’t begin until the very end of the 1930s, however. This may be a sign that the intense promotion of celebrities that began in the mid-1930s started to really sink in to popular consciousness in Central Texas at the end of the decade.