Austin, 1900-1940: Urban Planning, the Hill Country Environment, and Jim Crow Segregation

Austin became a starkly segregated city during the first three decades of the twentieth century. It wasn’t that the color line hadn’t permeated the city before 1900: codes of behavior and violence, coupled with differences in educational and economic opportunity, continued to create a powerful division between blacks and whites after Emancipation. Jim Crow laws began in the last decades of the 19th century. In 1889 and 1891, the state passed laws requiring that whites and black use separate cars when they traveled by train, some of the first gambits in Texas's growing system of legal discrimination.

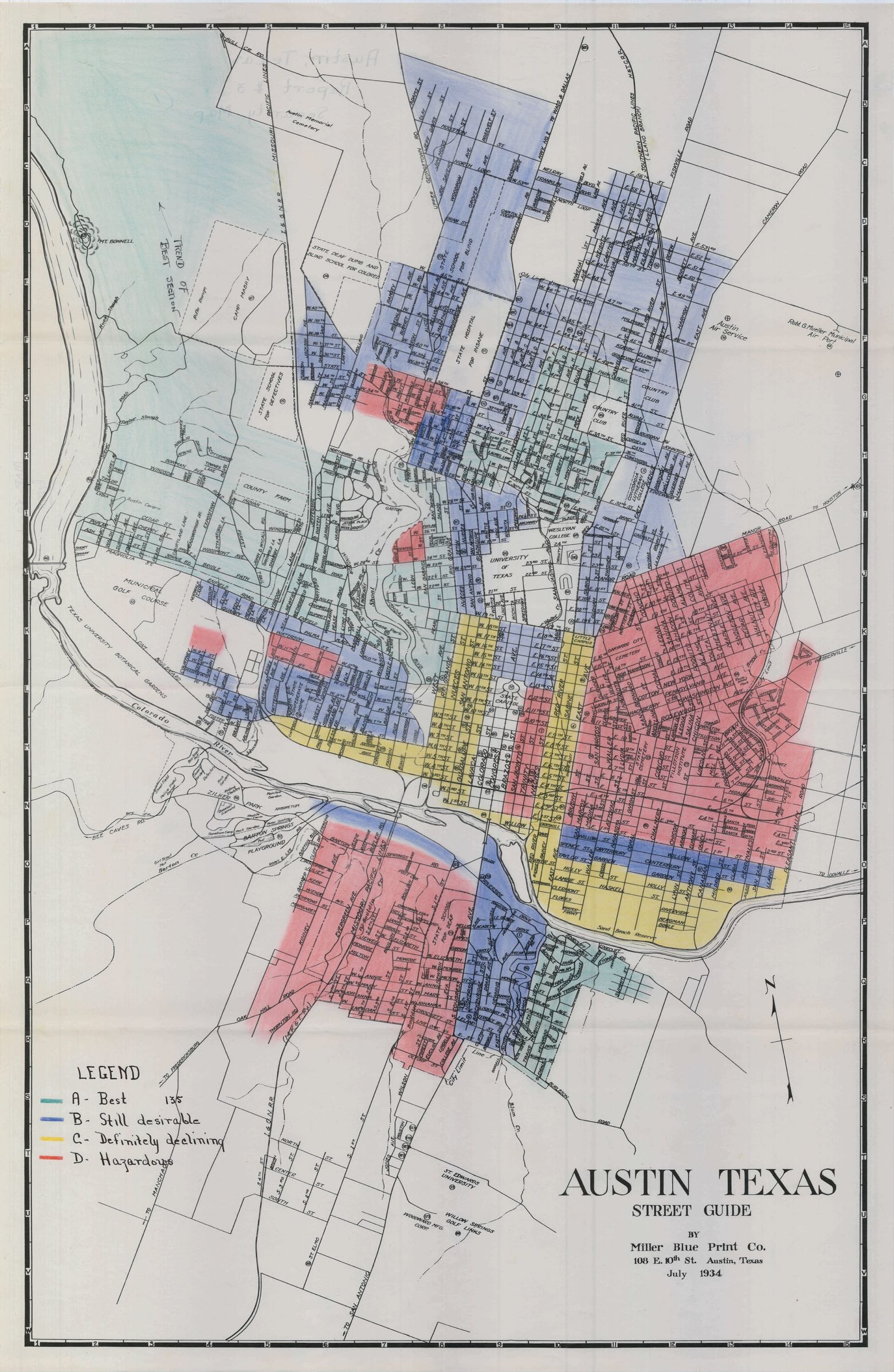

Whites and African Americans still lived next to each other throughout Austin in the late 19th century. There were large freedman communities founded after the abolition of slavery, like Wheatsville and Clarksville, in the western parts of the city, as well as those south of the Colorado River. These were not isolated enclaves. If you look at the maps compiled by the scholar Eliot Tretter, black households were scattered all over the city in the 1880s.

By the 1930s, this was no longer the case. The teens and twenties witnessed an intensification of segregation and political exclusion in Austin. When Duke Ellington visited Austin for the first time in 1933, African Americans—and the growing Mexican American population—lived almost exclusively in the eastern part of city. This occurred as a piece-meal, but deliberate, change in the basic composition of Austin's urban environment. Racial covenants on real estate, the denial of public services, and redlining all worked to push populations of color into the same area beyond the park-filled boundary of East Avenue .

This was a profound transformation of the city. Listen to Andrew Busch, author of City in a Garden, speak extensively about Austin’s urban history, its investment in its arid but beautiful environment, and its history of segregation.