Artist Series

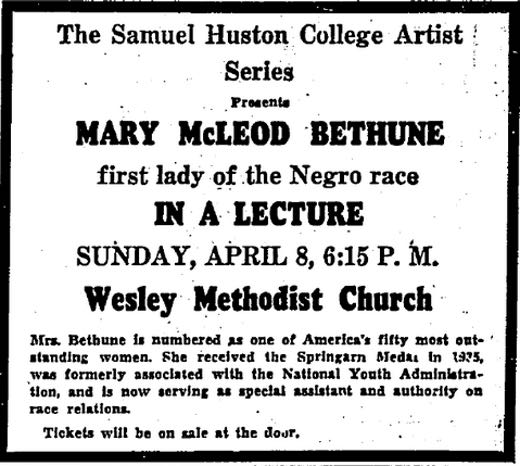

In 1944, Samuel Huston College initiated a short-lived, but significant program devoted to lectures and musical performances. Its “Artist Series,” a collaboration with Wesley Chapel Methodist Church, offered Austin’s wider African American community a longed for venue for intellectual and art music events. It was necessary for these institutions to create an all black event series, since African Americans were excluded from all other classical music concerts and other public talks hosted by the university and the Austin Symphony Society.

The lack of such cultural opportunities was poignant, for Austin was one of the major black intellectual centers in Texas and the Southwest. Although small in size in comparison to Houston or Dallas, the capital had two black colleges. Hoping to offer the wider community opportunities denied to them by the city’s segregated institutions, Samuel Huston created its own space to hear poetry, opera, piano recitals, and political speeches.

The reach and vision of the series was grand and, during its relatively short life, it hosted some of the most important members of the African American intelligentsia in the United States. In its first season alone, it hosted W.E.B. Dubois, Langston Hughes, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and Roland Hayes, all seminar figures in black cultural life. The series soon became a key institution for asserting the intellectual and creative equality of African Americans across Texas. In 1945, it expanded beyond Austin and presented its events in Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, Waco, and Fort Worth as well.

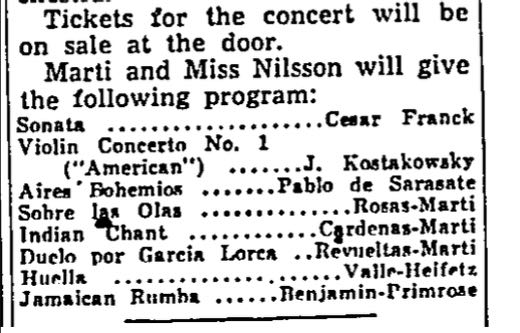

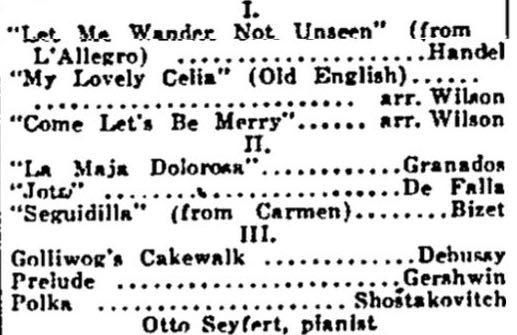

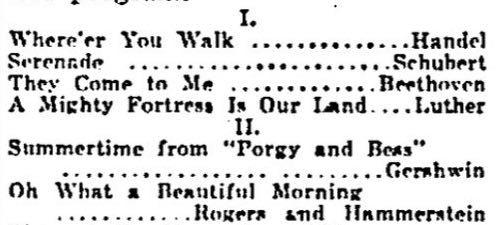

Music

In spite of the weighty significance of her previous appearance before the Lincoln Memorial, Anderson’s concert in UT’s Gregory gym on March 19th, 1945 was before a segregated audience. African Americans who had season tickets to the Artist Series were allowed to attend, but were forced to sit in a separate section on the bleachers. Anderson’s concert was an exception in “high” culture events in Austin at the time. Typically, African Americans were not admitted at all. This was the limited accommodation that the University of Texas in the 1940s was willing to make to the growing voices of the African American community. The stage mirrored the audience: Anderson sang as a guest with the all-white Austin Symphony orchestra, just as blacks remained isolated as visitors amongst Anglo UT students (this was also the case when Anderson appeared in Gregory Gym a second time in 1949).

Many intellectuals and folklorists in the decades around the turn of the century believed that spirituals were the most representative form of African American culture. W.E.B. Dubois, for example, saw them as both the musical embodiment of black experience in the United States—a reflection of the soul of black folk—and the best example of a native American folk form. Dubois characterized them as “the singular heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.”

The presence of spirituals next to pieces by Mozart and Schubert asserted a place for African American music within the Western concert tradition. It declared that African American musical forms—and thus African American performers and audiences—deserved a place in the art music world. Since the late 19th century, many musicologists had argued that classical music demonstrated the superiority of white Europeans; people of color, in their eyes, created a primitive music that betrayed their inherent lack of civilization. White audiences also favored hearing spirituals by black choirs and quartets, but they typically only wanted to hear them next to demeaning plantation songs, not pieces of the Western canon. Concert spirituals, coupled with a song by Schubert or Debussy, were a counter-argument to this claim. They showed that African Americans could not just perform arias and Lieder as well as whites, but could also add significant, unique compositional contributions to the tradition.

Talks

Langston Hughes gave a lecture the week after Dubois. Unlike Dubois, who had traveled to Texas specifically to speak to Huston College, Hughes stopped in Austin on a larger speaking tour throughout the South. Less than a month before, he had delivered an inspired attack on segregation on NBC radio’s debate show “America’s Town Meeting on the Air.” Electrified by the publicity and praise he received, he delivered talks at more than fifty different venues.

A year after his appearance in Austin, he reported on the indignities of travel in the South:

In addition to their own individual statures as intellectuals, the presence of Dubois and Hughes together represented a link between Austin and the larger world of the African American press and letters. Dubois was the long time editor of Crisis, the house journal of the NAACP, and Hughes had begun to write for the Chicago Defender, probably the most important African American newspaper of the time.

Dubois had to pull out at the last moment, however, and instead of Dubois and Rainey, J. Mason Brewer and J. Frank Dobie appeared instead. These two men, both writers and folklorists, represented Austin intellectuals from across the color line. The program focused on the 1944 decision of the Supreme Court to outlaw white primaries, which had been the most effective way that the State of Texas had disenfranchised its black voters. Dobie published an account in the Austin American newspaper after appearing in the first two of the panel’s meetings:

Despite its extraordinary calendar of guests and its rapid expansion in 1945, the Series did not last beyond its third year. After 1946, it ended. The reason was not reported in any of the Austin newspapers.

Notes

- Langston Hughes, “Adventures in Dining,” Chicago Defender, June 2, 1945. ⏎

- Samuel Huston College. Letter from Samuel Huston College to W. E. B. Du Bois, February 20, 1945. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b108-i143. ⏎

- J. Frank Dobie, “Dobie Sees South Thrown Into Days Worse Than in Carpet-Bagging With Moore Bill,” Austin American, March 18, 1945. ⏎